February 14, 2023

How Can Architecture Create and Preserve Black Spaces?

Kelly Beamon: Congratulations on your new role. I know you’ve been involved with the Center for Architecture for years, participating in its Learning By Design program as a teen and later contributing to it as a professional. You attended meetings of NYCOBA/NOMA (the local chapter of the National Organization of Minority Architects) in its space. What’s your plan for strengthening the CFA’s mission?

Peter Robinson: The outgoing executive director Ben Prosky and I spoke about wanting to advance our mission to be more impactful in communities across New York City. I have already begun working with our Interim Executive Director Jesse Lazar and our CFA President Jennifer Sage on this. I feel, to some extent, that our Learning By Design program, led by Catherine Teegarden here at CFA was doing that. Through it, we’ve trusted that the programs we share with children will somehow translate to their families. But we have only this fragile connection through the students. So we now want to work through ways that we can be directly involved with communities, with families.

KB: Is that programming set now?

PR: No, we’re just starting that process, which for me, involves recognizing black spaces, around which many students’ families live.

Recognizing Racialized Spaces

KB: Right. You’ve spoken about ways that spaces are racialized. Why is it important to acknowledge and preserve such spaces if they aren’t otherwise designated by mainstream architectural organizations?

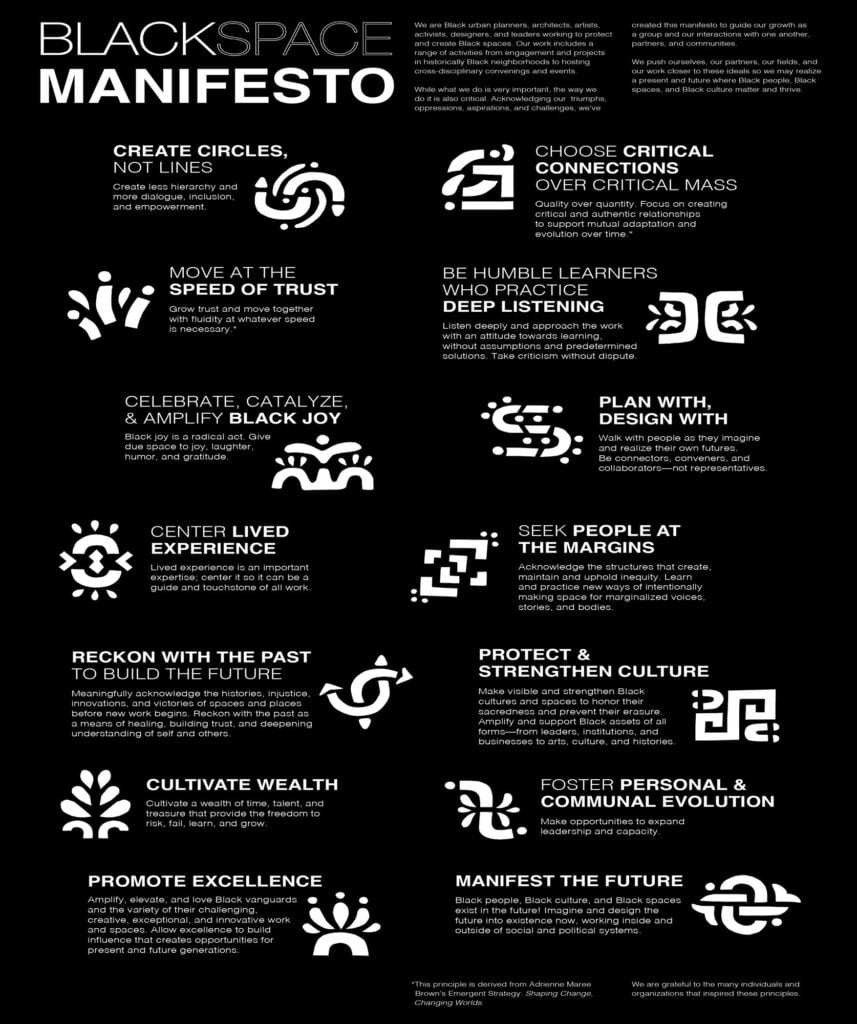

PR: One clear way to consider [ways that space is racialized] in the realm of practice is collaboratively. I’m one of the founding members of BlackSpace Urbanist Collective. We have convened as a group of architects, urban planners, artists, and urbanists who think about what it means to critically regard black space and our [professional] roles in them.

It was founded with a vision that ‘demands a present and future where Black people, Black spaces and Black culture matter and thrive.’ We gathered with an understanding that racialized space. What would we bring in terms of our professionalism and shared experiences to that conversation? BlackSpace was really born out of that kind of inquiry.

KB: So these are questions you were already exploring individually?

PR: I was already examining projects through that lens most of my career and throughout most of my academic training.

