September 10, 2019

Urban Renewal, A Blight on Other American Cities, Sparked an Architectural Renaissance in Pittsburgh

The editors of the new volume Imagining the Modern argue that the reviled federal program was responsible for creating the postcard Pittsburgh.

It’s been decades since the phrase “urban renewal” enjoyed anything but obloquy. Except in a few rare cases, salvaging even an ember of positivity from the term is nigh impossible. In Pittsburgh, a pioneer at tearing itself down, urban renewal went by another, more grandiloquent descriptor, that of “Renaissance.” Of all the American cities that undertook this regime of self-directed injury, the “new” Pittsburgh has aged considerably less badly in the popular, and particularly, the local imagination. The reasons why are explored in Chris Grimley, Michael Kubo, and Rami el Samahy’s Imagining the Modern: Architecture and Urbanism of the Pittsburgh Renaissance (The Monacelli Press).

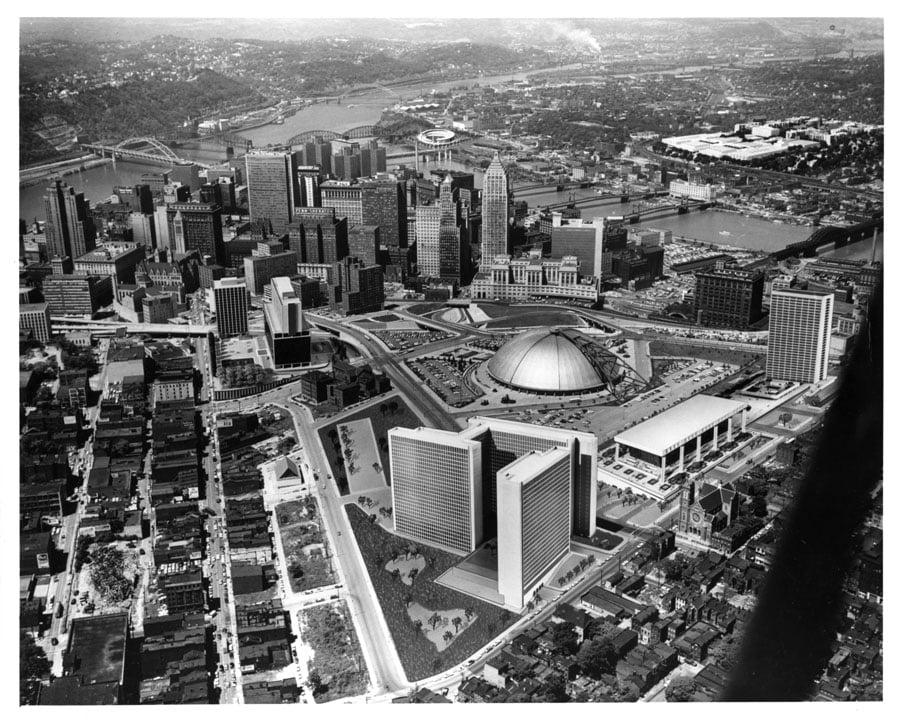

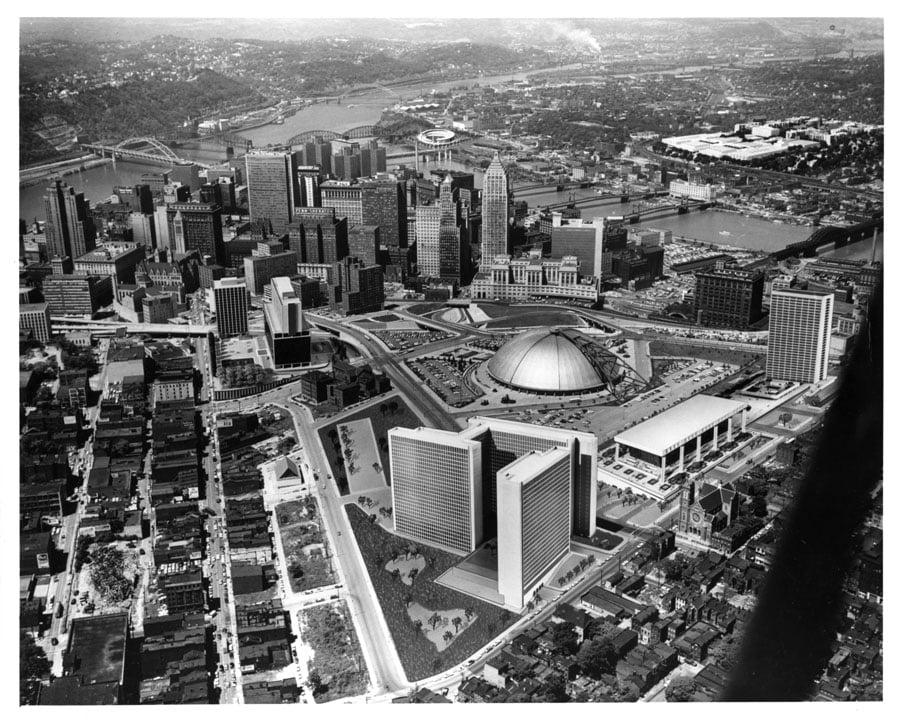

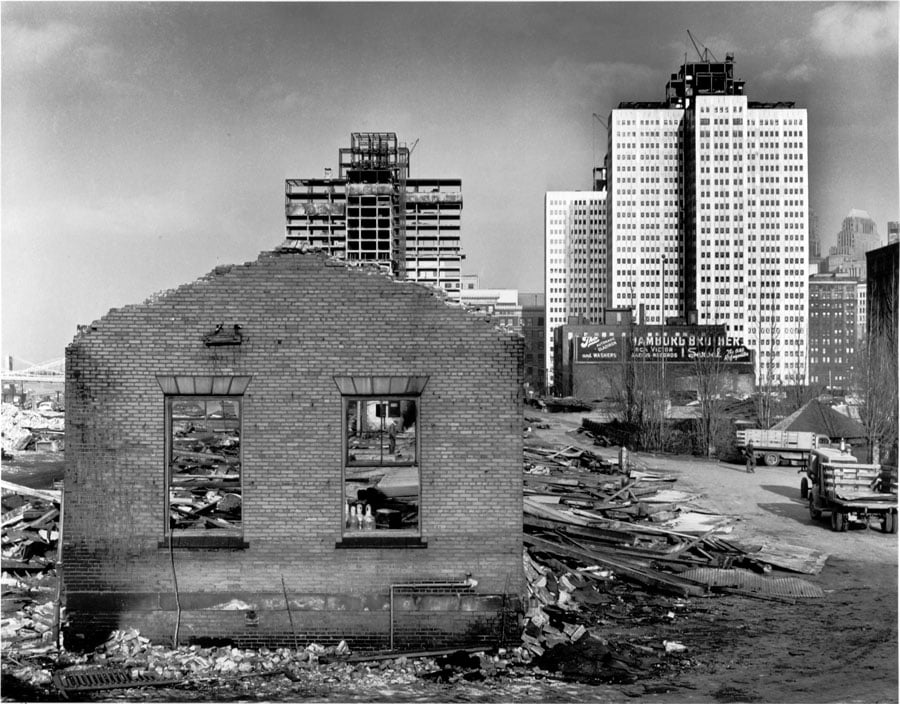

Pittsburgh’s first attempts at renewal were conceived as a necessary program of self-improvement and beautification. Indeed, urban renewal was responsible for creating the literal postcard vision of Pittsburgh’s downtown. What had been a disorderly city fabric blotched by industrial pollution was tamed by rational, Modernist planning. The blithe imagery of crisp office towers and generous recreational spaces was, for once, here brought to convincing realization in a near-unparalleled act of urban scenography: The apron of Point State Park at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers gave way to a downtown proscenium, anchored by new monuments including Gateway Center.

