November 28, 2023

Lana Del Rey’s Music Has Always Taken Architecture Very Seriously

“Her repertoire is at once an exercise in memory and a book representing the lives she yearns for.”

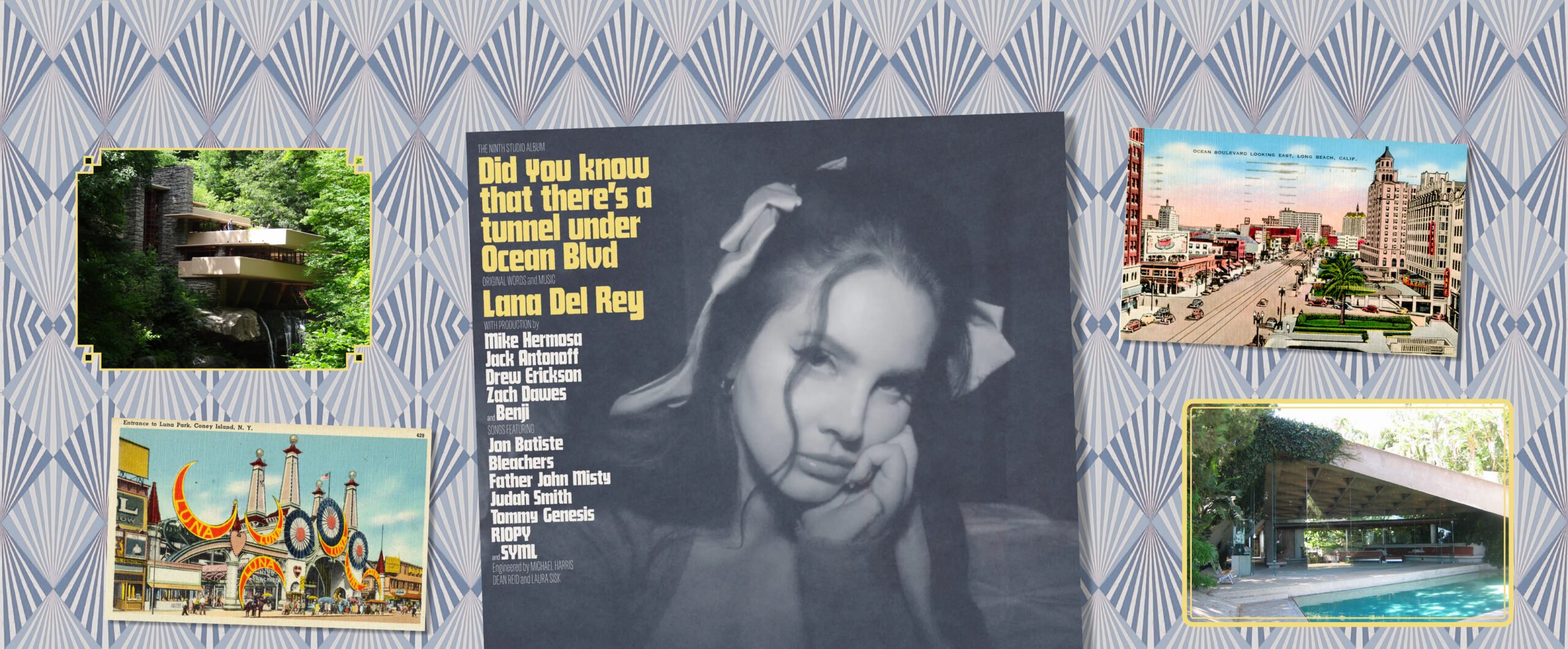

Lana Del Rey’s music, popular among both millennials and Gen Z, is known for her assorted references to a lost time. Her songs, bursting with yearning, regret, and romance, often feature prominent musicians and cultural figures, from the 1950s–1970s. She compares her ex-boyfriend to James Dean or Coachella to Woodstock. John Denver, Eagles, and or Harry Nilsson make graceful appearances in her lyrics. Her repertoire is at once an exercise in memory and a book representing the lives she yearns for.

Brooklyn Baby: The Places and Spaces in Lana Del Rey’s Music

In her songs, Lana Del Rey uses neighborhoods, cities, and buildings to allude to the cultural significance of architecture and urban codes. In 2011, early in her career, she said, “NY architecture alone is enough to inspire a whole album. [M]y early stuff was mostly just interpretations of landscapes.” Coney Island in “Carmen” (2012), Rikers Island in “Off to the Races” (2012), and the Hamptons in “National Anthem” (2012) are hard-to-miss references for New Yorkers and lovers of the city. Lately, Los Angeles, the singer’s home base since her music career took off in the early 2010s, has been a vibrant setting for her stories. Griffith Park, Skid Row, Venice Beach, Bel Air, Rosemead, Mariners Apartment Complex—they all make appearances in her songs to build layered meanings in stories of love, fame, or loneliness. Some neighborhoods are more special to her than others. For example, Hollywood is simultaneously a place-time of glamor and decay for the singer. In her unreleased song “Hollywood” (2012), the neighborhood is an aspirational place where she realizes textbook dreams like driving expensive cars, or “walking on the water and dancing like (Janis) Joplin.” In another unreleased song “Hollywood’s Dead” (2012), the neighborhood is a past time where “Elvis (Presley) is cryin’ / (Sid) Vicious in flames / (Ruth) Roland is dying.”

