August 8, 2019

Building Sisterhood: How Feminists Sought to Make Architecture a Truly Collective Endeavor

Metropolis looks back at the history of feminism and architecture, finding areas where there has been progress—and where advocates have lost ground.

Women are indispensable members of the design community, yet their contributions are still often taken for granted. This week on Metropolismag.com, we highlight women who are doing innovative and probing work in the fields of architecture, design, and urban planning.

Lady architects, I see you.

Female architects, I see you.

Female-identifying architects, I see you.

Nonbinary architects, I see you.

I see you in your hard hats or Nike kicks designing, curating, teaching, and writing. I see you helming firms and leading architecture schools.

I see you opening Rhino, crunching spreadsheets, and juggling work-life balance.

And I see you, like me, cringing with frustration when another well-meaning article asks: Where are the women architects?

I’ve had Lizzo’s fierce new album on heavy rotation lately. It’s an anthemic celebration of self-love and acceptance. So you’ll have to excuse me when I say: Bitch, please. We’re here. If we can’t see ourselves, who will see us?

Since the early days of the women’s movement, women in architecture have been tasked with answering the question of the numbers in their ranks. Though the percentage of female practitioners has increased over the years, moving from single digits to low doubles, the question persists. It’s no wonder that “Where are the women architects?” (WATWA), an inquiry powerful men defend as neutral, would be so triggering. Visibility, often manifested as tokenism, overshadows intellectual and creative work.

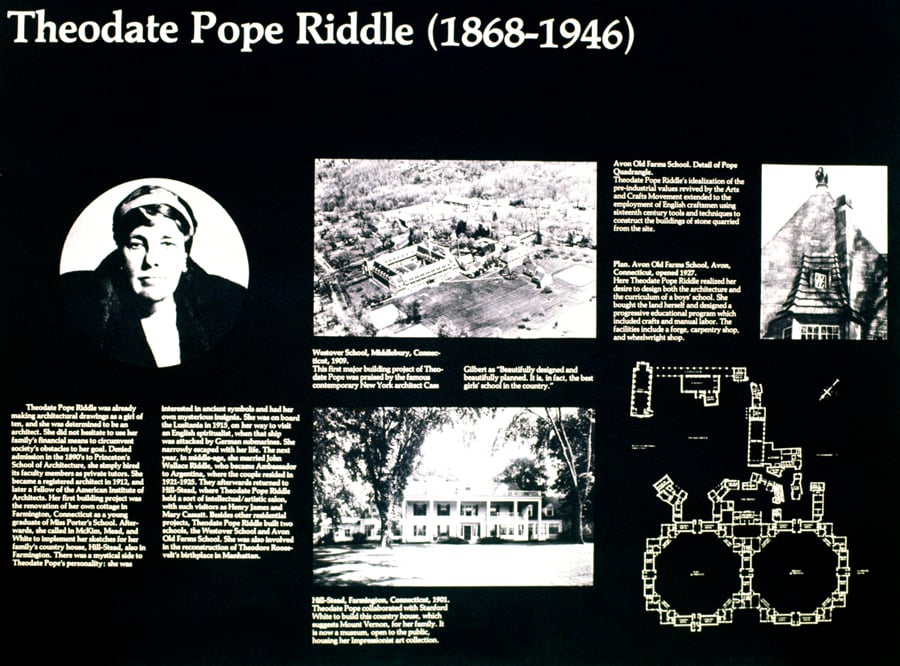

Despina Stratigakos, University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning professor and author of the 2016 book Where Are the Women Architects?, posed the question as a provocation, not as a kind of binders-full-of-women show-and-tell or call for statistics. “It’s erasure, not an absence,” she says. “I was realizing the richness of the history and the people, but I couldn’t see that world reflected in books and museums.”