It may have helped that Pittsburgh had a head start. Whereas the Federal Housing Act of 1949 kicked off most large-scale urban renewal, Pittsburgh had by that time already broken ground on the Gateway Center office complex. The Medicis spearheading this renewal were a politician and banker; in fact, Pittsburgh’s foundational renaissance narrative was a bipartisan effort between Democratic Mayor David Lawrence and the Republican financier Richard King Mellon. Corporations, too, played a prominent role in this work, particularly when compared to other large-scale urban renewal projects where government was the overwhelming driver—Boston Government Center being a case in point. (Imagining the Modern’s editors previously documented the architecture of the “new Boston.”) A brochure for Gateway Center extols the “nation’s first comprehensive downtown business redevelopment accomplished without federal aid.”

At a Harvard conference for urban design in 1956, Lawrence stressed the importance of entreating—and not alienating—private actors. The sole politician among the event’s participants (which included planners and academics such as Edmund Bacon, Lewis Mumford, and Victor Gruen), Lawrence generalized his experience and concluded that, “The test of our design, the test of our planning, comes when we make the best possible reconciliation of public powers and controls with the drive and initiative of private enterprise.”

Lawrence might have been selling government short. The city’s most ambitious works of the period necessitated municipal and federal action. Government was surely involved with several neighborhood-level efforts, such as those for Lower Hill and East Liberty, even if it didn’t provide their impetus. The largest projects in the book are closely associated with the names of corporations. The wholesale redevelopment of Allegheny Center, for example, was spearheaded by Alcoa; the redevelopment of the university and cultural district of Oakland by the University of Pittsburgh; and that of the secondary commercial district of East Liberty by local merchants.

