December 3, 2024

Three Firms Redefining Design Through Community-Led Processes

“Shouldn’t all architecture be humanitarian in some way? Aren’t we making it for humans?”

–Leighton Beaman, cofounder, General Architecture Collaborative

Open Design Collective, General Architecture Collaborative, and Nowhere Collaborative are helping reinvent design practice by creating community-led processes and turning traditional Western design thinking on its head. They center marginalized individuals and women, who are still underrepresented in the design field and often overlooked in decision-making in the built environment. All three firms are sharing power to bring prosperity back to disinvested places and truly change people’s lives.

01. Nowhere Collaborative

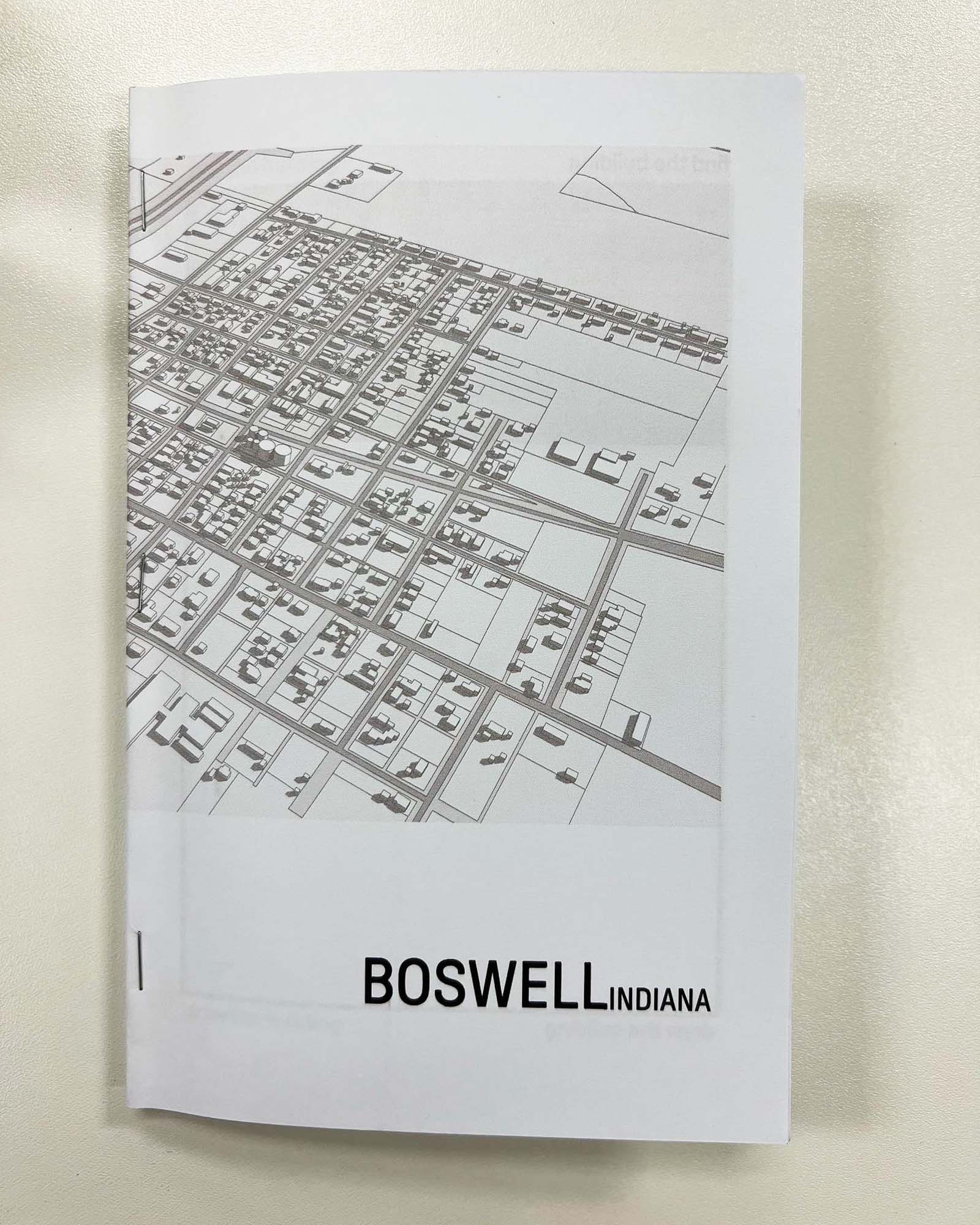

Architect Catherine Baker made the leap from an established firm to transform and be transformed by the rural community of Boswell, Indiana (population 800). Nowhere Collaborative is a one-woman, place-based practice that is intent on addressing issues specific to its community.

Verda Alexander (VA): Tell us about your design journey and why you started Nowhere Collaborative.

Catherine Baker (CB): In college, I was interested in the cultural impact of design, so instead of architecture, I got my graduate degree in social science. My first job was at a firm creating affordable housing. It was rewarding, but I also started to question the top-down funding model and how limiting design solutions were because of it. I wanted to engage with the community in a more thoughtful way.

During the pandemic, my husband and I started spending more time in our tiny farmhouse in rural Indiana than in our apartment in downtown Chicago. These smaller towns have been neglected. You could not even access high-speed internet—and this is just 100 miles outside of Chicago. I saw an opportunity to look at a community that didn’t have the resources that urban areas have.

So, I created Nowhere Collaborative, a place-based firm. It’s not about a typology of architecture but about an actual place—Boswell, Indiana—where there’s been a lot of disinvestment. And if you can make a practice work in a town of 800 in rural Indiana, it could be a model that works almost anywhere.

Maya Bird-Murphy (MBM): What are your design values, and how do you embed them in your practice?