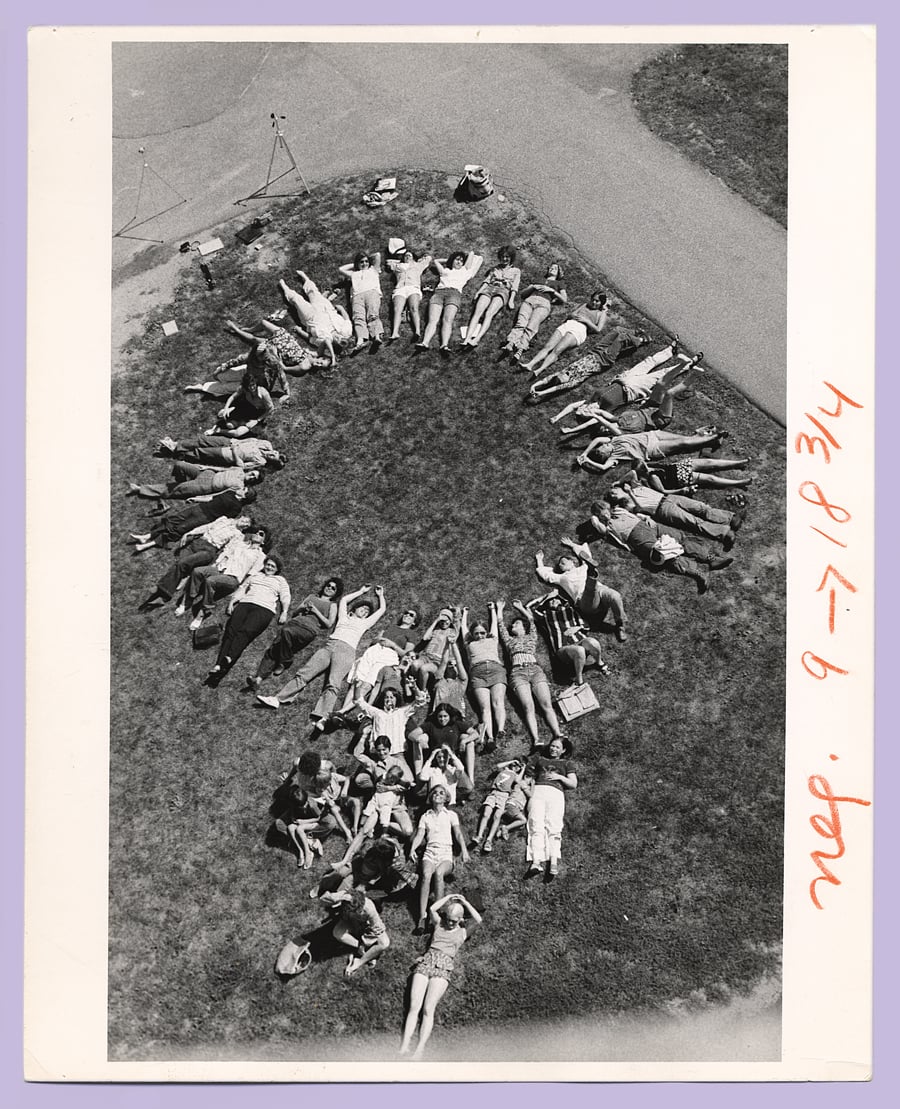

For Stratigakos and many of today’s feminist practitioners and historians, the landmark 1970s exhibition and publication Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective marks the first attempt to reclaim a history of women in architecture and to do so on its own terms. Organized by The Architectural League of New York and its then newly founded Archive of Women in Architecture, the exhibition opened at the Brooklyn Museum in 1977. The gallery was filled with rows of drafting tables, each of the 99 of them topped by an exhibition board chronicling the contribution of women in the profession historically and in contemporary practice.

In the opening pages of the Women in American Architecture catalog, editor Susana Torre rhetorically poses what she describes as a “persistent and reproachful question”: Why have there been no great women architects? Her answer follows the argument of art historian Linda Nochlin, who called the question bait. Torre demands that we dig up “examples of modest, albeit interesting, buildings and valid, if insufficiently appreciated, careers.”

To answer faithfully, as we well-trained women and feminists are prone to do, is to fall into a trap that aligns exceptionalism with visibility: Women must be great to be seen. Today we might call it the Zaha trap, the Jeanne trap, the Liz Diller trap, so familiar we’ve become with a handful of talented architects that their full professional monikers are chummily abbreviated. Torre’s text, in outlining the major prompts raised by the exhibition, suggests an alternative to the singular design star: “[W]hat are the interrelation-ships of woman as consumer, producer, critic, and creator of space?”

Revisiting Women in American Architecture, this rejection of the star system stands out as prescient. Consciousness-raising included recognizing the work of particular designers and articulating historical structural conditions that have kept people from advancement because of gender, race, or sexual orientation. These include lack of technical education, limited access to architecture schools, and conscription into the “women’s work” of designing kitchens and other domesticities.