I was lucky that I had the opportunity to think about space as a racialized condition. Born in Jamaica, and raised both there and in the United States, I had the benefit of a dual point of view. And I was given the chance during my academic training to think about that. For my undergraduate thesis (a market for downtown Kingston, Jamaica—a black city in a black country) there was an awesome amount of support for considering racialized space and wanting to push for ways that architecture could respond to it. I didn’t frame it like that. But I felt motivated to make inquiries into that sort of provocation, to navigate how the built environment could respond and what was already perceived as a racialized space.

Ultimately, my thesis was to encourage the free flow of a market by thinking about which devices or utilities of architecture were promoting a kind of racialized life. And I used that term very specifically: I was looking keenly at the poetry of Louise Bennett, a very famous Jamaican poet and folklorist, whose work speaks descriptively about Jamaican life and uses Jamaican language. She talks about market life, country life, life in the city. She talks about life in the diaspora. And I thought of all of that: How do you bring that kind of thinking into an undergraduate thesis of architecture?

Embracing that sort of intellectual space was almost required of us as undergraduates at Cornell, to broaden the discourse of architecture. . .and allow for other sets of information to inform the rigor of how we conceived and considered architecture.

KB: Did you see that as a rare privilege? Being afforded time to regard the social impact of architecture that way?

PR: I was at Cornell at a very privileged time, in the early ’90s, and we had a lot of black and brown peer support infrastructures. We had our own Minority Organization of Architecture Art and Planning (MOAAP) and we got support to attend the NOMA conference every year. We built comrade-ship with folks who were asking similar questions and very much putting this idea of what it means to be racialized or black specifically at the forefront. Even as early as high school, I was thinking about architecture as a way to represent and ask deep questions.

KB: College enhanced that?

PR: Yeah, because suddenly you were clearly other, right? And that was the first time you were like, ‘Oh wait, architecture could start to maybe engage these other questions.’

KB: Was it a challenge to extend that thinking in a real-world practice?

PR: I brought all of that into practice with me immediately in my firm WorkUrban.

Engaging Students in Design at the Weeksville Heritage Center

KB: You’ve since developed a process for clarifying the method of inquiry you began as a Cornell student addressing racialized spaces. Would you please touch on your current projects that use this approach?

PR: All right. So we can talk about the reception desk at Weeksville Heritage Center, which is a project that I’m working on with My Brother’s Keeper (MBK) students in New York City. I was invited to design a reception desk by Ray Coddington, a director of Weeksville. And I asked him, “Can I do it with high school youth?”

I’ve been working with MBK since 2020 to help introduce young people to the [process of designing] the built environment and ways they can understand the history of racialized spaces in their communities and be conscious of the fact that they’re also making them.

We have open and transparent conversations about blackness and what it means to create something for and with the black community. And not all of our students are black. But [with this process] there is the ability to have that conversation.

KB: That’s a process that makes some established architects uncomfortable. How is it for high school students?

PR: It is really awesome. People tend to ask, ‘Well, can you have this conversation so broadly?’ And I respond ‘We’re having it with high school kids and they’re thriving in the process.’

We ended the summer program by building a design strategy report on what the Weeksville desk could be. To inform that, we’d met with architects, including Dr. Sharon Sutton, who shared her work, which was on view at the CFA in the Reset Show and centered on her life in Ohio and a speculative housing project proposal that she collaborated on. They also met with Nicole Hollant-Dennis, the architect of the African Burial Ground, and Elizabeth Kennedy, the landscape architect of Weeksville and a fellow Jamaican. And Elizabeth is really wonderful because she talks about the underpinnings of history and how critical a reading of history is in the making of black landscapes. It has to contend with the landscape we encountered in America, the landscape that we made in America, and the landscape that we constantly have to reify or adjust to and find ways to claim.

And her project at Weeksville is this really sort of clear affirmation of all of those things. She spoke with our students about the Dutch grid and the British grid, and how the site that is Weeksville emerged through this layering of American urban history. The students’ desk will be built the end of February.

KB: You wear so many hats—for BlackSpace, the Center for Architecture, and your own firm WorkUrban. How have you been able to refine this specific process and thread it through all of your work?

PR: For a long time, I’d been doing youth engagement, visiting high schools to talk about the architecture profession. When I was working for Gensler, Walter Hunt, who was a partner at that time, invited me to participate in the Learning by Design program at the CFA, working with Catherine Teegarden, who is still the Center’s director of education. When I was on the NYCOBA board, I had spearheaded a youth conference that was hosted at Pratt for our first two years. So by 2019 when I was invited by Cornell’s then-chair of the department of Architecture, Andrea Simitch, to lead a studio there was already a youth engagement practice agenda in play. I collaborated with fellow BlackSpace cofounders Ifeoma Ebo and Quardean Lewis Allen and his Brownsville, Brooklyn based organization Youth Design Center on that studio.