Imagining the Modern, which sprang out of an exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 2014, achieves a greater polyphony than such accounts usually do, containing essays, news clippings, archival photography, and promotional materials, which buttress the book’s other contents, namely profiles of key buildings and interviews with their designers. If the predominant sentiment culled from these historical materials is one of sympathy for renewal efforts, dissenting voices are allowed in, particularly in a section concerning the razing of the city’s Allegheny and Lower Hill neighborhoods.

The actual composition of modern architecture in Pittsburgh is recounted in numerous short building profiles. Not all of this work is necessarily good, but a good deal of it is interesting. The initial multitower phase of Gateway Center, for instance, resembles a single superblock of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin, only executed by people with no imagination. Like many renewal plans, its arrangement was pioneering, but its buildings were not.

There are scattered works by singular talents. Mies van der Rohe designed one fine hall at Duquesne University. There is a lonely I.M. Pei tower in the Hill District, a fragment of a much larger scheme. Gordon Bunshaft provided the idea for a pedestrian bridge running under a highway at Point State Park, an extremely graceful work of infrastructure mostly obscured from view. Bunshaft also designed two excellent buildings for the H.J. Heinz factory complex, both unfortunately defaced. There’s a 1961 bank branch by SOM, superb. The New Orleans firm of Curtis and Davis, best known for designing the Superdome, achieved a marvelous diagonal load-bearing exoskeleton for the IBM (now U.S. Steelworkers) Building at Gateway Center. Edward Larrabee Barnes’s Carnegie Museum of Art, meanwhile, is not particularly dramatic but it is an extremely elegant and effective exhibition space all the same.

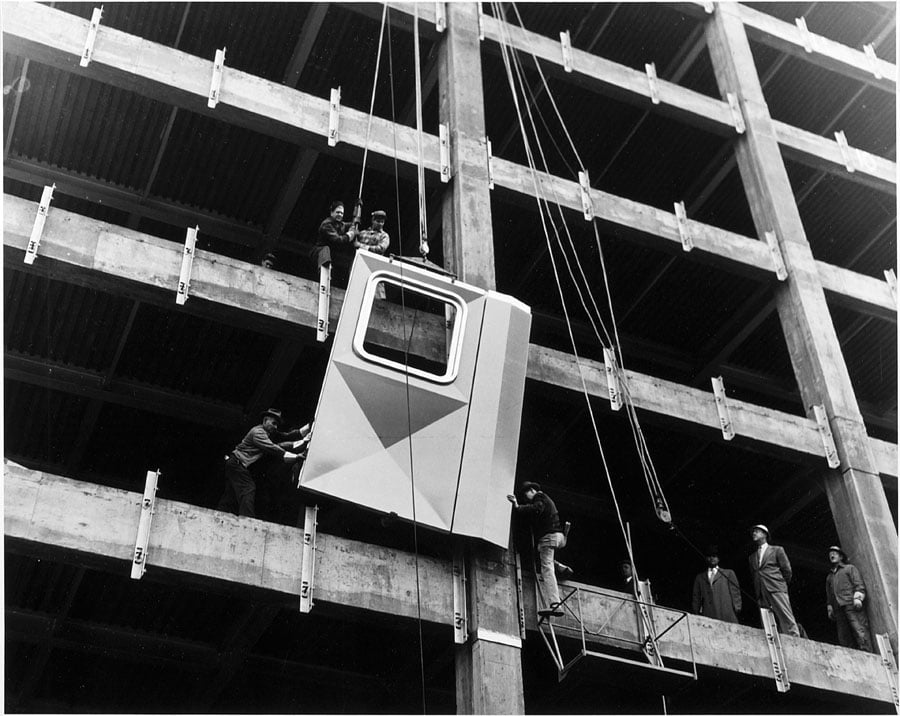

But none of these offices approached the plentitude of Harrison & Abramowitz. The New York firm produced designs for several local corporate giants, including Alcoa and U.S. Steel, and successfully cultivated multiple designs that doubled as advertisements. As the editors note in the book’s introduction, these buildings were individual “essays in developing a corporate expression by pushing the boundaries of what was technologically possible for the industrial materials associated with each entity.” The Alcoa tower, for example, was the first high-rise ever to be clad in stamped aluminum panels, and also featured aluminum wiring, plumbing, heating and cooling, and even blinds. It’s a practice that the firm repeated a few blocks away at 601 Grant Street, and also in Dallas with the aluminum-paneled Republic Tower and in New York (although in stamped steel) with the Socony-Mobil Building.

The U.S. Steel Building was also a highly impressive exercise in steel construction. Its Cor-Ten cladding was a self-sealing and practical patina, and its triangular shape a nimble solution to deflect wind pressures. The design is unusual, with six structural columns offset almost three feet from each facade bearing the building’s weight. These connect to a floor slab at every third story. As the building entry sums up, “The extended slabs connect to the building’s core and in turn support two stories each, effectively making a stack of linked three-story buildings.

