September 22, 2021

Two New Residencies Offer Indigenous Voices a Platform for Design Innovation

Different forms of knowledge through dreams, visions, and hallucinations change how we experience space.

Chris Cornelius, studio:indigenous

Given Indigenous cultures’ bond with storytelling and mythology, seeing beyond pragmatism can be fundamental in community-conscious design. “What about the subjective thinking in architecture?” Cornelius asks. “Different forms of knowledge through dreams, visions, and hallucinations change how we experience space.” In “building contemporary artifacts of culture,” he considers all sorts of knowledge as critical.

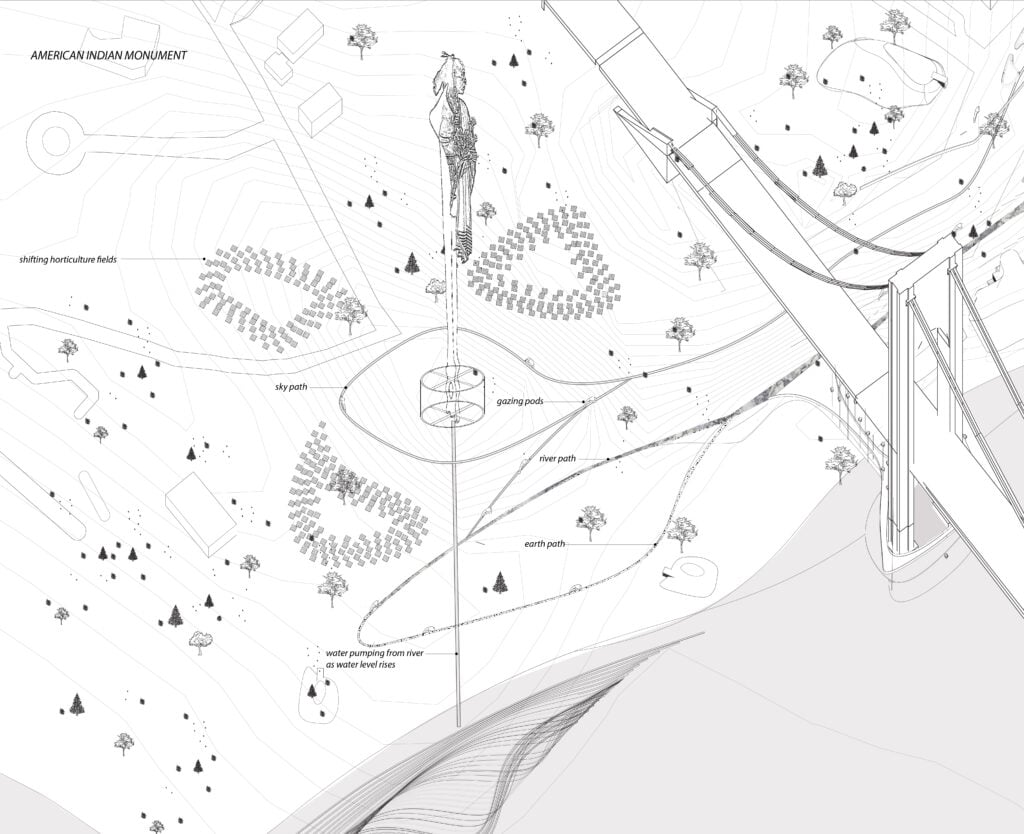

“Indigenous architectures’ relation to land and ecological services in a spiritual and physical way is inclusive of climate change challenges,” says Gallegos. “The pandemic and climate change make clear the need to consider architecture as part of a shared system and continuum of time.”

Cornelius spent a month in Hudson Valley along with other creatives in filmmaking, ecology, and linguistics. The Oneida Nation Wisconsin-based architect considers his participation in the Canadian Pavilion’s UNCEDED: Voices of the Land in 2018’s Venice Architecture Biennale a critical moment towards visibility. The fellowship and upstate New York’s spectacular sunsets gave him time to contemplate without the pressure of a deliverable. “I am at a point where focusing on thinking is a luxury between all logistical work,” he says.

Dwelling at the residency’s Ai Weiwei building—the only house the artist and activist made in the United States—was an unexpected joy. The main center and a guest house sit on the ancestral land of Muh-he-con-ne-ok, also known as the Stockbridge-Munsee Community. “The land is living and breathing with a history that is older than Forge—and there is significance in that,” says director of education, Heather Bruegl, who is Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee.

According to the executive director Candice Hopkins (Carcross/Tagish First Nation), the program, which awards each resident $25,000, “gives the platform to work within an artist-designed space that is clearly sensitive to its footprint on the land, its relationship to light, and the natural ecosystem of which it is a part.”