However, she can be on the nose with her architectural references, too. In “Art Deco” (2015), she likens the subject of the song, a woman who is trying too hard to impress others, to the architectural style of the 1920s saying: “You are so Art Deco out on the floor / Shining like gunmetal, cold and unsure.” After hearing these lyrics, all I can think of is that I have never heard a more succinct explanation of the Art Deco style before: She captures the insecure showiness of the post-Depression era perfectly.

It’s clear that Lana Del Rey doesn’t throw architectural references around just to look cool. She knows them deeply, and uses them as needed. She once shared a video of Frank Llyod Wright speaking about architecture in a Facebook post and wrote, “My life’s passion is building and painting—and for that reason my biggest inspirations are Frank Lloyd Wright and John Lautner. I think of their architecture as frozen music and anytime I’m in one of their spaces I’m reminded of how malleable my feelings are and how affected they can be by my environment.”

She referred to the famous architect once again when she was criticized for singling out women singers of color for their songs’ sexual content. She defended herself with a Frank Llyod Wright quote which read: “If you invest in beauty, it will remain with you all the days of your life.” Lana Del Rey’s love for architecture has not escaped her fans, either. I found “a reading list for Lana fans” on a fan forum, and in it, In The Nature Of Materials: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright 1887-1941 by Henry-Russell Hitchcock is listed among classics such as Lolita by Nobokov, Howl by Allen Ginsberg, and the Bible.

Off to the Races: Lana Del Rey’s Visual References

Today, no pop star can be understood without the visual component of their artistry. No matter how beloved Lana Del Rey’s songwriting is, her videos still make a considerable chunk of her artistic output. And since the beginning of her career, Lana Del Rey has used architecture to make her point in the visual realm as well. In the “Born to Die” video (2011), the Palace of Fontainebleau with its ornate interiors is the heaven where the protagonist goes to after dying. In “High by the Beach” (2015), the singer’s Malibu home nearly fails to protect her privacy from paparazzi who come dangerously close to the beachfront house in a helicopter only to be shot down by a large firearm triggered by the singer herself. In “Lust for Life” (2017), Lana Del Rey and the Weeknd sing on top of the Hollywood sign. Then, in a knowing subversion of Peg Entwistle’s tragic suicide—the British actress famously jumped to her death from the exact same spot in 1932, becoming a symbol of the cruelty of show business—Lana Del Rey slides off the sign into a flowery meadow as she sings “with a lust for life.” And as a complete embrace of urban texture in her visuals, the singer walks across L.A. as a giant in the video of “Doin’ Time” (2018), reminding us of the cult film Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. Time and again, in many other songs and videos, Lana Del Rey skillfully wields images of architecture and urbanism to underpin her music with deep cultural references.

Lana Del Rey is neither the first nor the last singer to draw from architecture and urban folklore in her music, but these examples show that she is special among her peers for taking the built environment seriously. As a life-long student of architecture who likes to know the histories of urban spaces I live in, and a pop culture enthusiast who likes learning things from it, I wish more artists considered architecture as an important component of what they sing about, because pop music is often so ephemeral. The songs that remain relevant across time are those that touch on the real and complicated issues of life. When Lana Del Rey uses architecture and urban folklore in her songs to complete her storytelling on how time and destruction test our contemporary lives, and how we feel in the midst of all these larger forces acting on us during the turning points of our lives, she is clearly inspired by her conception of architecture as music frozen in time. I believe her music benefits from the temporal qualities of architecture, and that gives it endurance amidst pop culture’s rapid consumption and deterioration.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Archtober Invites You to Trace the Future of Architecture

Archtober 2024: Tracing the Future, taking place October 1–30 in New York City, aims to create a roadmap for how our living spaces will evolve.

Projects

Kengo Kuma Designs a Sculptural Addition to Lisbon’s Centro de Arte Moderna

The swooping tile- and timber-clad portico draws visitors into the newly renovated art museum.

Products

These Biobased Products Point to a Regenerative Future

Discover seven products that represent a new wave of bio-derived offerings for interior design and architecture.