CB: People need good design and architecture. I think creative design-thinking skills are everywhere, not just in urban areas. Communities of disinvestment are everywhere. You can’t assume that because an area is rural there’s a type of person who lives there. The town we’re in is undergoing rapid demographic changes. The rest of the county is 98 percent white, but this town is 30 percent Latinx. There is diversity in these places. We just must be open to seeing and understanding it.

There’s an authenticity here that I hope to project and embody. You might think of Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more,” but I think in this case it’s “do more with less” because you have to be really creative with really tight budgets. I love that challenge. You know there isn’t funding to do a super-high-end detail, but that doesn’t mean you can’t have responsive designs and creative solutions.

VA: Walk us through one of your projects.

CB: I’m currently the only architect in town. I’m working on two projects with the Wabash Economic Growth Alliance (WEGA). WEGA recognized that the lack of quality business spaces in small towns was impeding development, so to support regional growth, it is developing a business incubator and market. One of the projects, The Social Exchange, is the restoration of a historic downtown building that will serve as a business training facility and networking hub with a deli on the ground floor. The second project, The Market, is a new construction in the core of historic downtown that is anchored by a farm store and surrounded by small retail training spaces for dining, food, produce, and craft entrepreneurs. The idea is to create economic development. Once you graduate from the business incubator, you could start renting space in the market and, eventually, grow into a brick-and-mortar space of your own.

You can make these incremental changes in the community that will change people’s perspectives of where they live.

02. Open Design Collective

Vanessa Morrison and Deborah Richards lead Open Design Collective, a nonprofit organization that creates social and spatial change in Oklahoma City through large- and small-scale community-led urban planning, architecture, and design projects. These two women have placed themselves staunchly within the community, working against the negative effects of gentrification and disinvestment that happen in the name of progress in cities like theirs all over America.

MBM: Tell us about your design journey and why you started Open Design Collective.

