October 14, 2019

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, Revisiting the Meaning of “Native Architecture”

Chris Cornelius of studio:indigenous speaks with Metropolis about (de)colonization in the practice, education, and experience of architecture.

“You can count on one hand the number of indigenous professors of architecture who are tenured,” remarks Chris Cornelius, who teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and is the founder of studio:indigenous. It’s dark jab at architecture’s professional and academic establishment, and one that reflects the woeful underrepresentation of native practitioners in the architecture and design community.

Lack of adequate representation is not an issue of supply, but rather one of recognition and affirmation of work already being done. (As the old call-and-response goes: “Where are the women architects?” “We’re right over here!”) Over half-a-millennium after Europeans’ arrival on Turtle Island, the livelihoods, traditions, and contributions of indigenous communities continue to be trampled upon, taken for granted, or otherwise stereotyped and ridiculed. Colonization is ongoing, evident in structural disinvestment in native communities; disparate socioeconomic and health outcomes; broken land treaties that have yet to be addressed; and even rampant appropriation in the cultural and academic sphere. But importantly, if colonization is ongoing, then so must the process of decolonization.

Cornelius is a citizen of the Oneida Nation and grew up on a reservation near Green Bay, Wisconsin. The research he conducted as part of his master’s degree at University of Virginia focused on “translating native culture into architecture,” jump-starting a career that has spanned pedagogy and practice. Cornelius has designed several installations (he unpretentiously calls these “public art kind of things”), such as the award-winning Wiikiaami, which was displayed as part of Exhibit Columbus 2016-17, as well as the Indian Community School of Milwaukee, his largest project to date. He frequently collaborates with indigenous professors and practitioners north of the United States–Canada border, such as a current project on housing for a First Nations community in northern Manitoba.

Here, Cornelius discusses the utility of land acknowledgements, what native architecture can look like, and the recent infatuation with so-called “indigenous building practices.”

AB: In grad school you focused on translating native concerns into the built form. Could you talk about what that means? Is that an aesthetic consideration, a material one?

CC: I was interested in digging into just that. There are buildings being made these days for native people that take the form of a normal building you’d see anywhere else, but with native iconography. And there are buildings that kind of look like animals, like a turtle. There’s an elementary school on my reservation, which was built in the ‘90s, that looks like a turtle. And I thought there has to be a better way to translate native culture into a building and an architectural experience. Because once you get beyond that surface level, what does it really mean to build for a certain culture? So it started to become a kind of methodology for working because I purposely tried to resist either of those expected things, and figure out how to turn native features into experiences. If culture is embedded in architecture in a way that you experience it, it’s going to have much deeper resonance.

AB: Would you resist any attempt to say that there is a certain essence or a nature to indigenous building? Should there be an expected, coherent body of aesthetics that kind of maps onto nativeness?

CC: When we say indigenous architecture, for me, I don’t think of it as a style. It’s more of a way of thinking and a kind of movement. So there are other indigenous designers that would translate that differently. At last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, I was part of the all-indigenous team representing Canada. We had long discussions about this very subject—how to encapsulate our work into a body of ideas. The conclusion we came to was that we’re all of a like mind in using culture as the guide. People may look at our work and see patterns, colors, or even forms, and say, “Yes, that’s that native.” But I think it’s a little bit more embedded. I do try to make those considerations evident in the representation of the work, though. In the way that I draw, render, or model a design.

AB: I was going to ask you about your drawings because there’s something very expressive about them. What’s the role of drawings and representation in your process?

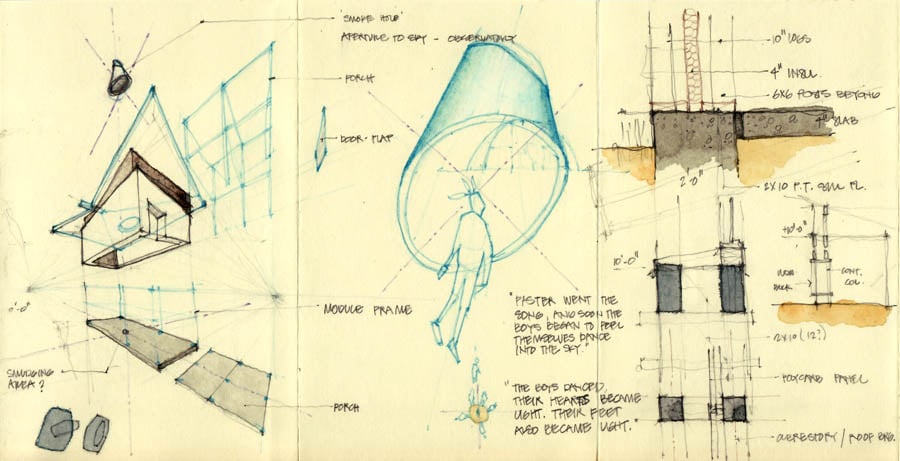

CC: I like to say that, for me, drawing is medicine, meaning that it’s a way to make myself feel better. Most of my drawings started out as self-initiated explorations. I’m trying to draw things that haven’t been drawn yet, rendering visible thoughts that might not be fully articulated. In architecture when we think about representation on a base level we conceive of the design and then we represent that. So we know what the designed object is and then we represent it. Whereas I’m more interested in how the representation can be generative. So they’re graphic ways of articulating thoughts that haven’t been able to find articulation or description. My Domicile series of drawings, for example, was a way to try to get out of making something architectural from some sort of metaphor, the thought pattern of, What if we didn’t know where they came from? Or if we didn’t know what timeframe they came from?

