October 11, 2019

Deconstructing Degrowth at the Oslo Architecture Triennale

The 2019 edition of the triennale imagines a world free from the pursuit of GDP—but is it enough?

“A rising tide lifts all boats” is a phrase that may be familiar to many in the United States. First coined by John F. Kennedy and furthered by Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, it’s predicated on the notion that economic growth benefits everyone. Nothing wrong with that, right? For centuries, economic growth has been the barometer of nation-state success, dating back to the mid-1600s. Today, improving GDP—Gross Domestic Product—is the ultimate goal.

Or is it? Growth is measured by spending in the economy and because of that, unsavory activities can contribute to it. Going to war improves GDP, as can natural disasters. Replacing your smartphone contributes to GDP growth as does knocking down a building and constructing a new one. Conversely, sharing and repairing goods and resources is a GDP sap. Those living in the developed world (who make up the majority of this readership) are already acutely aware that we consume too much—pricking our conscious enough to maybe opt for a paper straw or against a plastic bag.

“Enough” is the key word here—and it’s also the title of the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale (OAT), which this year is centered on the idea of degrowth.

Degrowth isn’t a madcap hippie idea, nor is it new. It can be traced back to Henry David Thoreau but the idea came to the fore in 1972 with the publication of the book The Limits to Growth. Almost 50 years on, eschewing economic expansion is slowly becoming mainstream: New Zealand now prioritizes markers such as health and wellbeing over GDP and, as of this month, even Banksy has his sights set on GDP. Meanwhile, the European Union has recently unveiled a new policy stipulating that household items must be sustainable and spare parts available for a minimum of ten years.

“Enough is enough for endless growth,” demanded British architect Maria Smith at the show’s opening last week. Alongside her were fellow compatriot Phineas Harper, Canadian architect Matthew Dalziel, and Norwegian researcher and artist Cecelie Sachs Olsen—the Triennale’s curators. “It’s time for enough for all.”

