June 6, 2017

Urbanist, Marketeer, Horticulturalist: Frank Lloyd Wright Is All These and More at New MoMA Exhibition

Curator Barry Bergdoll breaks down “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive” and explains why he hopes the show will signal a Wrightian renaissance.

For a time there, Barry Bergdoll was having trouble sleeping at night. The Columbia University professor and Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) curator had been asked to mount a brand new exhibit on Frank Lloyd Wright. And while the task would be anxiety-inducing under any circumstances, this one was especially so—Bergdoll had, just a few years prior, in 2014, curated an entire show on Wright. How was he going to make this one distinct?

The answer came suddenly. The new exhibition was meant to celebrate the transfer of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation’s archives to MoMA and Columbia’s Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library. What if this show were about the newly accessible archives themselves? The thought was the seed that eventually became Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Metropolis editor Vanessa Quirk spoke with Bergdoll to learn more about this new exhibit, Wright’s relevance today, and learning to live with the messy contradictions that make Wright Wright.

Vanessa Quirk: How would you have characterized Frank Lloyd Wright’s relevance to architecture and society? Did your conception of Wright change during the course of putting together the exhibition?

Barry Bergdoll: Boy, that’s a good question. Well, you know I’ve been teaching Modern architecture at Columbia for decades, so of course I’ve got the standard and updated review of Frank Lloyd Wright down pat. Frank Lloyd Wright is an extremely rare case of an architect who had as much of a public following as a professional following. He is probably the only architect who’s almost more popular with the general public than he is with architects. That means too that the general outlines of his career are also well-known to a sizable segment of the interested public, so that makes a huge challenge. There was one night I woke up, as I was having anxiety: how could I not make this a predictable show covering Frank Lloyd Wright’s career in a monographic fashion? Even more because it’s only been a handful of years since such a show was mounted at the Guggenheim Museum.

Then, it suddenly occurred to me that I was asking the wrong question. The question is: What is the significance of the presence of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archive—shared between the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia and the Museum of Modern Art—now [being] in New York? Of the accessibility of the collections to scholars to look at materials in Avery, rather than making the pilgrimage to the desert of Arizona?

From that moment, when I realized that the exhibition was as much about the archives as it was about Frank Lloyd Wright per se, came the concept, which is the title of the exhibition: Unpacking the Archive. The basic game plan of the show is 14 people interpreting a key object that they found intriguing and interesting in the archive and thinking about it.

Embracing the contradictions—sometimes seeming contradictions, sometimes open contradictions—in a figure as complex and long-lived, as combative and as consistently inconsistent, and inconsistently consistent as Frank Lloyd Wright, that’s the real thing that moved for me. Rather than trying to create an extremely neat narrative that makes sense, of what we want an artist to be, to have a beginning period, a middle period, and an end period, and to have an evolution that is going in a direction, towards a kind of denouement, embracing some of the contradictions and studying them. Some are the contradictions of an extremely creative mind and unorthodox intellect. Some of them are reflections on the contradictions of America in the late 19th and 20th century. Rather than trying to iron them out, you connect them, and talking about them and understanding them, I suppose is, in the very generous sense, what is newer for me.

I had already done that to a certain extent in the single author show, which was the 2014 show on Frank Lloyd Wright, where I tried to understand how it was that Wright was simultaneously creating, with Broadacre City, a model of dispersed urbanism at practically territorial scale with very low density, and yet at the same time developing project after project for an ever higher tower that seemed to go, literally and figuratively, in the opposite direction.

VQ: What about this caricature of Wright that a lot of people seem to have, this idea of him being an imperious master builder? Is that something that you think is wrong? Or do you think it’s an important element to consider in his life and work?

BB: I think that many people have a love/hate relationship with the idea of arrogance. I suppose the Trump phenomenon is part of it now. There’s an interesting contradiction there. At one point, I wanted to make the whole show about a second contradiction. The first show was about density versus dispersal and this one would be about Frank Lloyd Wright’s cultivation of his own status as a genius and his fascination with creating building systems that untrained individuals could make.

Very early in his career, he designed prefabricated buildings that you could buy from a journal. There were also, of course, the Usonian houses, the textile block system, and what we’ve called the Usonian Automatic system. The creation of these construction systems means that the artistic genius doesn’t create a singular work. Actually he creates a kit of parts, almost the DNA, if you will, of a system that anyone can use to achieve what he thought would be a superior result for housing. So that’s an extremely interesting tension too.