Local talent was more uneven in quality. Mitchell & Ritchey built more than any of its peers, and some of its work was even good: the Civic Arena (now gone) or the cylindrical Litchfield Towers at the University of Pittsburgh. Much of it, like Three Rivers Arena (gone) or the firm’s work at Allegheny Center, was merely adequate. Another local office Altenhof and Brown was even more wide of the mark, notwithstanding its thrilling Smithfield Liberty Garage, one of the most-photographed of Pittsburgh’s modern structures.

Tasso Katselas is the one great unsung talent of Pittsburgh’s urban renewal era, and one of its few living protagonists. His corpus was Corbusian at the start but later developed into an unmistakably personal trademark—combinations of brick and concrete, with either as the load-bearing element; fondness for curves and ramps; inclination toward fanciful fenestration. The St. Vincent Monastery (1969) is a fine synopsis of the style.

Where city designers fell short at the building scale, they excelled at the level of landscape. Simonds and Simonds’ superb work is the subject of an essay and numerous project profiles. The office’s elegant Mellon Square was, according to Imagining the Modern’s introduction, “the first integrated design of a modern park above a garage,” and its landscaping at the Equitable Plaza adjacent to Gateway Center is very good.

A curious legacy of Pittsburgh’s renaissance, the editors note, is that the most intensely corporate structures have aged well and are the best liked products of the era among the public, even as they remain generally inaccessible save to employees. Meanwhile, the public works have either been demolished or are regarded with suspicion. This makes a fair amount of sense; the corporate headquarters tend to fit well into their surroundings, while the sporting facilities or shopping megastructures tended not to. Allegheny Center, the largest of these projects, has been desolate for decades, only returning to some life in the last few years (a process which involved tearing out the modern plaza at its center). And with the loss of Civic Arena, the Hill District is a vast parking lot, awaiting city plans to reconnect it to the urban fabric.

The East Liberty redevelopment wasn’t especially destructive, even as it pursued a foolhardy pedestrianization and ring-road scheme. This fact is now evident in how much of the neighborhood’s architecture was preserved. Unfortunately every single trace of Katselas’s very interesting public housing in the neighborhood has been razed.

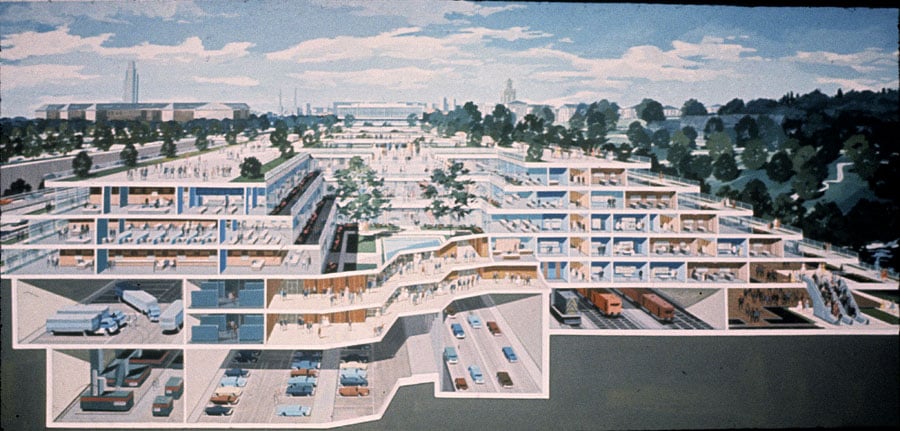

Perhaps the book’s most fascinating chapter is a section which gathers the patently ridiculous unbuilt proposals from a period of “big” thinking. With its elephantine proportions, Wright’s Point proposal from 1948 was “a paean to vehicular infatuation,” but, the editors write, it “utterly failed to meet the client’s expectations and was both structurally dubious and wildly beyond budget.” In a similar Brobgignagian spirit, in 1963 Harrison & Abramowitz proposed an eight-story academic and office structure to fill the Panther Hollow Ravine in the city’s Oakland neighborhood. The plan was almost a mile long: It’s no surprise the ravine stands empty. The feasibility of these plans was perhaps beside the point, and the editors note how architects “employed drawings and models to imagine dramatic, large-scale infrastructures for urban and social transformation.”

Buildings are only part of this story, however, with the book touching upon a broader world of design and advertisement encompassing Paul Rand, Eliot Noyes, and local designer Peter Muller-Monk. There’s also excellent photography from those you would expect: Ezra Stoller, Balthazar Korab, Joseph Molitor, and many more. In Pittsburgh, the modern was amply imagined, and some of it was even built.

You may also enjoy “Planning For (In)Justice: Toni Griffin’s Mission to Foster Equitable Cities.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]