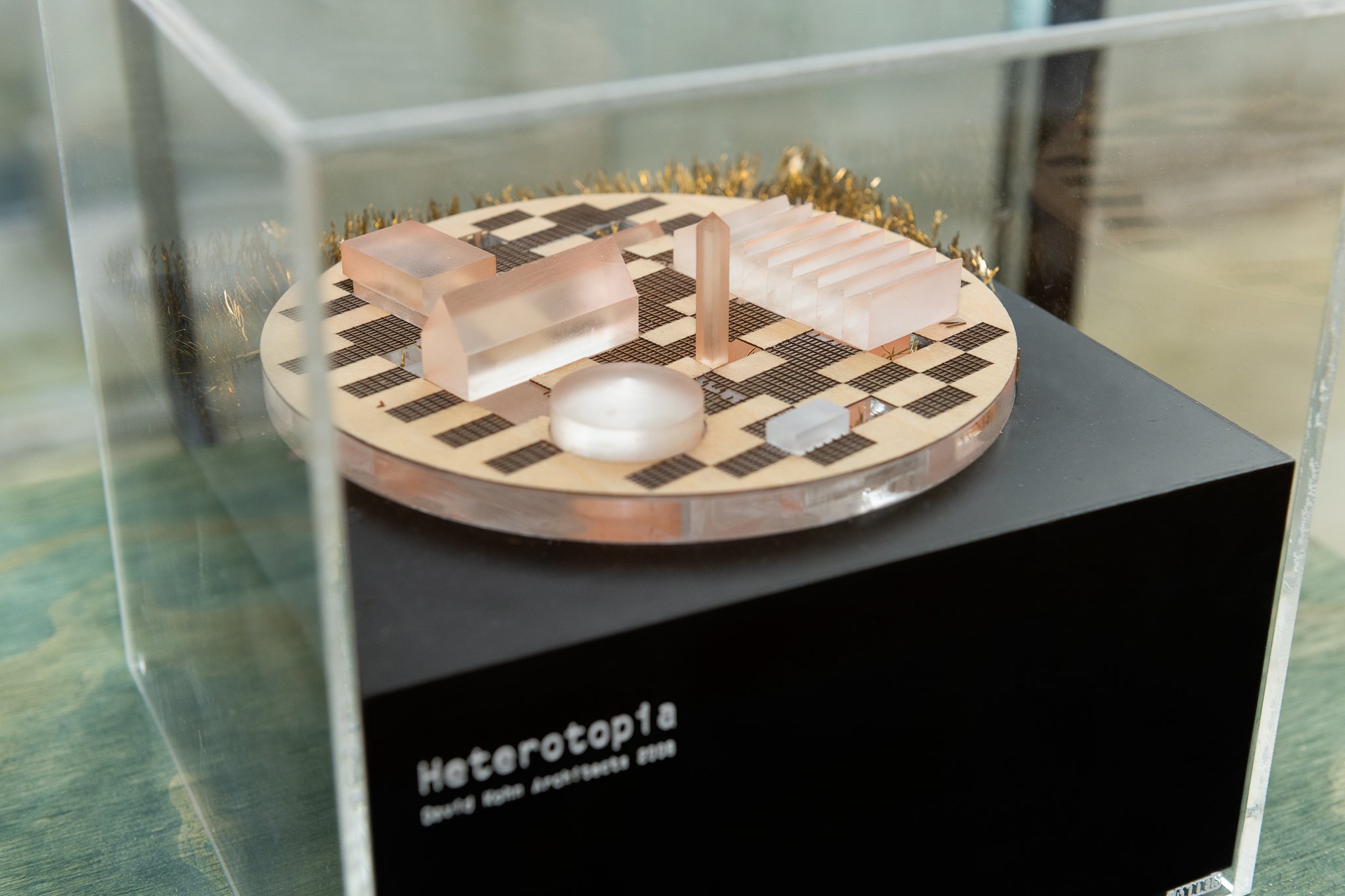

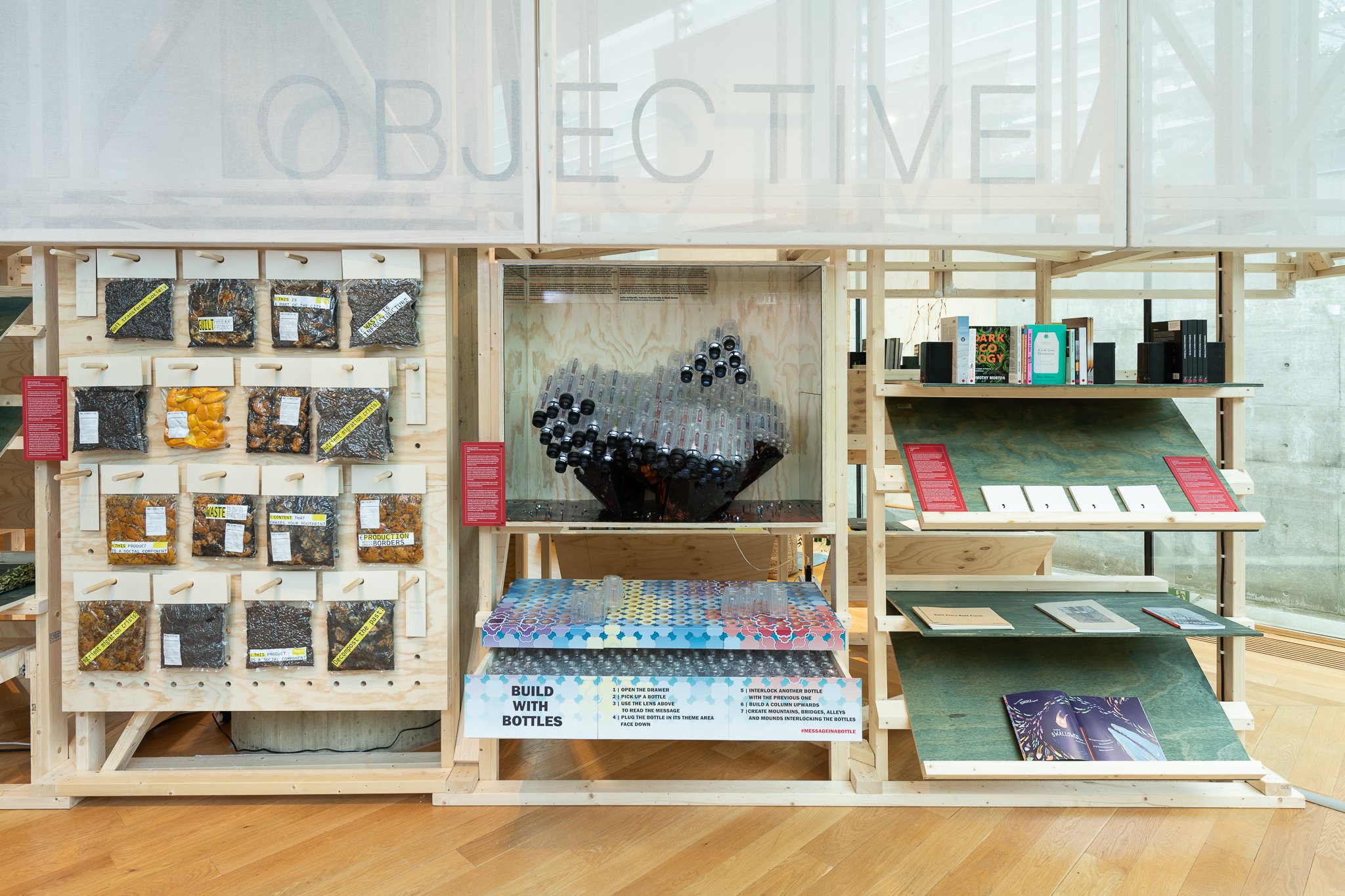

So where do architects fit into all this? This is an architecture triennale, after all. The expected tropes of sustainable approaches to construction are, of course, rolled out, most within what the OAT has called a “Library,” where a collection of texts, board games, and installations have been housed inside the National Museum for Architecture. Libraries, thanks to their sharing capabilities, are the natural nemeses to GDP but the typology is celebrated in Norway, which has a library of the year award. (How many countries can boast that?) At OAT, the idea of sharing is hammered home: Beyond books, there are free-to-borrow skateboards and shared experiences to be had. A vacuum cleaner from British studio EDIT by example, requires three people to use it—democratizing domestic labor which is usually carried out alone.

The OAT spreads across other parts of the city, too. At the “ROM for Art and Architecture” audio tours of the city known as Place Listening are hosted; and at Design & Architecture Norway (DOGA), Factory of the Future has been installed.