George Patterson, Senior Director of NYC My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, had been inviting me to talk about architecture and Black Space with his students. He had also met Quardean through me and knew what we were doing at BlackSpace.

George recognized that ‘Oh, architects make buildings, but Peter is talking about architecture in all these other ways.’ Or ‘Wow, okay. Architecture is not this closed envelope that we thought it was.’

In 20220 when I was again invited to lead a studio at Cornell the collaboration with George Patterson and MBK was natural. We created a studio in the middle of COVID that centered on living through the perspective of young Black boys. We had 14 Cornell students enrolled in the studio and they were joined by 14 MBK students enrolled at Medgar Evers Preparatory School in Brooklyn. The principal, Dr. Michael Wiltshire is a fellow Jamaican who built this very amazing school around Jamaican or very familiar Caribbean educational aspirations and agendas.

KB: The profession appears to be catching up to this thinking that architecture can support community due to the cultural climate in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder.

PR: The world and the nation are looking critically at what a racialized space is or what blackness means, in part, because of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Brownsville Heritage House and “Black Memory Work”

KB: So what of Brownsville Heritage House?

PR: BlackSpace had been invited to work in Brownsville by one of our grantors. And just by making ourselves present and available in the neighborhood, one of the spaces that we were introduced to was the Brownsville Heritage House, which is this 100-year-old collection of Black life in Brooklyn. It was founded by Mother Rosetta Gaston as a space for children within the Stone Avenue Library. The Stone Avenue Library is one of 26 libraries gifted to the city by Andrew Carnegie and had the first children’s reading room in America.

KB: It sounds like this is where the process of recognizing a racialized space dovetails with preservation.

PR: Yes. The building is the first children’s library in America, and the Brownsville Heritage House is in that building’s children’s reading room. So, in an interesting and amazing way, you have this historic Black community space in a historically significant American architectural space.

KB: Share some of the information important to preserving that space, which could only have come from its recognition as black space.

PR: When BlackSpace held its year-end celebration there in 2019, we asked Miriam Robertson, the third executive director for the Heritage House to say a few words. She talked for two hours. We were all mesmerized. It was like the experience of having healing hands laid on you.

That experience was significant for me, because it is a matriarchal-led institution. Each woman director is groomed by her predecessor to take over the organization, which is a long way for me to make to this point: Architecture for me is about language. And so, here comes Ms. Miriam using language to transform that event into the Black space that is approaching this 40-year anniversary of being a Black space, holding all of this Black history that has been locally determined to be significant. Later, the Cornell studio students also met Ms. Miriam, and again, her language was transformative, even on Zoom. She’s doing everything that I believe architecture can do: providing a way to feel and be transformed. It’s not just about materiality or spatiality. Language is a part of it. And my work begins at that moment.

KB: What do you say to architects working with tough timelines, impatient clients and feeling daunted by the idea of embracing such a lengthy process?

PR: It’s a practice area that just takes time to do. We used to call it programming, now we call it design strategy, and I wanted to create a space to really hone this practice area in my work with young people, I talked with the principal at Medgar Evers high school, and proposed a six-week summer paid internship. That was important too, that it would be a paid internship for the students.

KB: It’s a validation that the work is real.

PR: For the high school students, yes. That came from my own high school experience when I had a paid internship at an architecture firm, and my high school paid my salary through an initiative called the Training Opportunities Program (TOP). We had six students that started with us, and I was able to convince my former Gensler colleague Darius James to meet with our students on a regular basis, and with BlackSpace and with Ms. Miriam and Brownsville Heritage House stakeholders to support an understanding of what design strategy could be as a practice, and for me more importantly what it meant as a youth engagement practice. This was a great way to begin to test this practice muscle and build a practice around working with young people. It’s being implemented now.

KB: You call this process Black memory work. Is that a term that you’ve coined?

PR: It’s a term that just materialized itself as I was doing all this research. I didn’t coin it. I’m pretty sure I didn’t coin it.

KB: It’s critical to amplify it though, right?

PR: Yeah. That’s literally the work that I’m doing. And I think our whole conversation today has been about this. Language for me was the overarching thing in architecture. And so, that’s why I think, in practice, I was so drawn to design strategy, because design strategy is language. It’s how you communicate, describe, and plan. It blurs the distinction between drawing and representation because communication is being centered.

How do you construct a design practice that does not center visual representations? You lean on anchors that make architecture more about being relational. It is also means being very specific about how you interrogate history.

KB: I imagine some readers will think, ‘Isn’t that simply preservation work?’ What’s the difference?

PR: Preservation is the dutiful care of restoring and commemorating an original design, use, and intent for architectural spaces designated as being significant. But I often work in spaces a community holds to be significant, not because of the buildings’ intrinsic historical value, but because of the value the community has assigned them. The difference comes in recognizing that history, in that case, is a conversation about centering [certain values], and recognizing who gets to do the centering.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.