Vanessa Morrison (VM): I’ve worked over the last 18 years in social services, public health, and trauma and crisis intervention. For me, community service is central to everything I do, and I saw the urban planning profession as a way to be on the preventative side, instead of the reactive, where I could help create, build, and design environments that were healthier.

Deborah Richards (DR): I went to architecture school, but I was always interested in participatory design and engagement. I was interested in learning about how to give people agency in design choices even if they weren’t trained as an architect or a designer. In architecture school, the emphasis was to identify problems and create solutions. We created the wildest solutions that were like whole new worlds. But I found there were problems with this—where were the people? Where were the worlds that are based on existing community assets and knowledge?

VA: What problem are you trying to solve?

VM: Our mission is to support the social and spatial needs of Black and marginalized communities. Everything from urban renewal to redlining to segregation and systemic forms of violence have been inflicted on these communities. It’s important that we don’t repeat those patterns of injustice. As we’re co-creating ideas with community members, we go deep into addressing the historical context and root causes.

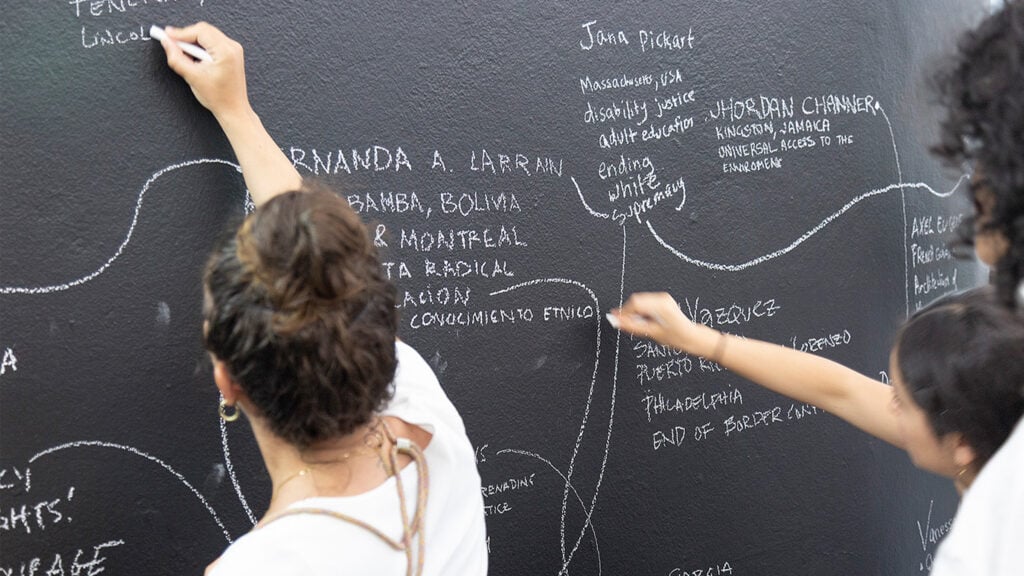

DR: We start at the base level through discussions with community members, identifying the existing skill sets, knowledge, needs, and opportunities. Then we create whole projects around them that incorporate planning, visioning, architecture, and fundraising. We are looking for opportunities to create stronger community networks and build off the legacy of the communities that are already here.

VA: Tell us about one of your favorite projects.

VM: We just secured a $500,000 EPA grant, which is unprecedented for Oklahoma. There’s a small Black-owned business working on an outdoor expansion on an Urban Renewal Authority–owned lot, and we’re designing and building a green space to better connect to the natural environment and strengthen social connections. We’re able to support the ongoing mobilizing efforts of environmental justice issues in this community by having air monitoring systems in the park.

DR: There’s a big issue to overcome in Oklahoma regarding density to support retail. How do we create walkable communities? How do those community connections and proximity strengthen businesses and residential opportunities? So, this process also includes capacity building—allowing people to understand how to talk about these issues and how issues such as density, culture, and inclusion impact their daily lives. This gives them a stronger voice and empowers them to have conversations with the city.

