December 22, 2021

A New Concept for Good Architecture: Embodied Justice

While the green building movement has had success limiting dangerous toxins in products, few companies have enough information about their own suppliers. And materials can pose threats throughout their supply chain. For instance, while many plastic products are less toxic in their final form, they can pollute air and groundwater in the places where they’re produced.

“When we think about material health, we have to think: ‘Whose health are we protecting?’,” says Jane Abernethy, Humanscale’s chief sustainability officer.

Over time new standards—now only in their initial phases—could help identify and quantify the industry’s upstream and downstream ramifications. As with embodied carbon emissions, we could soon be able to measure the amount of embodied justice (or injustice) in our designs.

MATERIALS: TOXIC COSTS

One of the earliest drivers of sustainable design was a growing awareness of how metals like lead, chemicals like formaldehyde, and volatile organic compounds common in building products contributed to health problems for occupants. The green building movement has since had considerable success limiting these and other dangerous toxins. But it continues to bump up against our country’s entrenched social realities, not to mention its own significant blind spots.

For instance, in the 1990s the movement took aim at vinyl and PVC: cheap, omnipresent materials harmful for their use of chlorine in manufacturing and the presence of phthalate plasticizing compounds—known toxins that leached out of vinyl flooring and wall products.

However, when less-toxic plasticizers were discovered and phthalate-free vinyl products were introduced, the green building movement took the pressure off. Nothing was done about the chlorine, which, though it does not off-gas or have an effect on buildings’ interior air quality, has had devastating effects on the places where vinyl is produced. For example, it still pollutes groundwater and air in places like “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana, our nation’s chemical hub, where a majority Black population bears the health and environmental costs of our fossil fuel–based economy.

Today vinyl products are again commonplace, even in the most sustainably constructed buildings that boast LEED and WELL certifications.

“The green building movement has succeeded in protecting our occupants, but at the expense of fence line communities around the world and especially in the United States,” explains Bill Walsh, founder and strategic adviser of the Healthy Building Network, a nonprofit that, among other things, checks common building materials against a set of sometimes overlapping lists of chemicals of concern.

As designers and specifiers begin drawing connections between design products and the communities impacted by their manufacture, some brands are starting to step up. Office furniture manufacturer Humanscale, for example, has ramped up its efforts in supply chain transparency. In its case, understanding the chain’s complexity and opacity grew out of its work on healthy materials.

“If you look at just the product as it sits at one moment in time, that’s not how it lives through the whole life cycle,” explains Jane Abernethy, the brand’s chief sustainability officer. “There’s all the production that leads up to it. There’s delivery on-site, there’s the folks who are using it, there’s the folks who are cleaning it, there’s the folks who will disassemble or deal with it afterwards. So, when we think about material health, we have to think: ‘Whose health are we protecting?’”

Abernethy has led an effort to redesign her brand’s products to eliminate materials that are potentially harmful not only to end users, but to people in and around manufacturing and recycling facilities across the globe. It can be a difficult conversation to even start with suppliers, she explains, pointing out that they may be worried about being cut out of the loop on purchasing agreements, losing business, or finding themselves in legal trouble. But the more questions buyers ask, the more transparency becomes the norm in the industry, she says.

Abernethy points to Chromium (VI), also known as hexavalent chromium, which is highly toxic in a manufacturing setting. Humanscale wanted to replace it with nontoxic Chromium (III) on one part of its Liberty Task Chair.

“[Chromium (III)] is harder to process, and it’s not the default, so there’s not much of a market for it,” she recalls. “What we had to do was convince our supplier that they should move to that.” The supplier had to purchase new equipment and reconfigure its factory, but the benefits went beyond Humanscale’s products.

“When we start to ask for these things to change, it causes ripple effects and bigger changes, especially when we’re looking at mass production, where the decisions get repeated many, many thousands of times, possibly every year,” she says.

FORCED LABOR

Unfortunately, in the tangled web of a global supply chain, few companies have as much knowledge about their suppliers as Abernethy and her team. And toxicity is not the only concern. The global building industry, and many of the industries that supply it with raw materials, such as mining, logging, and textiles, are rife with forced labor and what some describe as modern-day slavery. These injustices are so prevalent that a publication of the International Labour Organization, Global Estimates of Modern Slavery, has ranked the construction industry as the second biggest culprit in the continuation of forced labor after only the domestic-service sector.

Another study, Design for Freedom, published by the nonprofit organization Grace Farms in support of its initiative of the same name, identifies 12 building materials that are at high risk of being produced by forced labor. They include rubber, glass, fiber and textiles, steel, electronics, bricks, timber, stone, copper, iron, minerals, and precursors, the last of which is a catchall term for the compounds and materials used in manufacturing and industrial processes.