How is this person, who is the forerunner of today’s architects also the person who wants to invent systems which could be used by people who would never need to see him on sites that he would never visit or supervise? That was a really fascinating tension and contradiction. Both the imperious master builder and then a kind of noblesse oblige desire to do something for the common man are equally present in Wright, pulling at one another at any given moment.

VQ: When you spoke to us for a small preview of the exhibition, you told us that each section of the exhibit is as much about the object on display as it is about the interpreter. Could you explain what you meant by that?

BB: Each of the sections represents the thought process, the historical investigation, the interpretation of a particular individual. When you enter each section in the exhibition, you’ll see the object that was chosen that’s being unpacked, and next will be a film of the interpreter in the archives talking to us about how they became intrigued with it, how they went about working with it—it’s riffing off a bit from my Columbia colleague Gwen Wright’s long-running series History Detectives.

I don’t think many people who are not historians or scholars have spent time in an archive, so it’s really presenting to the public: What does it mean to work in an archive? How do you come up with an interpretation from documents? How did the historian work? The exhibition is as much about the activity of research, investigation, exploration, and proposing an interpretation.

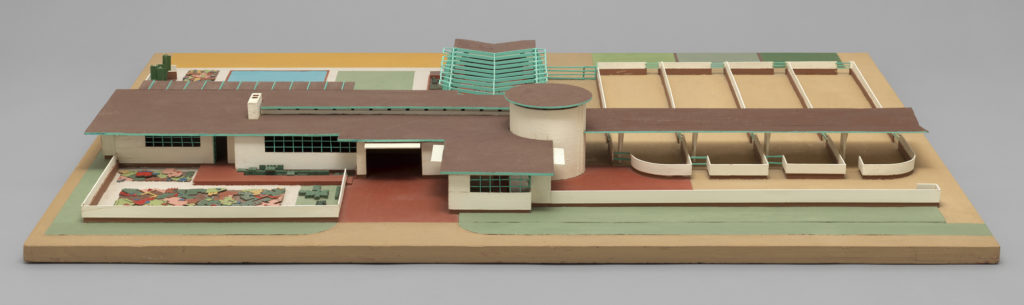

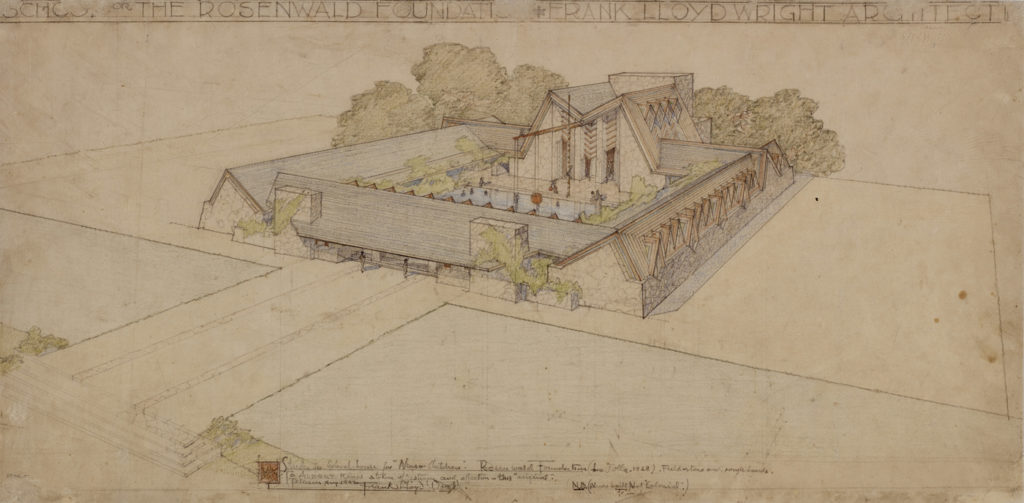

Each one of these interpretations is authored—it’s not the definitive view. It is the view, for example, of Mabel Wilson on Frank Lloyd Wright in relationship to the Rosenwald Foundation and the issue of race and education in America in the 1920s and 1930s. It is my point of view on Frank Lloyd Wright’s relationship to television and an inclusion of a genealogy of engineers on a nearly impossible mile-high skyscraper. It is Therese O’Malley’s opinion on the relationship of Frank Lloyd Wright to the choosing of plant materials and investigations into his relationship with seed companies. So on and so forth.

