August 5, 2015

Meet Irving Harper, the Man Behind the Marshmallow Sofa

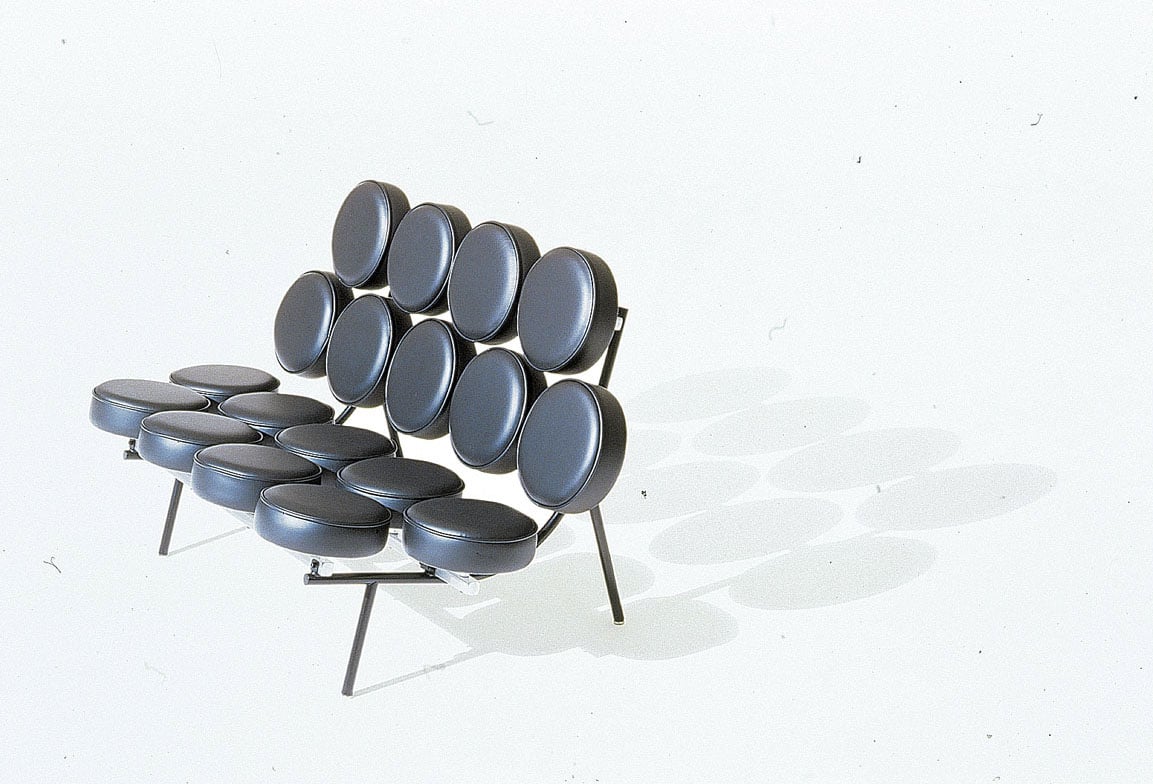

You don’t know his name, but you definitely know his work: Irving Harper, the man behind George Nelson’s Marshmallow Sofa.

Harper’s designs for Herman Miller include the Marshmallow Sofa (1956) and the company’s logo (ca. 1940s).

