July 24, 2020

Hitler’s Northern Utopia: Building the New Order in Occupied Norway

In her new book, Despina Stratigakos tells the story of how Nazi architects and planners began to build a Nordic empire in Norway during World War II.

Between 1940 and 1945, German occupiers transformed Norway into a vast construction zone. This remarkable building campaign, largely unknown today, was designed to extend the Greater German Reich beyond the Arctic Circle and turn the Scandinavian country into a racial utopia. From ideal new cities to a scenic superhighway stretching from Berlin to northern Norway, plans to remake the country into a model “Aryan” society fired the imaginations of Hitler, his architect Albert Speer, and other Nazi leaders. In Hitler’s Northern Utopia, Despina Stratigakos provides the first major history of Nazi efforts to build a Nordic empire—one that they believed would improve their genetic stock and confirm their destiny as a new order of Vikings.

Drawing on extraordinary unpublished diaries, photographs, and maps, as well as newspapers from the period, Hitler’s Northern Utopia tells the story of a broad range of completed and unrealized architectural and infrastructure projects far beyond the well-known German military defenses built on Norway’s Atlantic coast. These ventures included maternity centers, cultural and recreational facilities for German soldiers, and a plan to create quintessential National Socialist communities out of twenty-three towns damaged in the German invasion, an overhaul Norwegian architects were expected to lead. The most ambitious scheme—a German cultural capital and naval base near Trondheim—remained a closely guarded secret for fear of provoking Norwegian resistance.

The following is an excerpt from HITLER’S NORTHERN UTOPIA: Building the New Order in Occupied Norway by Despina Stratigakos. Copyright © 2020 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

In shaping his German city on the fjord, Hitler planned to leave his mark above all in its cultural brilliance. As [Albert] Speer reported to [Reichskommissar for Norway Josef] Terboven in August 1940, in the early stages of the project, Hitler told him that what he had in mind was “the creation of the northernmost cultural center of the Greater German Reich.” Nothing would be lacking. “According to [Hitler], the new city should have everything necessary for a city of cultural importance, such as an opera, theater, library building, and grand picture gallery, but also a stadium, swimming pools, and so forth.” The lavishness of Hitler’s vision would certainly have played a role in Speer’s determination to build the city, not to mention the Führer’s obvious enthusiasm for the project. In a late-night monologue on January 15, 1942, at his Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia, Hitler stated that he wanted to act as the new city’s patron, referring, it seems, to a special role as cultural benefactor.

Although we have few details about the cultural institutions Hitler planned for the new city, the national focus is clear enough. On February 19, 1942, in another late-night talk at his headquarters, Hitler announced that the grand picture gallery—the collections for which he himself would assemble—would be dedicated “solely to German masters.” Hitler believed that art not only expressed but also served to realize a nation’s cultural and political greatness. It is no coincidence that the first monumental building he commissioned after coming to power was the House of German Art in Munich, an art gallery devoted solely to contemporary German artists and to defining a new artistic vision and standard for the Third Reich. Hitler’s proposal to open a German art gallery in the northern reaches of the empire was thus a significant gesture, suggesting how he envisioned reinforcing the cultural identity and strength of Germans living outside the nation’s traditional borders. At the same time, he also saw such projects as his greatest legacy. Referring to his Trondheim plans, he stated, “Wars come and go; only the works of human culture remain.”

This emphasis on the new city as an artistic and cultural beacon as well as Hitler’s desire to act as its patron strongly suggests that he imagined it as a Führerstadt, or “Führer city,” in the North. Before the war Hitler had designated five such cities—Berlin, Hamburg, Nuremberg, Munich, and Linz—which were to be transformed into the architectural and cultural jewels of the Third Reich. Plans for their reconstruction entailed the massive reorganization of their urban centers to accommodate monumental new structures and cultural institutions. Hitler intended to endow his hometown of Linz, for example, with an immense art gallery displaying the very best collections of European art (much of it confiscated from other countries), which he himself would curate. The new city planned for the Trondheim Fjord, if designated a Führer city, would have been the first such urban “jewel” outside the boundaries of the Greater German Reich as they had existed before 1939. Moreover, it would have been the first one to be created whole cloth, unconfined by previous urban settlement.

