June 7, 2023

“Norman Foster” Show in Paris Celebrates Architecture for the Powerful

In retrospect it was probably inevitable that Steve Jobs, searching in 2009 for an architect to design the new Apple headquarters in Cupertino, would pick Norman Foster. It was not just that the two men, the Bay Area tech giant in his mid-50s and the British architect two decades older, shared a minimalist aesthetic and a perfectionism bordering on the maniacal (not to mention a fondness for black turtlenecks). In a fundamental sense Foster’s entire professional trajectory had bent toward the moment when Jobs, already sick with the pancreatic cancer that would kill him two years later, phoned him to say, “Hi Norman. I need some help.”

As a massive new exhibition on Foster’s work at the Centre Pompidou in Paris makes clear, the worldview reflected by his architecture, reduced to its essence, is very close in spirit to the techno-optimistic Silicon Valley belief system that birthed Jobs—to what Richard Barbook and Andy Cameron, in their 1995 essay The Californian Ideology, dubbed “dotcom neoliberalism.” It is a philosophy built on an unshakeable faith in globalism, growth, and never-ending progress. It is the kind of outlook—as elastic as it is hugely ambitious, mixing elements of the philosophies of Buckminster Fuller, Rachel Carson, Stewart Brand, and Ian McHarg—that allows Foster to call himself a leader of the sustainability movement while continuing to design airports, among the building types most vilified by climate activists, around the globe.