Courtesy Herman Miller

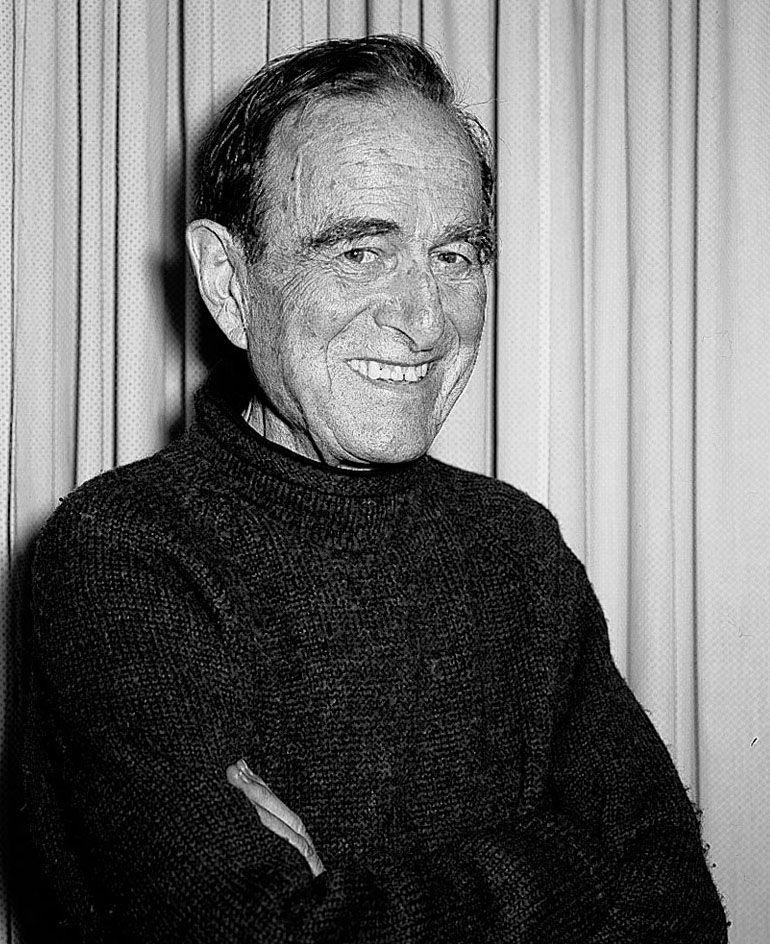

Irving Harper, designer of the Marshmallow Sofa and several other classic midcentury modern designs, has died at the age of 99. In June 2001, editorial and brand director Paul Makovsky penned the authoritative profile on Harper, whose work had, for decades, been erroneously attributed to his mentor George Nelson. We republish the story—what remains one of the magazine’s proudest articles—below.

On the day I visit Irving Harper at his house in Rye—a comfortable suburb just north of New York City—he’s preoccupied with finding orange tile. It’s been 25 years since he first had the brightly colored tile installed in his kitchen floor, and he is finding it difficult to get the right shade. “It should be so easy,” he says, “because orange is really of the moment right now.” Harper seems reluctant to change it.

His house, a rambling late-nineteenth-century farmhouse that he shares with his wife, Belle, a labor lawyer, is the kind of domestic trophy any young designer would kill for. It’s filled with vintage Modern furniture, prototypes, antique pieces, well-thumbed books, vernacular objects from around the world, and the intricate paper sculptures that Harper has been making for the past 40 years. There are more than 500 of them in the house and barn: models of imaginary buildings, Picasso-esque figures, fantastic animals. Occasionally, a piece is done in a different medium—toothpicks, straw, twigs, spaghetti.

Chances are you haven’t heard of Irving Harper, but you have seen his work. The Marshmallow Sofa is the quintessential icon of American Modern design. Designed by George Nelson, right? Well, not exactly. And those vintage Howard Miller 1950s Ball Clocks that you keep seeing on Ebay? Harper created them. He is one of the many designers who worked in the Nelson office during its glory days.

“I still see a lot of people who worked there,” Harper says. “Suzanne Sekey, Ernest Farmer, Tobias O’Mara, George Tscherney, Lance Wyman, John Pile. I saw a lot of Gordon Chadwick and Bill Renwick before they died.” He goes on to mention other illustrious Nelson alumni: George Mulhauser, designer of the Coconut Chair (recently reissued by Herman Miller); Robert Brownjohn, creator of the titles for Goldfinger; Ettore Sottsass, who spent six months there on a U.S. student visa; even Michael Graves, it turns out, did a stint in the early 1960s.

During the heyday of American Modern industrial design, designers like Rohde, Dreyfuss, Bel Geddes, and Loewy were treated like celebrities—one-name pop stars. “They were considered geniuses,” Harper says, flipping through a portfolio of furniture and products, his life’s work. “Individuals responsible for transforming the look of American product. So there always had to be one name associated with the work. We couldn’t just spread it around.” He pauses for a moment. “Well, that’s fine. I’m grateful to George for what he did for me. While he was alive I made no demands whatsoever. But now that he’s gone, whenever the Marshmallow Sofa is referred to as a ‘George Nelson design,’ it sort of gets to me. I don’t go out of my way to set things right, but if anybody asks me who designed it, I’m perfectly happy to tell them.”

Irving Harper in 1954

Courtesy Irving Harper

Pile, who worked in the office during the 1950s when it was officially known as George Nelson and Co., offers an explanation on the murky issue of authorship: “George’s attitude was that it was okay for individual designers to be given credit in trade publications, but for the consumer world, the credit should always be to the firm, not the individual. He didn’t always follow through on that policy though.”

Harper leads me upstairs to the studio where he spends much of his spare time making paper sculptures. He opens a cabinet, and out roll dusty blueprints from the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The Plexiglas exhibit, the Anthracite exhibit, and the Home Furnishings Focal exhibit, all projects he worked on as a draftsman in Gilbert Rohde’s office. After the war he managed to get a job at Raymond Loewy Associates designing interiors in the department-store division. He calls it “a conveyor-belt operation.” When Nelson offered him a job in 1947, he jumped at the chance.

Nelson had landed the Herman Miller furniture account the year before, while he was still a writer at Fortune magazine. An article Nelson wrote blasting the American furniture industry had impressed D. J. DePree, president of Herman Miller. So Nelson and Farmer, a German refugee Harper knew from the Rohde office, designed the preliminary line. “They needed an ad, so Ernest suggested I take a crack at it. I had no graphic-design experience whatsoever, and you could tell from that first ad.”

The orange tile in Harper’s Rye, New York, kitchen.

