January 6, 2020

If You Are Serious About Sustainability, Social Equity Can’t Be Just Another Add-On

Social impact was supposed to be central to sustainability from the start. What happened?

In August 2018, the NAACP announced Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector, an initiative that addresses an uncomfortable truth: Sustainable design is increasingly a luxury commodity.

“Communities of color and low income communities bear the brunt of the impacts of unhealthy, energy inefficient, and disaster vulnerable buildings,” reads the NAACP’s statement. “Yet, as one looks around the tables or worksites of the sustainable and regenerative building sector, there is little representation of the populations most impacted by our current proliferation of unsustainable, inefficient, sometimes unsafe, and often unhealthy building stock.”

Heather Rosenberg, an associate principal at Arup and a leader in resilience planning in Southern California, puts it more bluntly: “You can get a green certification and be displacing a community.”

Social equity—and positive social impact more generally—was supposed to be central to sustainability from the start. In the 1990s, the decade that saw the rise of BREEAM and the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), John Elkington, an entrepreneur and author on corporate responsibility, coined the “triple bottom line”: sustainability for people, the environment, and the economy. Elkington has since expressed regret that the social part of the equation has fallen by the wayside. “Success or failure on sustainability goals…must also be measured in terms of the wellbeing of billions of people,” he wrote in Harvard Business Review last year. “[The] sustainability sector’s record in moving the needle on those goals has been decidedly mixed.”

Among the reasons why are the complexities of how to define equity within social impact, let alone trace the influence of a building upon it. Unlike determining an environmental footprint, which can be measured in cubic tons or parts per million, considering social impact draws on sociology, psychology, economics, and medicine. It requires thinking on three scales: the physical life cycle of a project, including materials and construction; its ripple effects within its context, like a neighborhood or city, as well as across time; and its more tightly bounded cycles of building occupancy. These three loops, in turn, touch distinct population groups: building users and occupants; those working in construction and installation; neighborhoods; and people involved in the building-material supply chain.