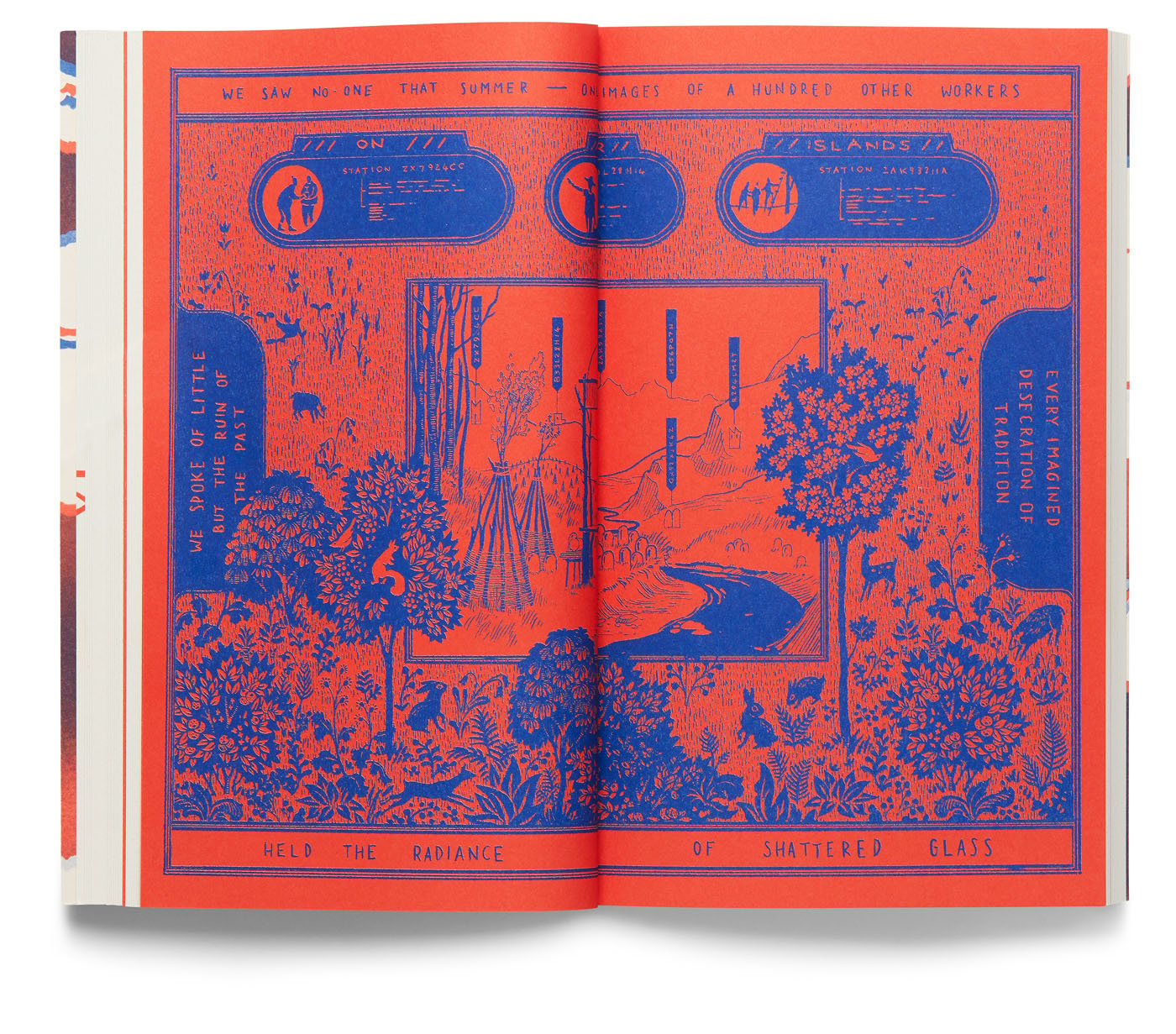

Most interesting, however, is that almost all of what’s on show imagines a different society, one that doesn’t worship productivity and GDP. “Before you build a better world you need to imagine it,” writes Harper in the OAT’s official publication Gross Ideas, which incidentally is a collection of short stories rather than a catalog.

True to the party line, theater plays a role at the Triennale. Rimini Protokoll: Society under Construction, on show at the Oslo National Theater, sees audiences play an active part in a construction project. Likewise, the Place Listening project encourages participants to engage the city in unorthodox ways, chiefly by playing games and going on an audio-guided tour that walks people backwards through Oslo. “What if the focus of urban living was not productivity, but play?” Olsen, who has a background in theater, told Metropolis.

As architecture festivals go, Enough is arguably one of the most physically engaging and it’s better for it too. “We wanted it to be something that wasn’t a book on a wall,” said Smith. “There are so many exhibitions and biennales and triennales; it’s difficult to stand out. And it’s exhausting to take it all in. We aimed for this to be broadly accessible and engaging immediately.”

Physical engagement has benefits beyond simply being fun, though. It’s easy to be a detached observer, but as Olsen says, when you play, you become an active participant. This ethos riffs on the idea that humans currently see ourselves outside of nature, rather than as a part of it. A degrowth world, as the Triennale postulates, is one where we work with the planet as part of a symbiotic relationship, instead of using it as a resource. Case in point: Milan-based GISTO studio proposes reversing the design process. It argues that architects should start designing by seeing what they can do with the materials available rather than scouring the planet for them later on.

It is already well known that using local resources, be it existing materials or existing buildings, is key to a more sustainable future. (Sadly it’s necessary that this still has to be repeated). But such an approach can be uncomfortably close to protectionism and, subsequently, nationalism. The Triennale doesn’t touch on this and therefore struggles to stretch beyond its own borders—most of what’s on show focuses on Europe and not places outside a convenient Global North existence, where our impact on the environment has the biggest consequences.

Besides that, degrowth’s relevance to the built environment is duly clarified by the Triennale. The festival doesn’t intend to provide an ultimate solution: some ideas on show will stick, others won’t. Maybe none of them will. But that’s OK. The profession of the built environment is still better for it, for they at least attempt to provide a platform on which others can build and develop.

As a result, the Triennale is proof that experimentation fuelled by radical imagination can be an enriching exercise—one thinks of how the seminal exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2010, This is Tomorrow, proved to be the springboard for the Smithsons, Eduardo Paolozzi, James Stirling, and Erno Goldfinger among others, all who were conceptually energized by the prompt of of imagining the future.

As the saying goes, “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” as the plethora of disaster movies out there demonstrates. But Enough isn’t a patronizing, doom-and-gloom lecture on the end times, or why we need to be better humans. Somehow, it manages to be a feel-good festival of optimism.

“We don’t sleep to dream but to be productive the next day,” laments Olsen. Indeed, the task of dreaming up the architecture of a society not hellbent on the pursuit GDP is clearly liberating for designers and has made the case that we should probe them to imagine alternative futures. At the risk of being accused of exhibiting disengaged fantasy projects, the OAT is a refreshing departure from the mainstream growth paradigm. The concept of degrowth may seem a bit pie sky to some, but, if we are to keep this planet usable for future generations then it’s a concept worth certainly worth considering and the OAT is a step in the right direction for this way of thinking.

Enough: The Architecture of Degrowth runs through November 24. A full calendar of events can be found here.

You may also enjoy “What Not to Miss at Archtober 2019.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]