Courtesy Criswell Lappin

He pulls out the ad from one of his art portfolios. Because there was no furniture in the line yet, Harper had no photos to work with—nothing to base the ad on except a name. He decided to do it graphically and invented a big M, for Miller. It’s pretty much the way it looks today, except that the proportion was a bit narrower and higher, and it was done in wood grain because, Harper explains, the company was heavily into wood furniture at the time. “I continued to use the M and refined it as the ads went on. The Herman Miller logo was something they got for free, and they loved it.” He chuckles. “There was no project to do a logo. It was probably the cheapest logo campaign in advertising history.”

Harper moves to the other side of the studio and pulls out a file of clock designs. When Nelson got the Howard Miller Clock company account (Howard was the brother of Herman), he gave Harper the responsibility of handling it. Harper’s initial idea was to create a piece of sculpture. “To omit numbers and have an abstract object that moved on the wall was something no one was doing at the time,” he says. Once or twice a year he would design a group of about eight clocks, which would then be presented to Howard Miller and put into production.

During his 17 years with Nelson, Harper designed graphics, furniture, interiors, and exhibitions, in addition to a whole spectrum of domestic goods—from china sets, plastic dinnerware, and lamps to typewriters, slide projectors, fireplace accessories, and record players. “The atmosphere was like a school,” he says. “An atelier-studio with everybody running around. Nelson would let you take all the time you wanted.”

The idea behind the Marshmallow Sofa was born in 1954. According to Pile, a salesman from a Long Island plastics company visited the office and told them about a new technique for making self-skinned upholstered cushions. It involved putting a coating into a mold and then injecting plastic into it. The technique’s limitation—cushions could only be 10 to 12 inches in diameter—became the animating feature of the design.

The paper sculptures Harper has made for the past 40 years often use shapes—sometimes even actual parts—from the clocks he designed for the Howard Miller Clock Co. in the 1950s.

Courtesy Irving Harper

“I have to tell you,” Harper says, looking at a photo of the iconic object, “I designed it in one weekend. I made a little model and brought it into the office. It was supposed to be a joke, sort of a game, because I’d never done anything that looked like that.” The design was sent for prototyping.

“The only problem was the plastics company couldn’t actually do what they’d promised,” Pile recalls. “But the design was sufficiently interesting that they made it anyway, making the cushions with plywood and conventional upholstery.” It was given a catalog number and made a product.

After all these years Harper still seems frustrated by the process. “So instead of making a sofa, you had to fabricate 18 of these damn cushions just for the one piece. That was the kiss of death. It destroyed the concept. But there was no other way to build it in those days. It turned out to be more expensive because they had to do these cushions by hand, which was ridiculous—and explains why Herman Miller made just 200 of them.”

Harper in 2001

Courtesy James Westman

I ask Harper what he thinks of Nelson. “I have a tremendous respect for him. He made it all possible. His biggest contribution was to allow designers to do their own thing. He never pressured you to design anything you didn’t want to do. He was like Diaghilev, able to locate talents who were brilliant in their own way, allowing them to flourish. Though we were never paid a lot, he was never a bottom-line man. He pitched it all away on designs.”

After Harper left the Nelson office, he hooked up with Phillip George and started his own firm, Harper+George. They did work for Braniff Airlines, Jack Lenor Larsen, and Hallmark Cards, among many others. “I wanted to see what it felt like to be a boss,” the 84-year-old Harper says. “Everybody has that feeling sooner or later, whether they act on it or not.”

He left the office in 1983, but continued to create his paper sculptures. Recently he’s been brought out of retirement. When Michael Maharam came across a roll of vintage Nelson fabric prints, he put in a call to Nelson’s 82-year-old widow, Jacqueline. She directed him to Harper, who confirmed that he had been responsible for designing the textile prints for the Nelson office.

Working closely with Harper, Maharam is bringing back textiles first created in 1950. According to Maharam, at one point he showed Harper the intended fabric. “He went through a honing process of coming up with a narrow selection,” he says. “Then he flipped the fabric over and said, ‘This is really more like what I had in mind.’” Maharam happily obliged. “The finished result is really crisp and a very fair interpretation of the original print. But now as a weave, it’s suitable for seating. It’s durable and will do what it needs to do to be a practical product.”

At the end of the day, we go downstairs and Harper shows me his latest creation. He’s taken an old hat form and, using spokes from a Howard Miller clock he had lying around in a box, made a sculpture that’s one part Brancusi, one part African headdress. We talk about this midcentury mania—how it’s suddenly all come back into fashion. He knows all about the Marshmallow Sofa that sold at auction last year for more than $40,000. “I’m delighted,” he says with a modest chuckle, unfazed by it all. “I wish I could say more than that. I’m pleased.”

Harper has the kind of home any young designer would kill for, filled with prototypes, antique pieces, vintage Modern furniture.

James Westman

Harper’s house is virtually a Modern gallery of bold textiles and classic furniture—some of which are his own designs.

James Westman

There are more than 500 of them in the house and barn: models of imaginary buildings, Picasso-esque figures, fantastic animals. Occasionally, a piece is done in a different medium—toothpicks, straw, twigs, spaghetti.

Courtesy James Westman