October 18, 2019

From Bauhaus to Bunkers: The Aspirational Architecture of Hollywood Villainy

Why do bad guys in the movies always live in “good” houses? A new book digs into that question.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the rise (and rise and rise and rise) of supertall, superluxe, plutocrats-only developments in cities around the world would inspire anxiety and dread. Yes, they junk up the skyline. Yes, they’re harbingers of a particularly virulent gentrification. Yes, many of them are laundry machines for ill-gotten wealth. But set that all aside. For decades, we’ve been conditioned to expect bad things from showy homes—because that’s where cinema’s greatest villains live.

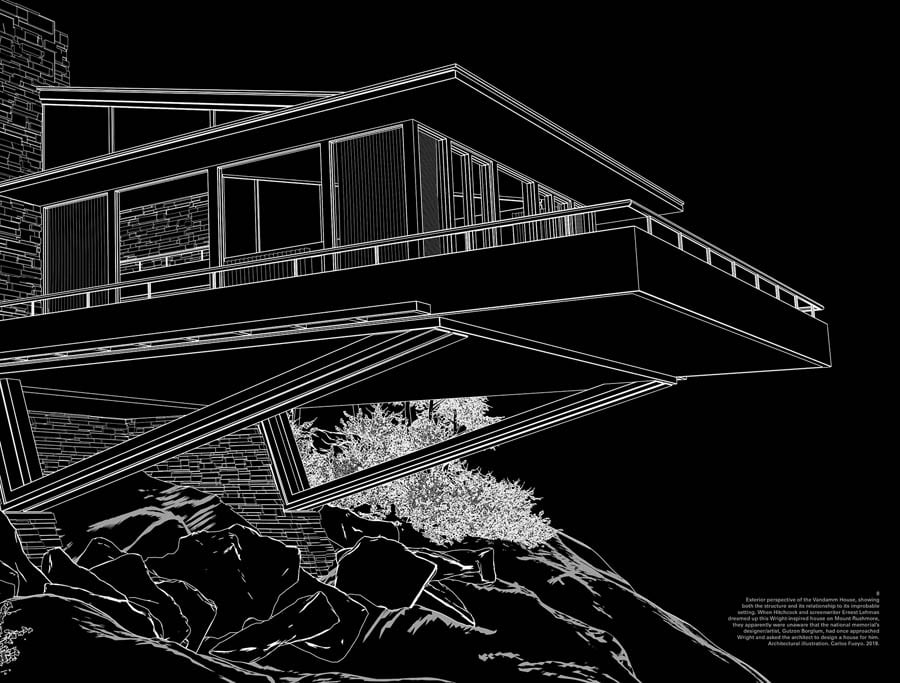

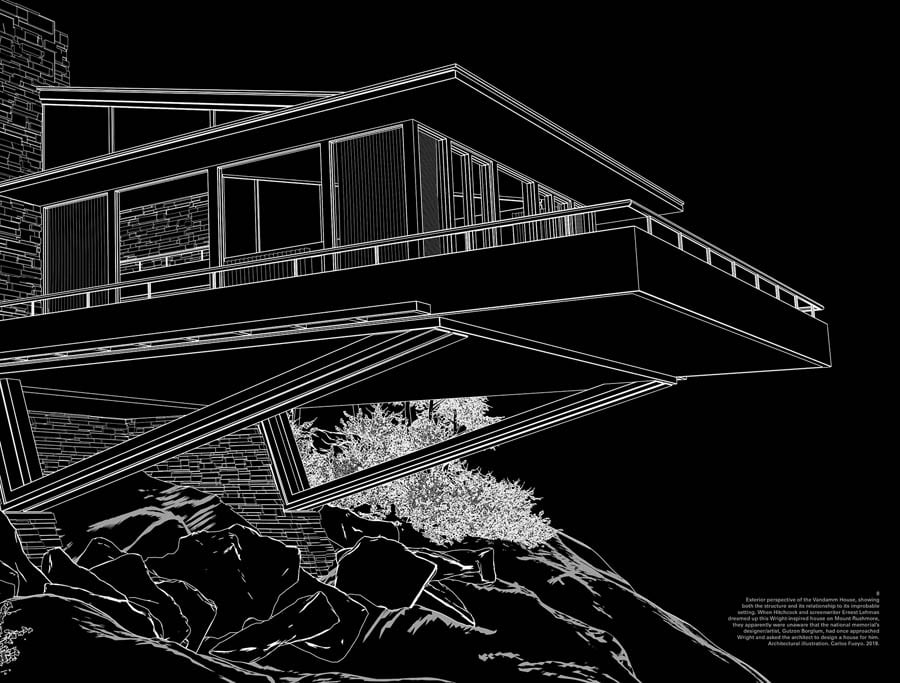

From the Frank Lloyd Wright–inspired Vandamm House in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959) to the glassy tech-bro pad of Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) and a couple dozen Bond villain bases in between, moviegoers have been tipped to just how