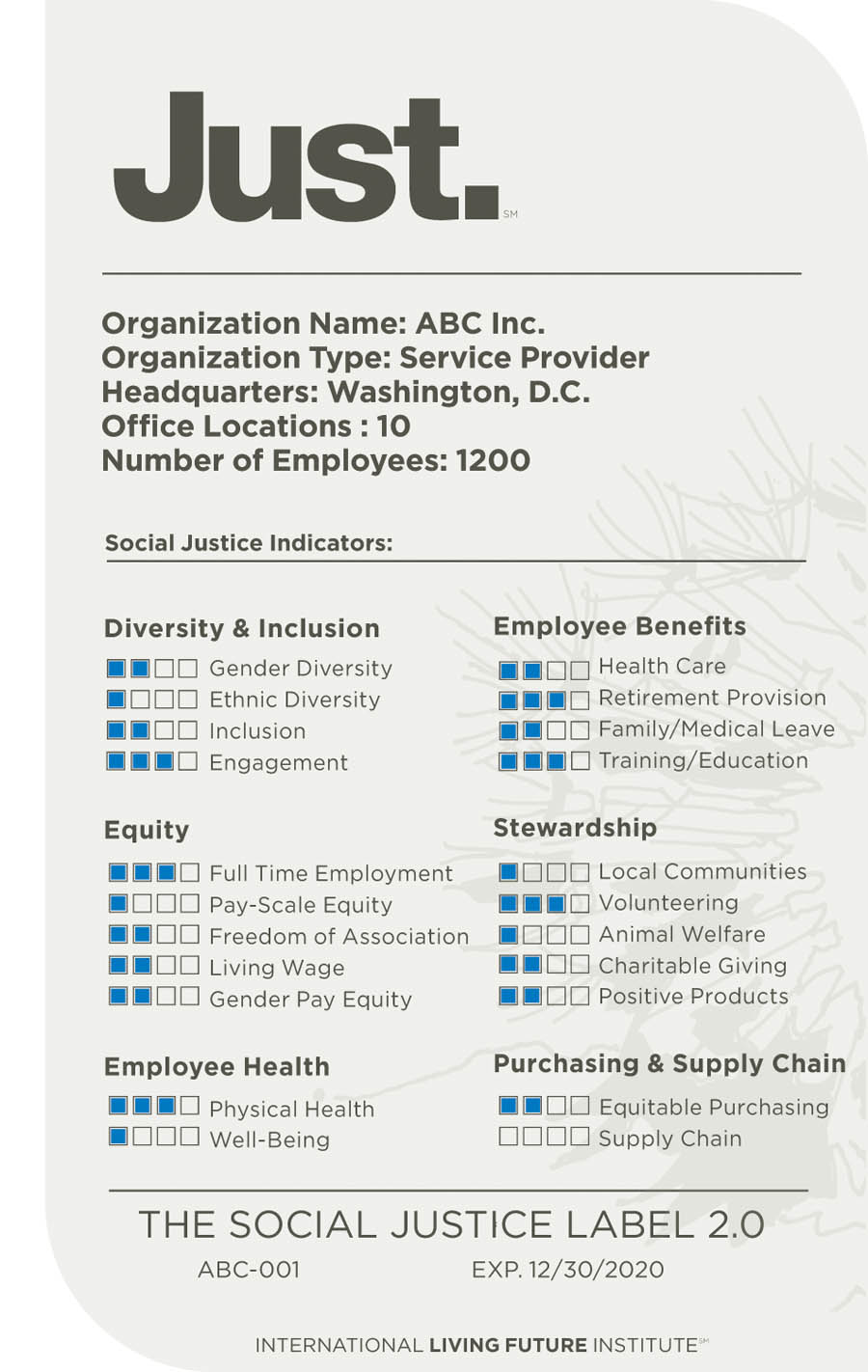

As major project-level rating systems like LEED have gained prominence and become shorthand for “sustainable design,” they’ve put increased emphasis on equity, albeit with varying degrees of specificity. The International Living Future Institute Living Building Challenge was the first and remains the only major green label to require social equity considerations, period. Its imperatives are explicit in ways that equity considerations in other standards are not. The requirement for universal access, for instance, states that all projects must make “all primary transportation, roads and non-building infrastructure…equally accessible to all members of the public regardless of background, age and socioeconomic class—including the homeless.” Compliance with the Seven Principles of Universal Design, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), or the Architectural Barriers Act is nonnegotiable.

Within LEED, credits that directly speak to social equity remain optional—but there are some alternatives. In 2014, following a report by a special working group, LEED introduced three pilot credits to its Building Design and Construction program: One rewards projects that identify and address community needs and disparities; a second rewards equitable practices by owners, architects, engineers, and contractors; and a third calls for supply chain assessments, particularly targeting human rights violations. WELL, meanwhile, is arguably the most obvious system in which to discuss social impact, given its focus on human health and well-being, and its most recent version intends to make “an organization’s ability to level the playing field…fundamental to the [WELL rating] system itself,” says Rachel Gutter, president of the International WELL Building Institute. This has meant introducing three community preconditions to WELL v2, which advocate collaborative design and community-minded practices within the workplace, like providing “easily accessible” wellness education. It is hard to miss, however, that universal design and equitable bathroom accommodations are “optimizations,” not “preconditions,” under WELL v2.

It makes sense that sustainability rating systems allow for some variation, considering that social impact depends on each project’s unique players, site, and history. But it also follows that what “equity” means within these scales is subjective, self-selecting, and, as with sustainability ratings in general, often based on checklist systems that prioritize process over results. These put an emphasis on community engagement during brief formation and the design process, and look for added benefits—like opening outdoor space to public use, installing ADA-compliant egress on city land, or creating philanthropic programs—rather than ask projects to measure and prove the absence of negative impact.

Projects pursuing LEED’s Social Equity within the Community credit must complete two portions of the Social Economic Environmental Design (SEED) Network evaluation—a rigorous tool for assessing the social, economic, and environmental impact of design projects—or partner with community service or advocacy groups, but there is no requirement as to what the outcome of that partnership might be. For those pursuing its Social Equity within the Project Team credit, there are multiple routes: paying wages and benefits that meet or exceed the requirements of the federal Davis-Bacon Act, participating in workforce development training, or demonstrating corporate social responsibility through other certifications, to name a few.

“If you look at LEED’s first pilot, it was easier than it is now,” reflects Susan Kaplan, who chaired the USGBC’s Social Equity Working Group. “If you know about your diversity levels or pay disparity, because you have to report it, then you can’t ignore it so easily.”