The authors of the exhibition aren’t disappearing into the background. They’ve been brought into the foreground in conversation with the materials and talking about their process.

VQ: Your essay was focused on a section drawing of the Mile-High Illinois skyscraper for Chicago [1956]. If you feel that each essay is about the object as much as the interpreter, what do you think your essay reveals about your interpretation of Wright, or your thought process around him?

BB: We showed that drawing in the 2014 show. Wright claimed that all of Broadacre City could fit into this tower. I was very fixated on that. But the top half of that drawing is occupied by this honor roll of architects and engineers—both from the past and Wright’s contemporaries. I thought, What is this group of names? I didn’t really solve it in 2014 and I wanted to go back and understand it.

My working hypothesis—and I think it holds and gives some interpretive power—is that it is a kind of version of Frank Lloyd Wright’s autobiography. He was writing his autobiography throughout his life. It went through numerous editions and got bigger and bigger and bigger, just like that tower got bigger and bigger and bigger.

He’s telling us that this is the genealogy of his own particular genius as a form giver by citing all these engineers. It’s almost as though engineering is just mathematics that hasn’t entered the poetry of architecture, and it takes a Frank Lloyd Wright to culminate that whole history. He’s also trying to write his own place in history. He’s trying to have total control over how he will be interpreted. Even now, more than half a century after his death.

VQ: I’d like to ask you about the ways that Wright ties into some of the thinking that is happening today in architecture. Take his advocacy for decentralization. Obviously, today, architects tend to strive for density, but do you think there are lessons to be gleaned from Wright’s theories?

BB: Well, this is a very controversial topic because many want to see Broadacre as a kind of almost libertarian endorsement of sprawl. That might be an unintended consequence, but I don’t think that’s what Wright is after. There are many things that can be learned now, ironically enough, in terms of the distribution of local services. One of the most fascinating things about Broadacre City is the localization of markets and agriculture and their relationship to one another. It’s almost paradoxical because the very reason, the raison d’etre, for Broadacre is that the car, the telegraph, and the telephone—and later on television—lead naturally to decentralization for Wright. Technology actually produces decentralization from his view.

Yet, today, when I think of the many crises we face, it’s completely irrational, irresponsible to be shipping bottles of water from Fiji to be consumed in New York. We see the farm-to-table movements and locavores, etc. There is a locavore idea at the core of Broadacre, so even if one doesn’t adopt it wholesale, there are many, if you will, retail ideas in Broadacre that again have an actuality. It’s no mistake that it was developed during the period of the Dust Bowl and the Depression. The relationship between thinking about what is “community” and “territory” versus the reality of economics translates to the environmental crisis that we’re in today.

VQ: Do you also see parallels today with Wright and the ways that architects interact with media and the idea of celebrity?

BB: Wright was an incredible presence on television, which becomes the mass medium in many households, really only in the fifties. Wright seizes on that and understands it. If Wright were here today, he’d be everywhere on social media. He would understand the relationship of new technology to fame, to getting your message out, and keeping yourself in the public eye. The fact that he was able to do that when he was in his 80s, in a very persistent and even charming way, is pretty impressive.

VQ: Do you see any architects today who have similarly taken on that mantle?

BB: Well, I think of Bjarke Ingels as a real descendant of Frank Lloyd Wright in that sense. He is an amazing designer, but he’s also a brilliant marketeer.

VQ: Looking back on the essays that you procured for this exhibition, were there any takeaways that were particularly surprising or interesting to you?

BB: The Rosenwald School, I didn’t even know about that. So when I came upon those drawings, and tried to figure them out, I called Mabel and said, “Come look at this, what in the world is going on here? I want to think about this.” Then we discovered there’s a very nice article on it in an obscure location by a specialist named Jack Quinan, so it wasn’t 100% unknown, but still, that to me was a whole new dimension. And the biographical dimension—how did that come to pass? Which leads us to the complex question of how we interpret some of Wright’s views. Do we get a little upset by them because they’re tinged with a certain racism? Do we say, oh that’s par for the course in the period? So, it raises the question that we run into over and over again with our own history.