dastardly a villain is based on where they hang their hat. The cleaner the lines (and the linens), the more ostentatious the digs (and the collections), the more bad the baddie.

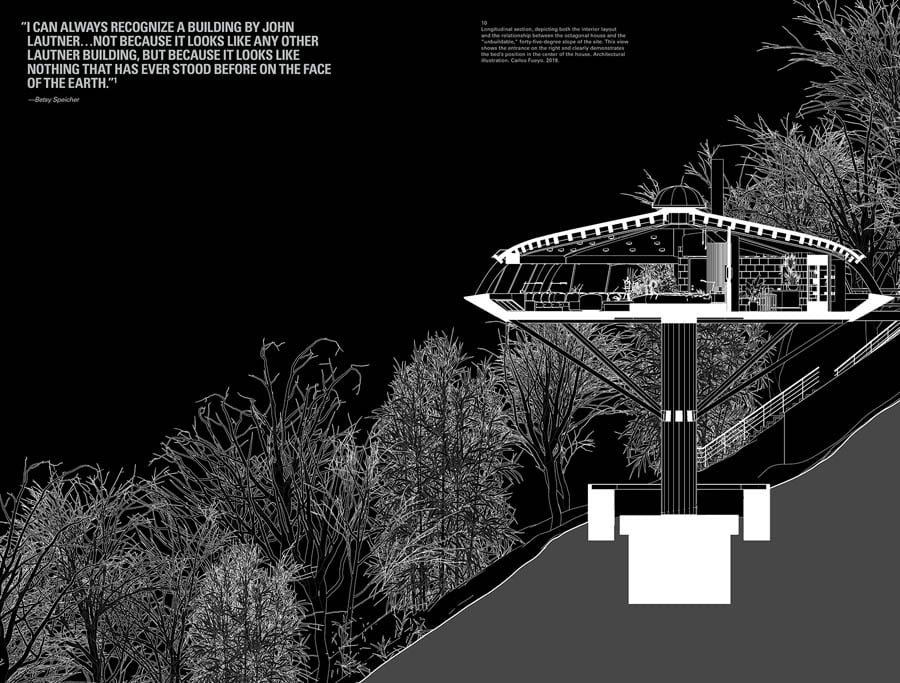

But why do bad guys live in good houses? Lair: Radical Homes and Hideouts of Movie Villains (Tra), a new book from architect Chad Oppenheim with Andrea Gollin, attempts to answer this question. Due to be published November 5, the elegant, oversize volume—tall, heavy, with silver ink printed on black pages—is a long overdue interrogation of the architecture of movie villainy. The book peeks behind the spaces of real-existing structures (such as John Lautner’s Malin Residence, used as a Peeping Tom perch in 1984’s Body Double) as well as fictional ones (like Syndrome’s meta-lair in 2004’s The Incredibles) using a mix of production stills and graceful renderings created by visual effects expert Carlos Fueyo. Interviews with directors (Michael Mann, Richard Donner) and production designers (Ken Adams, Richard Eggleston) add context to the illustrations.