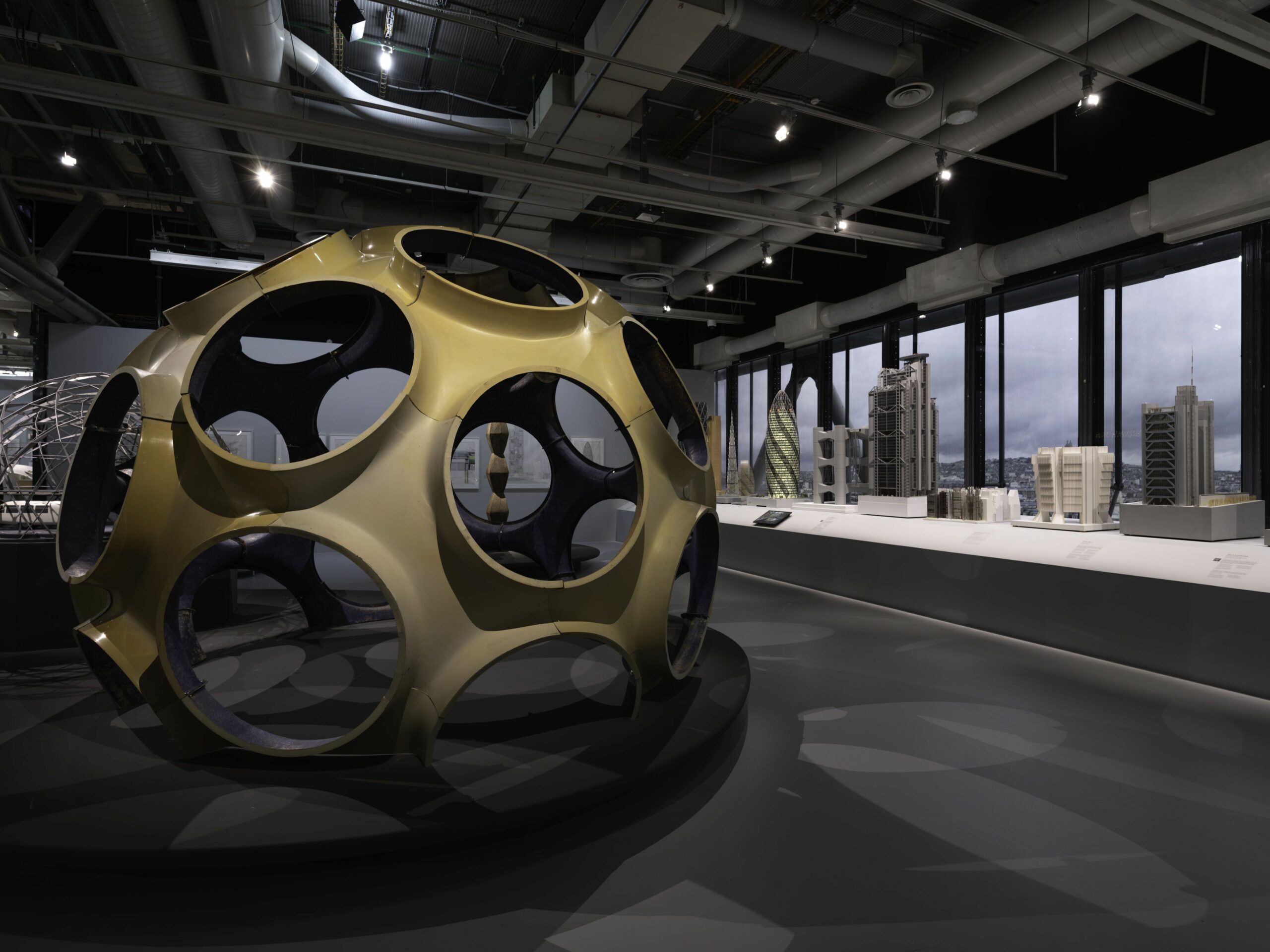

The Pompidou show, which covers much of the museum’s top floor, is called simply “Norman Foster”—more on the title later—and ranks among the most beautiful architecture exhibitions that I have seen in a long while. (The curator is Frédéric Migayrou.) All the greatest hits are here: London’s Stansted Airport (where Foster’s firm, by sinking the utilities below ground, freed the ceiling for a dramatic series of skylights); HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong (which performed a similarly ingenious reimagination of the skyscraper form, moving the structural core from the center of the building to its perimeter and in the process opening up remarkable interior views); the Reichstag in Berlin (where the architect added a glass dome with pedestrian walkways atop the German parliament building, turning an imposing landmark of Nazism into a symbol of democratic participation); and the Millau Viaduct in Southern France, arguably this century’s most photographed work of infrastructure.

The Apple headquarters, officially called “Apple Park,” is featured in a display including two large models as well as a grid of 15 site plans suggesting that Foster’s office, before settling on the donut form, considered hub-and-spoke and amoeba-like versions, among other options. The wall text does not pause to mention what has become by now a familiar critique: that the building’s circular form, inward-looking posture, and heavy reliance on private car parking (11,000 spaces altogether) allow it to stand almost entirely aloof from the metropolitan region around it. If there is one conspicuous absence in the show it is the Khan Shatyr Center in Astana, Kazakhstan, a high-end, tent-shaped mall built for the country’s autocratic ruler, Nursultan Nazarbayev, and unveiled on his 70th birthday in 2010.

Throughout the exhibition, framed drawings of key projects are paired with giant, exquisite models that are, miraculously, left uncovered. Also on view are objects that inspired Foster at some point in his life or career, which is why reaching the row of models of the firm’s most notable office towers requires passing a replica of Fuller’s sleek Dymaxion car #4 and a muscular Boccioni bronze.

The question is what it all adds up to. What are we to make of a giant museum show that is dedicated not to the output of a well-established megafirm, which over the years has employed as many as 1,400 architects, but instead in large part to the persona of its celebrity founder? How do the 171 partners in “Foster + Partners” feel about being left out even of the title of the exhibition? (I suspect they were not surprised.) Is this a last gasp of an era or—given that the Royal Academy Museum in London will be mounting a tribute to Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron beginning July 14—does it represent the first stirrings of a starchitecture revival that nobody asked for?

In certain ways the exhibition is an echo of the Pompidou’s 2014 tribute to Frank Gehry, also organized by Migayrou. But Foster is a special case, the product of a set of conditions in architecture and the wider culture that are not likely to repeat themselves. He and his partners had by 1995 or so cannily positioned themselves like no other firm to take advantage of globalization, urbanization, and the rise of China and the tech industry.

How did they do it? The answer has more do to with class than the exhibition or its catalogue lets on. Foster grew up in a working-class section of Manchester before studying at Yale with Paul Rudolph and Serge Chermayeff and forming an early partnership with his Yale classmate Richard Rogers (who of course would go on to design the Pompidou in a one-off collaboration with Renzo Piano). Both with Rogers and once he started his own office, in 1967, Foster focused on developing an expertise in industrial buildings, in part because as an architect lacking social and political connections—his father was a factory worker and his mother a waitress—he felt that path would be more open to him than chasing private houses and museum commissions.

At the same time, heavily influenced by systems thinking and experiments in modular construction, and by the California modernism of Craig Ellwood and Charles and Ray Eames, he carefully organized his office around an integrated, holistic approach to design. The result was a firm that, as Deyan Sudjic has pointed out, came quickly to resemble “a global research-based consultancy” as much as a high-design architecture office. Foster’s pitch to clients in those key early and middle years had mostly to do with tireless competence and full-service design expertise. The sheen of virtuosity—what led Paul Goldberger, in The New Yorker, to call Foster “the Mozart of Modernism” in 2015—came later, as did those museum and other high-culture commissions he had declined even to pursue when he was starting out.

In recent decades this approach has played especially well with clients who are generally conservative, too cautious about budgets and construction timelines to go with somebody like Gehry, but also understand the power of photogenic architecture to boost the brand, whether the brand is the Hearst media empire or an up-and-coming post-Soviet oligarchy. And it has left Foster, as he looks ahead to his 90th birthday two years from now, in a category all his own (or at the very least one shared only with Denmark’s 48-year-old Bjarke Ingels, who in terms of career arc seems his most obvious heir): the starchitect who outlasted the death of starchitecture to maintain his position as the favored choice of bankers, museum boards, authoritarians, and bureaucrats alike, to say nothing of Silicon Valley dreamers who, on very rare occasions, are willing to admit that they need some help.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

- No tags selected

Latest

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Projects

MAD Architects’ FENIX is the World’s First Art Museum Dedicated to Migration

Located in Rotterdam, FENIX is also the Beijing-based firm’s first European museum project.

Products

Discover the Winners of the METROPOLISLikes 2025 Awards

This year’s product releases at NeoCon and Design Days signal a transformation in interior design.