Hitler’s proposed art gallery for the new city on the Trondheim Fjord would have joined another major cultural project that similarly would have proclaimed the new settlement’s German roots: a monumental war cemetery and memorial (fig. 5.3). This idea originated with the Army High Command Norway, which in early 1941 proposed war cemeteries for four Norwegian towns: Bergen, Narvik, Oslo, and Trondheim. Together, they were to hold thirty-one hundred German soldiers’ graves. Three of these locations were associated with casualties and fighting that occurred during the invasion: the sinking of the Blücher, in the Oslo Fjord, and of the Königsberg, in Bergen, which had resulted in significant German losses, and the dogged resistance of General Eduard Dietl’s mountain troops in Narvik, which had elevated the town to heroic status. The lure of Trondheim, by contrast, seems to have been its future importance as a naval base.

Wilhelm Kreis served as the architect of these projects, which were part of a larger mission to honor Germany’s fallen soldiers in the newly occupied war zones throughout Europe. In March 1941, and at Speer’s suggestion, Hitler named Kreis general architect for the design of German war cemeteries. Kreis’s career underwent a remarkable reversal during the Third Reich. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he had been dismissed as president of the Association of German Architects. Speer’s patronage revived his career with high-profile commissions, such as a monumental Soldiers’ Hall in Berlin—a National Socialist appropriation of the Norse Valhalla, a majestic hall ruled by the god Odin and inhabited by worthy dead warriors. Speer considered Kreis, who was nearly twice his age, a close friend and had previously traveled with him to Italy. Speer invited him along on his 1941 trip to Norway; when this was canceled, Kreis traveled by himself, in August 1942, to scout locations for his war cemeteries.