The book features 15 films, which helped frame an October 10 Archtober event at the NeueHouse. Oppenheim—joined by Fueyo and critics Owen Gleibermann, Leah Goldblatt, Jason Bailey, and Chris Nashawaty—opened the discussion about the book explaining that a lair had to be “aspirational” to merit inclusion. “This is all about real estate. These are all aspirational, desirous places.” Goldblatt added, “It’s interesting that these movies are asking you, essentially, to want to be the bad guy.”

That was certainly Oppenheim’s experience. Lair took three years to complete but represents 40 years of grappling with these devious domains, which began with the 1974 James Bond film The Man with the Golden Gun. After watching Roger Moore’s Bond battle Christopher Lee’s dastardly Scaramanga on the latter’s private island (Ko Khao Phing Kan, off the southwest coast of Thailand), the young Oppenheim “either wanted to be an evil villain or an architect.”

Unsurprisingly, Bond bad guys are well represented in Lair. Besides Golden Gun, Oppenheim digs into Blofeld’s volcano bunker from You Only Live Twice (1967)—its underground city of crime, complete with a ballistic rocket, became the prototype for all sorts of lairs, including Dr. Evil’s in the Austin Powers series—as well as Blofeld’s villa in Diamonds Are Forever (1971) and Karl Stromberg’s arachnid submersible Atlantis in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). “They actually want to change the world,” Oppenheim said of movie villains. “[Stromberg] wanted to make a new world that emerges from the water. So they’re very utopian, in a way. They actually believe they’re doing the right things, like most megalomaniacs.”

That bad guys live in cool houses—or ridiculously tricked-out man caves—is crucial to creating narrative and emotional tension, be it in a Bond adventure or a drama like Ex Machina. How could someone with such good taste be so evil? Do we really want to see this sweet house blown up? What does it say about me that I would (maybe literally) die to live there?

Movie lairs weren’t always this way. The first bad-guy hideouts tended to be decrepit castles (Dracula) or grungy apartments (M), if there was a hideout at all. But the panelists agreed that things changed with North by Northwest, a sexy wrong-man spy caper, where James Mason’s Phillip Vandamm lived in an achingly Modernist home behind Mt. Rushmore. “Hitchcock creates the whole idea of the villain’s lair,” Gleiberman said. “He creates it out of thin air, out of something that doesn’t even exist.” (The house was a set and exteriors were extended with the help of matte paintings.)

From North by Northwest came the templates for James Bond and the refined villain who cared more about interior design than the value of human life. (“I feel like a lot of these villains either want to be old-world gentlemen or super-hyper modern,” Greenblatt said.) But for every Vandamm is a film fiend who’d rather go bunker than Bauhaus, from Blofeld’s volcano to Lex Luthor’s bungalow beneath Grand Central Terminal in Superman (1978).

There’s an analysis to be had for why that is. Gleiberman chalked it up to a Freudian search for the womb. Oppenheim said the literal definition of “lair” is a place an animal seeks shelter. Others mentioned the connection to Hitler—villain of villains—and his end-of-days bunker.

But maybe it’s simply just a reflection of real-world authoritarian design.

“The first point of reference [in designing these sets] typically is Brutalism,” Fueyo said. “When it comes to villains, it might be because it’s the Cold War, the Soviets, and the idea of an architecture for the people [that’s really an] expression of totalitarianism without seeming totalitarian. We forget that that’s Modernism, as well. It’s not just Brutalism, it’s the other half of Modernism. It’s the half that went to the wrong country.”

“It’s an architecture of propaganda,” Oppenheim added. “It’s all about convincing people that there’s power and thought and might in the architecture that supports the message. And the key ingredient seems to be concrete. It’s all about this incredibly strong material that fortifies the evilness.” Movie despots—they’re just like (the real-life tyrants who oppress) us!

You may also enjoy “Finding Women Architects in Where’d You Go, Bernadette?”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]