January 31, 2019

The Lesser-Known Bauhaus: Craft and Expressionism in Weimar

Before its association with functionalism and the International Style, the Bauhaus glamorized folk culture and occasionally veered into mysticism.

2019 marks the Bauhaus founding centennial—Metropolis will be publishing articles on the school’s history and legacy throughout the year.

The Bauhaus is often understood as a kind of ex nihilo development in design history, one that pioneered a thoroughly Modernist direction in production. Yet no movement sprouts from nothing: The carriers and transmitters of ideology are themselves conditioned by context. Proponents of the Bauhaus’s archetypal vocabulary—clean geometries, mono-material construction, mass replicability—may be surprised to learn that the school’s early years were characterized by a naturalistic expressionism, individual creativity, and handicraft. These traits were not unique to the nascent Bauhaus; they had coursed through experimental design institutions in Europe for decades prior. The Bauhaus’s early period, in fact, is best seen as bridging the earlier Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements with what has come to be seen as Modernism’s universal visual language.

The Bauhaus was established 100 years ago among the remnants of the Grand Ducal Saxon Academy for Arts and Crafts in Weimar, Germany. “It was taking over not only the buildings but the legacy,” notes Barry Bergdoll, professor of art history at Columbia University and former architecture and design curator at MoMA, which staged a sweeping retrospective in 2009. The School of Arts and Crafts had been founded by designer Henry van de Velde, whose Jugendstil leanings gave it a distinct Art Nouveau flavor. After the outbreak of World War I, van de Velde—a foreign national—was forcibly repatriated to his native Belgium, and recommended a young, battle-seasoned Walter Gropius as his successor. Bringing both horrific memories from the Western front and a body of design experience from the Deutscher Werkbund and Peter Behrens’s firm, Gropius sought to forge a “spiritual renewal of humanity,” Bergdoll explains. Given the recent war and acute economic hardship, the early Bauhaus was “seeking to rebuild a more communitarian-based society” and establish “new beginnings in different and conflicting ideas and personalities,” Bergdoll says.

