March 3, 2022

In Raleigh, an Exhibition Pays Tribute to Phil Freelon’s Prolific Career

“The more we got to know him, the more we realized how absolutely amazing his work was,” Makas says. “He hasn’t gotten the scholarly attention he deserves—and that was an opening for us.”

The exhibition is a critical exploration of Freelon’s drive to articulate and define the African American identity. “It gets across the prolific nature of his practice and the progression of his work over time,” says Zena Howard, who succeeded Freelon at Perkins&Will North Carolina. “You can see the arc of his career and what he was thinking as he practiced.”

The projects designed by The Freelon Group—and later, Perkins&Will—span American cities coast-to-coast. Most, designed from 1991 to 2017, are included in an exhibition that’s broken down into three categories for Freelon’s work: Roots, Skin, and Ideas.

“Skin has a double meaning as cladding and race, and Roots is about connecting to community neighborhoods and Africa,” Makas says. “Ideas is about looking at the ascension and uplift that we see in his work frequently.”

Among the projects included are the Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture in Baltimore (2005), the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco (2005), the International Civil Rights Center in Greensboro (2010), the National Center for Civil & Human Rights in Atlanta (2014), and the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum in Jackson (2017).

Many are depicted in masterful hand sketches and telling photographs; some feature a progressive series of models. Each design is different, because Freelon believed architecture should reflect a deep engagement with the community it serves. “He would say on occasion that he didn’t want to be categorized stylistically or with a certain architectural aesthetic, like Graves or Gehry,” Howard says.

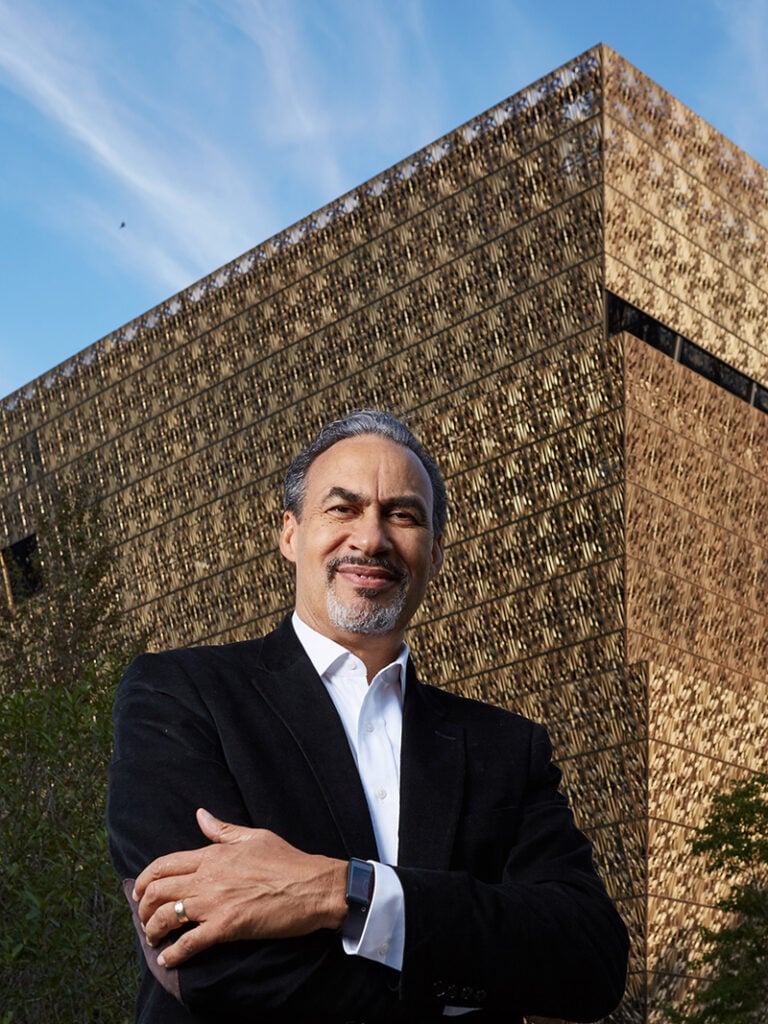

The Freelon Group was named architect of record for the Smithsonian’s African American Museum of History and Culture in 2009, and worked alongside Adjaye Associates, Davis Brody Bond and SmithGroup to create the award-winning museum on the Mall. “The Freelon Group signed and sealed everything,” she says.

Also included in the exhibition —which closes May 15—are the Motown Museum in Detroit, now under construction, and Freedom Park in downtown Raleigh. It’s slated to open later this year, across the street from the North Carolina Legislative Building.

To be sure, Freedom Park will leave a lasting legacy for the architect. But Freelon’s real legacy lies with the young architects he mentored, nurtured, and supported while he was alive—and those who feel his influence today. “Being Black, female, and in architecture, studying him made me feel like what I’m doing matters,” Sierra Grant, a graduate student at UNCC who helped research the exhibition, says. “I can inspire people, just by existing.”

That’s precisely the message Phil Freelon wanted to send.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Breland–Harper Mines the Past to Design a Better Future

In less than a decade, Ireland-Harper, the Los Angeles–based studio has completed over 100 adaptive reuse projects.

Products

How the Furniture Industry is Stepping Up on Circularity

Responding to new studies on the environmental impact of furniture, manufacturers, dealers, and start-ups are accelerating their carbon and circularity initiatives.

Viewpoints

The 2024 Net Zero Conference Highlights the Importance of Collective Action

Last month, leading climate experts convened at the Anaheim Convention Center to reenvision the built environment for a net zero future.