Cornelius sees the buildings as two animals that respect each other and one’s space. A similar land-centric approach to architecture is inherent in his own practice. “Indigenous value of relationality and relation to the mother earth,” are the tools he thinks are most needed in sustainable design. “Capitalism made us estranged from our mother and abuse her, and now it’s time to reconcile with its irreversible realities of climate change,” he says. For example, the architect thinks solutions to prevent or diminish the effects of flooding can be found in traditional Indigenous practices of forestry.

Generalization under the broad and often-times lacking umbrella of “Indigenous architecture” is common, but, he says, “When I design for other tribes, I search to translate that culture through a mutual spatial experientially.” The division he finds crucial is between Indigenous architecture and architecture for Indigenous people: “We need design conceived by the Native people through their unique way of understating the universe and expressed in that language.”

Gallegos (Santa Ana Pueblo/Jicarilla Apache) believes education and participation will lead towards a nuanced distinction in Indigenous architecture. “The current categorization aligns with political boundaries, and yet it is pertinent to be aware and recognize each group has their own histories, identities, and architectures that relate and do not relate to the current singular umbrella,” she says. “As more knowledge is shared and observed within architecture, the further distinction will assist in academia pushing beyond historic or regional reference and perhaps into subjects of sustainability, sacral space, and case studies to learn from and carry forward into practice.”

As part of the Lab’s strategy to make its email archive, digital correspondences, and social media platforms accessible to the residents, Gallegos wrote the Center for Architecture’s newsletter, conducted K-12 Architecture at Home Workshop, and created the Self-Guided Tour of New York with Urban Archive. Gallegos and her partners Summer Sutton and Charelle Brown, who also took part in the residency, interpreted ISAPD’s previous projects to highlight a group of Indigenous leaders through academic writing with personal interviews, podcasts, and virtual speaking events.

Lab Advisory Committee at the Center for Architecture selected the collective’s submission, titled Indigenous Futurism, for their inaugural fellowship program. Their proposal, according to executive director Benjamin Prosky, proved “their voices and material had been underrepresented at the Center and in the profession at large.”

The pandemic and the climate crisis have drastically prompted Gallegos to think about design that services the heavily-impacted Indigenous communities. “Both crises have impacted me to design at an urban scale and to model productive change which ultimately influences lifestyle,” she explains. 628,000 tribal households in Indian Country lack broadband, a rate more than four times of the general population. The architect highlights the impacts of inaccessibility on the youth’s education and specifically to consider a potential career in architecture. “These challenges strengthen my work to boost architecture as a solution-based, creative profession for Indigenous peoples to join academically and to continue legacies of architecture which have thrived for time immemorial.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

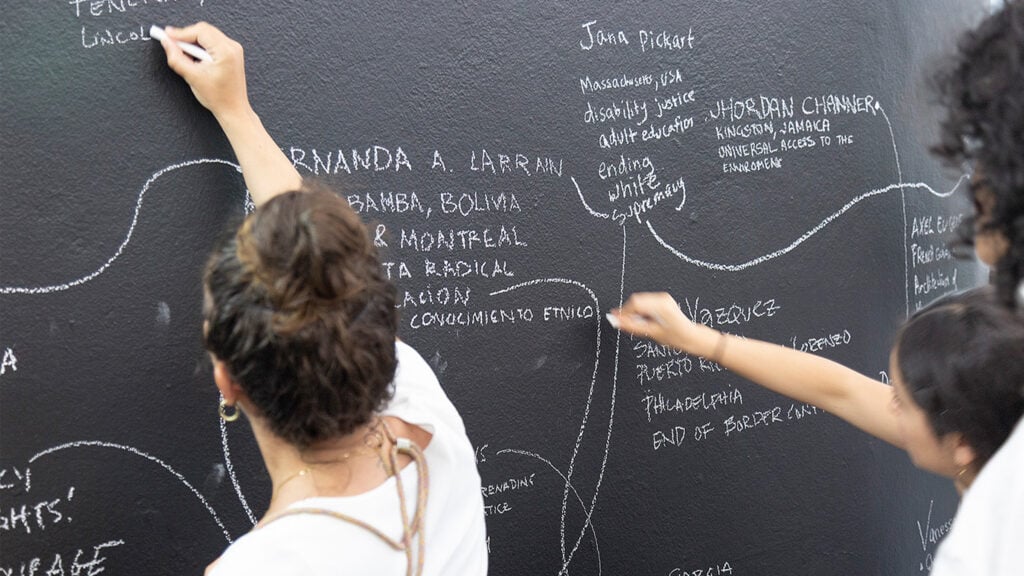

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.