AB: There’s a growing popularity at cultural events or in academic texts of land acknowledgements, verbal or written or even built. Do you see this as a step in the right direction, or is it maybe ultimately a hollow gesture?

CC: I think that they’re very important, but I don’t want them to get lost in the mix. Something should happen because of them, right? It should frame the larger consciousness, which needs to get embedded more deeply in how we view U.S. history. We’re only starting to understand that our country was founded on the backs of slaves. But it goes even deeper than that, to understand that before Europeans came here this wasn’t just some sort of frontier of nothingness or of wildness. So we need to acknowledge that in the way that we talk about this country. And on the further end of the spectrum, maybe a next constructive step is honoring all of the treaties that were made with indigenous peoples and subsequently broken, along with some sort of reparation.

AB: Clients—especially municipalities, institutions—often commission you for a certain type of work. Are you comfortable being seen as indigenous architect, and not maybe, an architect who is indigenous and works in many indigenous contexts?

CC: I take on that title, that descriptor with pride. However, I do think that our discipline likes to pigeonhole people. For some reason that seems to make people comfortable. But in being pigeonholed in that way, it narrows what I’m trying to do. It’s always been of primary importance to me to produce good architecture, and my culture is just always going to be a part of me. So that’s inherent and tacit in my work and the way I think about it. But I’m not always just trying to produce “indigenous architecture.” I want to be a part of a larger design dialogue. If we’re having a dialogue through publications, exhibitions, awards, symposiums, biennials, whatever, I want to be a part of that conversation.

AB: Climate change and sustainability are obviously on the tips of everyone’s tongues these days in the building and construction world, and many seem eager to see so-called “indigenous building practices”—those sensitive to site, context, materials—as a solution. What do you think about that?

CC: People often ask me about my work, especially the Indian Community School in Milwaukee, “Isn’t it a bit like LEED? Is that something you looked at?” And it really wasn’t, because if you’re consistent and respectful to local culture, those things will just flow. It’s about responsibility, with respect to materials, the site, the clients, the people who use the final product. The answer to those questions of sustainability may not be as apparent as Western thinking might want it to be. It’s about how you begin to think of something—for me, I like to think about architecture as an animal: Animals exist in the context that they dwell in, and they survive fine. They don’t need to learn anything; it’s inherent. So I think about a work of architecture like an animal, asking, How would this thing inhabit the earth? How should it touch the sky? Is it a predator or is it prey? Does it fly? Does it swim?

Certainly there are answers to the climate crisis in indigenous thinking, but the answers are not formulaic. So for instance, think of the way that we teach building technology to architecture undergrads. Let’s say it wasn’t just about all of the performance and functions materials and assemblies. What if we posed broader questions like, When you put this assembly into the world, how big is the impact and what are you impacting? How do materials get to the site? How are they shipped and manufactured? That guides my teaching, my criticism, my pedagogy, all of that. That’s how I bring my culture into how I teach.

AB: What indigenous architects inspire you? And are there any hubs for this type of work? Where is an “indigenous architecture scene” playing out?

CC: Everything for me goes back to Douglas Cardinal. He’s the elder in our field. He found a way to create his own voice as an indigenous architect in Canada and then was received in the discipline along with anyone else. He did a lot of significant work, and that’s the model for me.

There are people working on the west coast of Canada—Alford Waugh, Patrick Stewart—who are doing fantastic work. There are a lot of people in Winnipeg around my age who are also doing great work, like Ryan Gorrie and David Thomas. We all became part of this network because of the Biennale. That work is actually on exhibit at the National Museum of History in Ottawa, and it is really us telling stories about how we think about architecture. I mention a lot of places in Canada because indigenous architecture seems to be much more organized in Canada. And then one of the cocurators of the Biennale, David Fortin, is the head of architecture at Laurentian University. I believe he’s the first indigenous head of an architecture department in the United States and Canada.

AB: Thanks so much for your time, Chris. Is there anything you want to mention to close things out?

CC: I think it’s important to note, when we discuss who colonized whom, of course it’s the Europeans who colonized indigenous peoples, but it’s not meant in an adversarial “us vs. them” way, which is not very productive. I think the way we educate students about architecture can change, and I would suggest we look at the academy in the United States more broadly and critically, at the possibility of decolonizing the curriculum. A place to start is to think about things a little differently. Maybe it’s not as systematic, but practitioners and students and everyone should be asking themselves: Am I furthering colonization in what I’m doing, or is there a way to emancipate myself from that?

Metropolis would like to acknowledge that it occupies and operates on the traditional land of the Lenape people, as well as across unceded indigenous territory across the continent and globe.

You may also enjoy “Deconstructing Degrowth at the Oslo Architecture Triennale.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025