But behind these broad categories, there are specific—and heartbreaking—material histories that illuminate the ways in which our opaque and convoluted supply chains hide even the most brutal forms of injustice.

For instance, mica, which is used in processing steel, is mined chiefly in India and Madagascar, where young children are forced to work the mines, because their small bodies and hands are valued in cramped conditions and due to a lack of technological innovation.

Forced labor is rampant throughout the global construction industry. Seemingly harmless materials can have harmful supply chains. For instance mica, which is used in processing steel, is mined chiefly in India and Madagascar, where young children are forced to work the mines.

Closer to home, undocumented workers are commonly mistreated and underpaid on construction sites. What responsibility do architects and designers have to the people who bring their designs to life?

Sharon Prince, CEO and founder of Grace Farms Foundation, also relates the complex story of polycrystalline silicon, a key ingredient in the manufacture of photovoltaic solar panels, which of course are an urgently needed source of green energy. Eighty-five percent of the global supply of this mineral comes from China, she notes, and of that, 45 percent comes from the Uyghur region, where human rights abuses are known to abound.

Forced labor, she says, has kept the price of polycrystalline silicon artificially low, preventing innovation in photovoltaic technology. Now that silicon prices are rising as a result of the coronavirus and the threat of the proposed Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (which if passed would limit U.S. imports of certain products from Western China), we have few alternative technologies at hand, limiting our ability to generate clean power.

ARE ARCHITECTS AND DESIGNERS COMPLICIT?

So how are architects and designers responsible for this mess? Historically, the design field has rejected any notion that its practitioners might be responsible for the ethical practices of builders and product suppliers. But some are arguing that their position as mere service providers must change and that architects and designers have more leverage than they may realize.

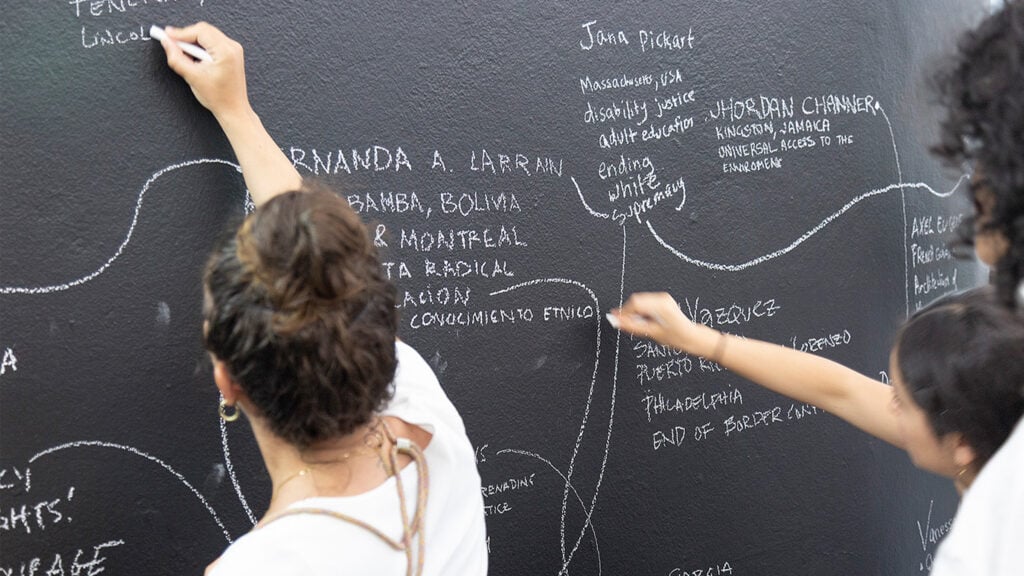

One such group is The Architecture Lobby, which describes itself as “an organization of architectural workers advocating for the value of architecture in the general public and for architectural work within the discipline.” Its campaigns and working groups have been at the center of conversations about architects’ role in the human elements of design.

“We demand … that architects think about their role in spatial justice differently…. We should be in the process of choosing what is going to get built as opposed to just designing what somebody else has preprogrammed,” says Peggy Deamer, a professor emerita at Yale University’s School of Architecture and founding member of the lobby.

Another group of practitioners challenging their peers is Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?), which came together in response to revelations of unjust labor conditions experienced by construction workers in the Persian Gulf. Buildings by internationally renowned architects were being constructed by migrant laborers toiling in unsafe living and working conditions, with few legal protections, for too little pay.

“When we first started, we went to our colleagues and their practices and asked, ‘Would you sign this pledge around exploitation of construction labor?’ And the immediate response was ‘We have nothing to do with that. That’s the contractor side…. We don’t deal with that labor,’” recalls Mabel O. Wilson, professor of architecture at Columbia University and a founding member of WBYA?