One of the biggest surprises truly came from the section on Wright and nature in a larger sense, Wright and ecology. Therese O’Malley’s piece looking at light and plant material. Jennifer Gray looking at some of the landscapes that Wright was involved in. Jennifer is really making us pay attention to the fact that Wright is engineering the landscape. It’s not simply this soft touching of the ground. And then Juliet Kinchin has done an extraordinary piece of detective work on this experimental farm from 1929, which predates Broadacre City—it’s actually Broadacre City in gestation.

VQ: Did you parse through the archives, pick out the objects yourself, and then go to an academic that you felt would pair nicely? Or did you go to the academics first, and then ask them to dig through?

BB: We’ve got a super abundance in this country of people who used to study Wright for decades—they are Wright specialists. We want, of course, their wisdom, and we want them to feel at home with the new home of the archives. And there are two of those in the mix, Michael Desmond and Neil Levine. Desmond takes on circular geometry and Neil Levine gives a different view of Wright’s urbanism.

But, all of the others are people who have no Wright credentials. If you’re a member of the Frank Lloyd Wright Scholarship Society, which has an illustrious membership, you will be horrified by this exhibition. Many of the usual suspects are not there. But if having written about Frank Lloyd Wright is what you need to write about Frank Lloyd Wright, that’s like being an architect and not being able to get a commission to build a hospital if you haven’t already built a hospital. How’s that supposed to work?

We really wanted to get fresh people, so we convened a big session and invited people who were doing interesting thinking in architectural history and criticism to ask them, “why would it be interesting today to write and talk about Frank Lloyd Wright? What could an exhibition do?” And we invited them because the themes of their work, seems to us to relate to issues of Wright.

For instance, Spyros Papapetros from Princeton has been working for a number of years on the role of ornament in modern architecture. He hasn’t written about Wright, but ornament is absolutely key to Wright. So, rather than go get the person who has written three books on Wright and ornament, we have somebody who’s never written about Wright and ornament, but thinks about ornament all the time.

Likewise, Mabel Wilson has not written about Wright, but she has written a wonderful book called Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums [University of California Press, 2012] on the spaces of display of the African-American. So we wanted to bring together a group of people who ask interesting questions and ask if there’s something in the Wright archives that sparked their curiosity and might be the point of entry towards some new thinking. It did not have to be 100% conclusive—not all archival research is 100% conclusive—but it can raise new questions. That’s how we went about it.

VQ: It is a fairly unusual tactic to ask people to step outside their specialties and comment. Was it something that you felt confident about, or were you anxious in the beginning?

BB: I was anxious about it, but a curator who doesn’t take risks is not a very interesting curator. For Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront [MoMA’s 2010 exhibition about rising sea levels], I invited five interdisciplinary teams of people to redesign New York for climate change. We told told the architects when they were done we were going to exhibit their work. Telling people you’re going to exhibit their work before they make it, that is really risky. So I’m used to this!

VQ: And are you happy with the results of the new show?

BB: Well, it’s a little early to congratulate one’s self because the show hasn’t opened and we haven’t seen reaction of the public. The risk is still there of what the non-specialist audience will make of a collection of facets of Frank Lloyd Wright that don’t even try to coalesce into a new monograph, a new synthetic view, a new Frank Lloyd Wright. Not every aspect of his career is dealt with. You would expect in any show on Frank Lloyd Wright that the domestic environment would be a principle theme, but here it’s not.

My hope is that people will discover that Frank Lloyd Wright is even more intriguing than they already knew. And that having gone through the monumental effort was worth doing. I like to think this exhibition is the announcement of a new period of broader engagement with Wright. For scholars, but also for the general public. I hope people will see this as exciting because Wright turns out be more interesting, more intriguing, more diverse, more contradictory than they already knew. And that they will also go away with some understanding and, I hope, appreciation for how scholars work in an archive, what it means to investigate a historical situation, that they might understand that history is about interpretation and not about finding truth. The hard concept of that is at the core of this.

If you enjoyed this article, then you may enjoy “The Protegé’s Turn: Unearthing the Work of a Frank Lloyd Wright Student Who Helped Design Usonia.”