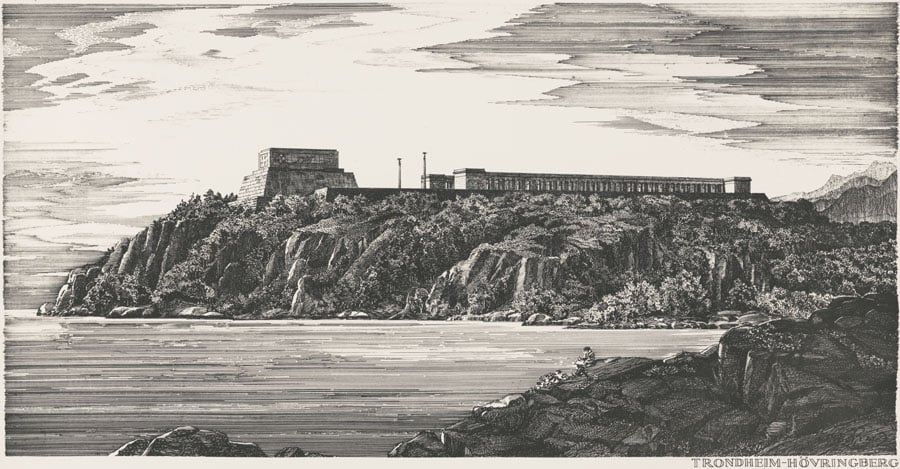

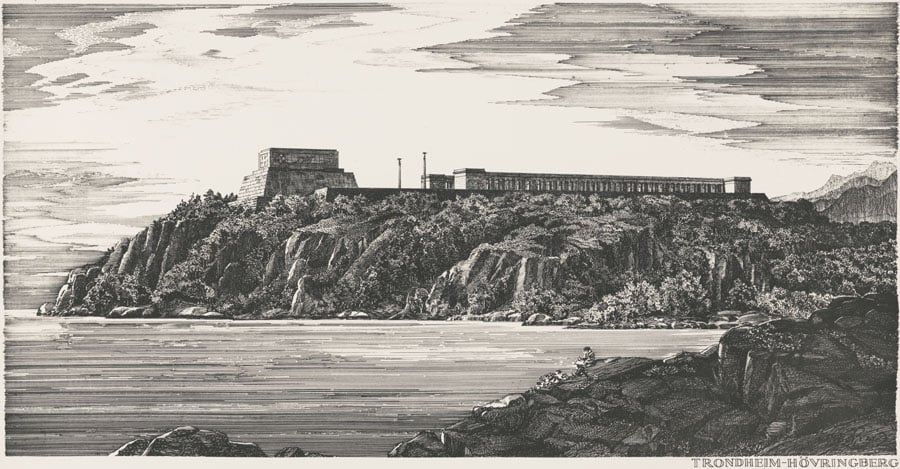

In Trondheim, Kreis’s attention focused on Høvringberget, a 230- meter-high mountain in Bymarka overlooking the fjord, on the peninsula Hitler had chosen for the new settlement. In this location, the stone monument he designed, with its large, engraved swastika, would have been highly visible from the sea, announcing the new German colony to approaching visitors (fig. 5.3). Like his other cemetery designs, which were inspired by the Castel del Monte in Italy and the Athenian Acropolis in Greece, it was intended for an elevated location. The memorial would have made a dramatic destination for German residents out for a nature walk, a place from which they could survey their new lands from the vantage of the German soldiers who had died to acquire them. It would have powerfully connected the new city’s residents to a “heroic” point of German origin, reinforcing a deep bond to blood and nation. The design was widely published, including in Das Reich, a successful weekly newspaper with a European focus launched in 1940 by Goebbels, and in Die Baukunst, the National Socialist architecture journal edited by Speer.

The cults of art and death were integral, intertwined elements in the National Socialist Weltanschauung. In anthems, theater performances, art exhibitions, memorials, ceremonies, and processions, the fallen comrade was symbolically and collectively lamented and exalted. When the Nazis expanded their empire, they exported their myths and rituals to their new territorial possessions. But they did not elevate them to the same degree of visibility everywhere. The prestige projects envisioned for the new German city on the fjord suggest that Trondheim had a special status for the Nazis, which led Hitler to see it as a worthy place to build the northern cultural capital of his Greater German Reich.

National Socialist writings about Trondheim make clear its many positive associations for German propagandists. Foremost among them were Trondheim’s Viking origins, recorded in the Icelandic sagas, and its status as the capital of powerful kings who, in the late Viking period and early Middle Ages, unified a vast northern empire. The monumental stone architecture of the Nidaros Cathedral, the medieval church in which Norwegian kings were crowned, also impressed. German writers similarly admired Trondheim’s traditional wooden architecture as well as the generous public spaces of its baroque urban plan, laid out by Johan Caspar von Cicignon after the catastrophic fire of 1681. Finally, German propagandists sought out traces of German influence in Trondheim, from wealthy merchants and bankers to architects, who (they claimed) had indelibly shaped the town’s development.

Trondheim’s positive features were often contrasted in National Socialist propaganda with Oslo’s purported flaws. Where Trondheim was ancient and haunted by the ghosts of warrior kings, Oslo was considered modern and soulless. Despite its German traces, Trondheim was lauded as the most Norwegian city in the country, rooted to the people and the soil; Oslo, on the other hand, was “American-unauthentic.” Trondheim’s architectural beauty and open urban spaces put Oslo’s functionalist buildings and crowded, working-class neighborhoods to shame. Although Oslo had emerged in modern times as Norway’s political capital thanks to its geographical location, Trondheim had the feel of an imperial capital based on its role through the ages as a spiritual and cultural center.

These accolades penned by National Socialist writers raise questions as to why the German occupiers did not choose to rebuild the existing town of Trondheim as their own settlement. The reasons are both practical and symbolic. The scale of the planned naval base was ill-suited to Trondheim Bay, which was limited by size and geological instabilities. From a symbolic perspective, Trondheim’s strong sense of Norwegian-ness would have impeded the superimposition of a new German identity. Indeed, such an attempt would have risked the reverse: the Norwegification of the German settlers, a form of cultural “degeneration” that—as seen with regard to soldiers’ homes—worried the occupiers. Significantly, there is no evidence that the Nazis saw the establishment of a new city as an opportunity to develop shared ground, as a people, with the Norwegians. To the contrary, the settlement was envisioned as a place apart, a German enclave that remained separate from the surrounding native Norwegian population. Positive associations with Trondheim were to be assimilated into a carefully defended web of German culture, on German terms.

You may also enjoy “Karen Braitmayer, Founder of Studio Pacifica, Weighs in on Accessible Design“

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.