03. General Architecture Collaborative

General Architecture Collaborative (GAC) is a nonprofit organization in New York and a social enterprise in Rwanda that works with individuals, communities, and institutions to create a more equitable world through design, research, and advocacy. They are working to change the top-down model of how development is done in the Global South, where the people getting funds and infrastructure are handily dismissed, continuing old patterns of imperialism. Here’s our conversation with cofounders Yutaka Sho and Leighton Beaman.

VM: Also, how can people in this community be developers, property owners, and a part of building the community up again? How do we preserve the existing assets and make sure that as new development comes in, it’s cohesive and connected to the history that is so strong with this neighborhood, but also designed and built in a way that doesn’t over-encapsulate what’s still here? Now we’re working on an entire northeast Oklahoma City cultural master plan and showing people this work is possible.

VA: Tell us why you started GAC and what led you to Rwanda.

Yutaka Sho (YS): The members of GAC met at the Harvard GSD, and we formed the nonprofit shortly after we graduated. We wanted to use our design agency and advocacy efforts to support people who don’t typically have access to good design.

My design beliefs originated in a food cooperative that my mother used to work for called Seka’s Club in Tokyo. It started in 1968 with 200 members; they now have 300,000 members. They run eldercare facilities, an orphanage, a bank, and whatever the community needs. It’s 90 percent run by housewives. Housewives in Japan are the lowest tier of the social hierarchy. If they can do it, anybody can do it.

When we went to Rwanda, we met with many female-run NGOs, locally founded and operated. Right after the genocide in 1994, 70 percent of the population were women because men were either killed or jailed. Women were not able to own land or businesses, but suddenly they had to take the lead in rebuilding the devastated country and economy. We were interested in how women build, how they make decisions, and what different types of spaces they make. We wanted to support them, but not from a place of charity. We wanted to be equals and collaborate. So that was the beginning, and our test to see if we could run this rickety, precarious practice.

VA: What issues are you hoping to address?

YS: This divide between North and South is a problem in my mind. The Global North fundraises and then sends money to the Global South to do development work. Seventy percent of the federal budget in Rwanda is from foreign aid. Foreign companies come in and lead the development projects, and the end users don’t have much say in how the development money is used. Nobody listens to them because they’re considered to be under-educated and disorganized. We are trying to change how the global development industry is doing business there.

Leighton Beaman (LB): As a designer, you are taught that you have a say over how everything goes because it’s your vision. It takes a little bit of learning to let go and become a coauthor with other people.

For example, in the first earthbags house that we collaborated on, there were parts of the project that were woven by local weavers. They typically make things that are small-scale like a bag or a bowl. In this project, they started to weave entire walls that could roll up and come down to block wind or provide some privacy, and that was a moment I realized this approach was nothing I would have imagined, drawn, detailed, or specified, and it only came into being because a group of people from that community were building the project.

MBM: What impact do you hope to make when you look toward the future?

LB: We’re a sort of design-build firm; we use the entire project process as a catalyst for community change. We leverage the network of NGOs and organizations already in the region to join us in that process. And we’re conscious to not create another relationship of dependence.

YS: We hope to make ourselves obsolete so that we are not needed anymore. It’s kind of ridiculous that sometimes we represent our end users to the donors or the government because our end users are considered not educated or incapable of representing themselves. This is the worst postcolonial power hierarchy that’s being exacerbated.

LB: In the future, [we want it to] be normal to advocate for communities, and to involve people in the process more. It’s like erasing some of the things that define us as being anything other than normal.

VA: I love that. Alternative practice is not alternative anymore.

LB: Yes. In many ways, we are not that alternative. We’re designing things for people. Maybe the process is a little bit different, but one of the things that we get sometimes is like, “Oh, you do humanitarian work?” And it’s like, “Well, shouldn’t all architecture be humanitarian in some way? Aren’t we making it for humans?”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.