The group asked a simple question—“Who builds your architecture?”—and convened a series of workshops that brought human rights experts, anthropologists, artists, and architects together to

look into the mundane realities of large construction sites. It thus unearthed complex networks of labor brokers, global migration, remittances, shoddy worker housing, and human rights viola-tions—on which cutting-edge international architecture often depends.

The Critical Field Guide the group published in 2017 points out several ways architects can help dismantle these global systems and start to make their projects less exploitative. This includes supporting workers’ ability to demand better conditions, relabeling “workers camps” as “worker housing,” and treating workers as stakeholders rather than tools.

There are few incentives for architects to devote this kind of real attention to jobsite conditions. The AIA’s code of ethics doesn’t have anything specific to say about it, and LEED offers only one pilot credit for “social equity within the project team.” But there are signs of change.

MEASURING EMBODIED (IN)JUSTICE

Architects, even as agents of a developer or property owner, have a lot of discretion as to how budgets are allotted. But without a way to calculate the social harms of certain materials, and quantify the social costs of construction, it’s difficult to convince them of their accountability in a project’s overall embodied justice.

“Maybe we need to develop a kind of social justice scoring system,” says Dayton Schroeter, a design director at SmithGroup’s Washington, D.C., office. He suggests that designers need access to standards and protocols for design justice, similar to the way standards have been developed for accessibility and sustainability.

Such standards are beginning to emerge. The International Organization for Standardization offers ISO 26000, a global framework for social responsibility that, while not linked to a certification, provides a universal language for assessing social impact, including in transnational projects. Likewise, Health Product Declarations, already a mainstay of green building verifications, are crucial for determining the hidden impact of a product or material, listing chemicals (including those that are not tightly regulated) that may have adverse health impacts on producers or consumers.

The U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED, the most widely recognized green building certification, also offers a few certifying credits for social equity considerations, including one pilot credit for “Social Equity in the Supply Chain,” which encourages designers to assess the business practices of their suppliers. Likewise, WELL has taken on initiatives to promote wellness-oriented design and improved indoor air quality in affordable housing and disadvantaged public schools, where unsafe materials have historically contributed to higher rates of asthma and other health conditions—part of the toxic legacy of government disinvestment and redlining.

As the conversation about designing for equity progresses, architects, clients, and activists are beginning to demand clear frameworks for evaluating the social damage—or social good—done by a project. Several organizations are taking inspiration from the ratings systems and transparency protocols brought about by the green building movement, which over the last 30 years has transformed how we evaluate the environmental impact of design.

“There’s more we can do to push the industry on these questions of what we build,” says Lindsay Baker, CEO of the International Living Future Institute.

So far, the Just Label from ILFI, launched in 2014 (and updated as Just 2.0 in 2019), offers the most comprehensive model for assessing a firm’s or manufacturer’s commitment to equity and social justice within its own staff. It’s based on principles like diverse hiring, pay equity and transparency, and social engagement. However, it does not extend to a firm’s projects or a manufacturer’s products.

Lindsay Baker, CEO of ILFI, says the Just Label’s limitation is intentional, making it applicable to any business, not just architecture and construction. However, building owners seeking Living Building Challenge certification (which is separate from the Just Label) must source at least 20 percent of their materials within 300 miles of their project, and that project must be free of Red List chemicals of concern, such as PVC.

“I would say that there’s more we can do to push the industry on these questions of what we build,” says Baker, indicating that while the architecture and design industry may be new to conversations about vetting clients’ and suppliers’ ethics, it already has models for doing so in areas such as finance and insurance, which are commonly applied. “There’s a lot of precedent out there for [firms] to say, ‘There’s a certain set of companies we don’t do business with because of our morals or our values,’” she says.

THE GREEN BUILDING MOVEMENT’S NEXT CHALLENGE

Practioners who have brought green building practices from the margins to the mainstream could be that critical first wave of embodied-justice policy adopters who revolutionize how architects and designers build and specify.

Can we establish a way to calculate a project’s or product’s embodied injustice? Can we tally up the impact—positive and negative—on the human beings and communities its creation has touched? It’s a radical idea and one that goes against the prevailing mores of an industry in which building materials are anonymous commodities divorced from their social histories and where labor and design are often siloed.

Mabel O. Wilson points out that the struggle to undo the social damage of a globalized, capitalized supply chain is directly related to the struggle to slow climate change. As a result of the pandemic, she says, “I think people now are aware of how exploited they were as workers. I think people have finally just said, ‘We’re done. We’re not going back to that place that doesn’t account for our lives.’ It makes the owners incredibly wealthy, but it doesn’t account for how we live, and it’s destroying the planet we inhabit.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.