The emphasis that sustainability rating systems put on process often means they rely on third-party mechanisms like the SEED Network’s Evaluator process and Enterprise Green Communities’ Criteria Checklist for low-income housing, which requires, among other things, an evaluation of access to public transportation and public space, and community wealth creation. These organizations have established themselves as experts in tracking community-driven work and provide rubrics and standards of documentation of accessible public meetings, inclusive public outreach, and user interviews that dovetail with the architecture industry’s more marketed systems like the Living Building Challenge.

Such processes, however, are above and beyond what most clients want, so the types of projects that seek social impact accountability often have equity in their mission to begin with. Foundations, cities, and nonprofits, for instance, fare well: “[T]hose were the groups that were doing the most interesting things, because [those goals] aligned with the mission,” says Arup’s Rosenberg, who participated in the USGBC’s Social Equity Working Group.

Social impact thinking—particularly at the community level—needs to be introduced in the early stages of forming a design brief, sometimes years before an RFP is even issued. And the power to form a brief that takes equity seriously lies disproportionately with the client, be it a developer, building owner, city agency, nonprofit, or foundation.

Take the Dahlia Campus for Health and Well-Being in the low-income Park Hill neighborhood of Denver, completed in 2015 and designed by Anderson Mason Dale Architects. The brief, which eventually earned LEED Social Equity pilot credits, was shaped by a three-year community engagement effort led by the client, the Mental Health Center of Denver (MHCD). The team’s process—documented with the SEED Evaluator—gained trust from the community and ultimately led to the addition of a number of programs to improve access to fresh food and child care, on top of the initial mental health services program. The community-driven process was so successful, says design principal Cathy Bellem, that Anderson Mason Dale is partnering with the MHCD on another job to help form the design brief in an even more collaborative fashion.

But this kind of client involvement is far from the norm. “If you have a client who’s not interested in [social equity goals], then you’re either just rolling with what their goals are…or you’re being somewhat subversive to try to fit in broader community goals,” says Bellem. “I think a lot of social equity goals oftentimes are only moved forward through what amounts to a volunteer effort [on the part of the architect].”

Even when project teams get on board, there’s the question of account- ability and follow-up after move-in—something that most sustainable certification programs don’t require. Gaining access to post-occupancy surveys, if they’re conducted at all, can be challenging because of change over in project management, and that’s if the client is willing. “We’ve tried to have those conversations [about gaining access to post-occupancy survey data],” says Anthony Brower, director of sustainable design at Gensler and a board director for the USGBC’s Los Angeles chapter. “On one project…we tried writing [survey access] into the contract. It was the first thing the client struck out of the agreement.”

“Everybody wants to be seen as doing the right thing, but it’s the old wolf in sheep’s clothing,” says Mindy Fullilove, a psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health at The New School’s Parsons School of Design. She’s skeptical of the motive underlying the inclusion of social impact within sustainability accreditation, particularly if it remains self-reported, seeing it as trading major community change for a few marketable amenities. In her view, a fundamental weakness is that rating systems fail to ask whether a project should move forward at all. “We’re in a national housing crisis,” she says. “We don’t solve that by green-lighting developers to create more high-end housing.”

Meanwhile, a slew of broader-scaled sustainability rating systems are gaining momentum. Enterprise Green Communities Criteria are now required for all new Department of Housing Preservation and Development projects in New York City. LEED for Neighborhood Development and for Cities and Communities (introduced in 2016) and the WELL Community Standard pilot (introduced in 2017) use the point system at the scale of urban development, though the jury is still out on their effectiveness. And this fall, the Grace Farms Foundation announced an industry working group to look at slavery in the building industry.

Any true accountability around social equity will require looking beyond the architecture office. Angie Brooks, co-principal of Brooks + Scarpa, an L.A.-based firm with an extensive portfolio of social impact work, particularly in housing, urges architects who want to improve equity to become advocates at the city level. “The designing of buildings is one thing,” she says, but “the framework within which we design needs to be fixed.”

Jacqueline Patterson, director of the NAACP’s Environmental and Climate Justice Program, suggests a change in mind-set. “There needs to be a movement towards universalizing access to start with folks who need it most,” she adds. “Equity can’t be an add-on; it actually needs to be foundational.”

You may also enjoy “A New Idea in Architecture? No New Buildings.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]