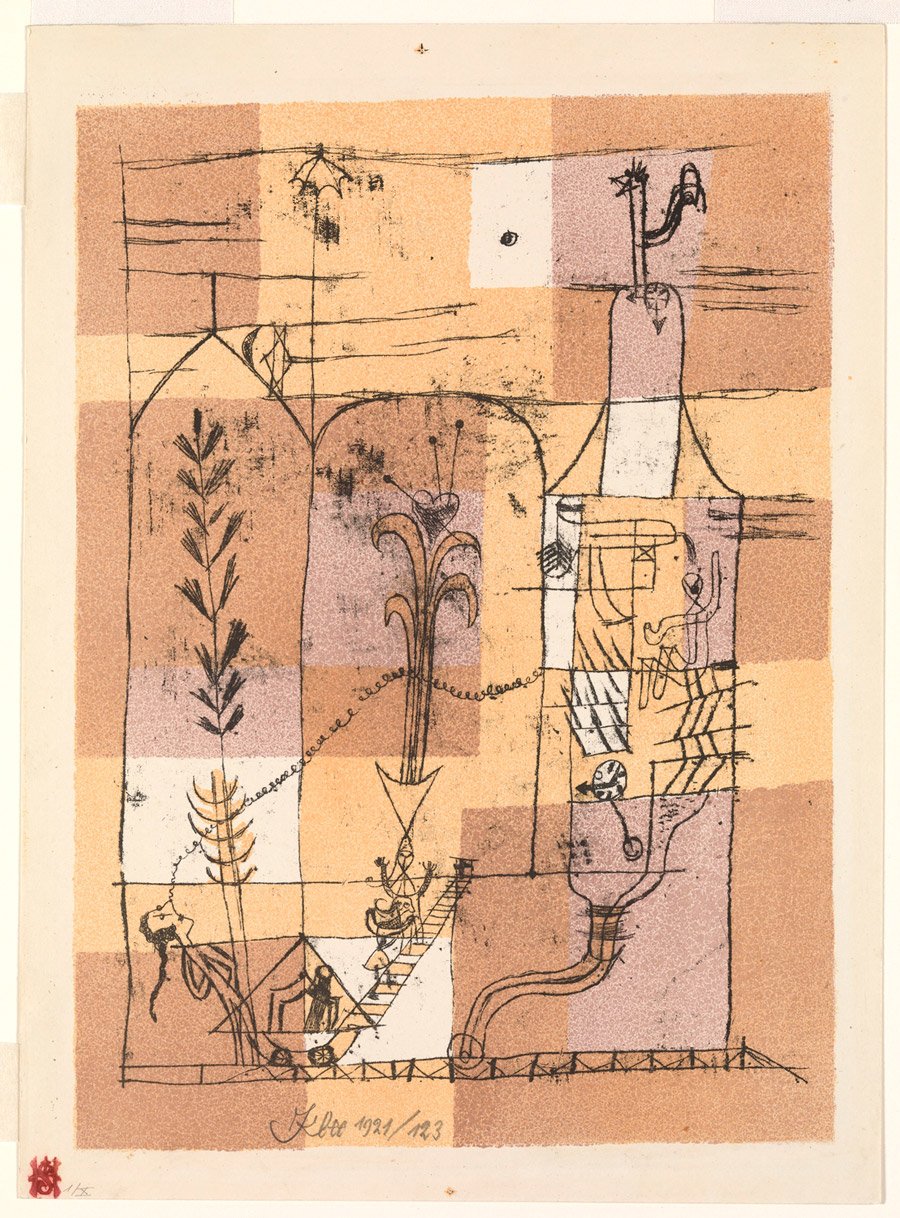

Stylistically, the trauma of industrialized warfare tempered the Continent’s infatuation with technology, sparking a return to more naive means of production and an emphasis on the expressionistic. For the first Bauhauslers, this expressionism occasionally veered toward mysticism, evident in the Zoroastrianism of preliminary course teacher Johannes Itten. His works, along with those of Wassily Kandinsky and other Bauhaus masters in Weimar, testify to the highly individualized and eclectic atmosphere in the early years. (Itten’s growing allure among students sat uneasily with Gropius, who replaced him in 1923 with László Moholy-Nagy.) Paul Klee, who taught in the bookbinding and mural painting workshops, brought a distinct interest in expressionist art movements such as Cubism and Surrealism. Even Gropius, the hard-edged formalist, dabbled in expressionism; his Monument to the March Dead in Weimar is an abstracted, thunderbolt-like concrete form.

Concurrent with this focus, many of the Bauhaus’s early works glamorized country life and folk culture, what Bergdoll refers to as a “romantic celebration of the innocent peasant,” unburdened by academic discourse or political whims. Much of the output of the weaving and (short-lived) pottery workshops references historical artistic movements and means of production, perhaps a nod to socialism or populism. The African Chair—by an 18-year-old Marcel Breuer and master weaver Gunta Stölzl—evinces preindustrial techniques and material preferences and betrays an uncharacteristically colonial cultural gaze.

It was only in later years, with the memory of machine warfare fading and economic conditions stabilizing, that Gropius repositioned the Bauhaus manifesto from a unification of the arts through craft to an explicit desire to “reestablish the artist’s lost contact with the world of production,” an overture to the Bauhaus’s subsequent development. This return to the promise of Modernism culminated in the well-attended 1923 exhibition in Weimar at the Haus am Horn—designed as both the presentation’s largest object and its venue. The show displayed the school’s then-radical furniture and housewares and was meant to assuage state “pressure placed on Gropius to demonstrate what the Bauhaus had been up to,” says Joachim Homann, who is curating an exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art to celebrate the centennial. Although handmade, the pieces suggested replicability and debuted the signature tricolor palette, helping crystallize “how the modern style we’ve come to associate with the Bauhaus was forged.”

During the school’s early years, traditional and proto-Modern materials and techniques were combined in often-surprising— and prescient—ways. The African Chair and the Sommerfeld House in Berlin (1921 and 1922, respectively) bear out this tension: Both are expressionistic in design, yet their precut wood constructions display an engagement with prefabrication. Gropius’s F51 armchair (1923) and other pieces in his director’s office also encapsulate this relationship between craft and functionalism, and anticipate more rigid, linear geometries. For Anke Blümm, curator at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, which oversees the city’s cultural heritage, Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s now-ubiquitous lamp also exemplifies this aesthetic dialectic: “It seems like an industrial product,” she says, “but at that time, in 1924, it was still a handmade prototype.”

Gropius’s recentering of the school’s objective toward creating prototypes for a mass market—“to get money for his always-underfunded institution,” Blümm points out—undeniably changed its development. The Bauhaus’s early expressionism incrementally gave way to emphases on rationalism and functionalism more in line with consumer culture and what would become known as the International Style. In 1924, the Thuringian regional government, exasperated by the avant-garde whippersnappers roaming what continues to be a conservative city, withdrew its financial support. By early spring in 1925, the Bauhaus in Weimar lay all but shuttered, its masters and students displaced to the industrial city of Dessau, where a gleaming, neatly framed school building awaited.

You may also enjoy “The Eerie-Fantastic Interiors of Friedman Benda’s Blow-Up.”