In a recent interview via email, Torre stressed the importance of celebrating the choral nature of design over the sole-genius model, in which the extolled freedoms of a creative life are acknowledged as a type of gender and class privilege.

“How many women partners in the most important offices are married or devote significant time to developing and enjoying a ‘personal’ life?” says Torre. “Until that changes, until women are more nearly as free as men to devote their energies to their profession, the difficulties of reconciling the demands of personal and professional life will continue to be a major obstacle for women.”

While it’s obvious that many people author buildings—teams of designers, consultants, contractors, fabricators, or builders—the singular model persists. Repositioning architecture as a collective and interdisciplinary endeavor is at the heart of feminist practice. Today’s plural feminisms encompass gender equity and sexual identity and embrace issues of race, social justice, and care—especially the care of the planet.

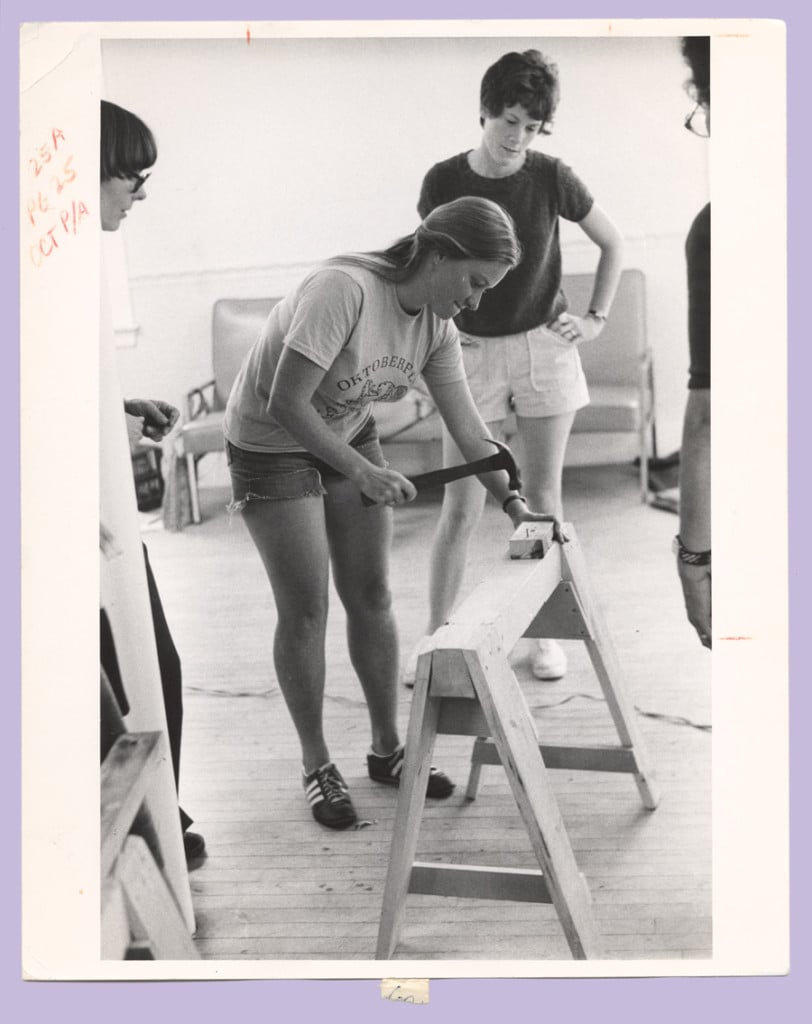

“We are asking the wrong question,” says architect and Syracuse University School of Architecture professor Lori Brown of WATWA. “It’s not just about writing women into bibliographies and not just about adding them to design teams. We need to ask, what are the different ways that women create practice? We’ve been kept out by this patriarchy, so we are inventing different ways of practicing. Feminist models challenge the status quo—challenge the ways things get built.”

She points to the work of earlier feminists, beginning in the 1970s, and the ways those practitioners invested in communities and in making spaces like women’s shelters, day care centers, or community gardens, which supported the everyday needs of women. She sees this legacy in her students’ interest in architecture’s social impact.

Brown edited the 2011 volume Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture and is one of the cocurators of the traveling exhibition Now What?! Advocacy, Activism & Alliances in American Architecture since 1968, organized by the nonprofit ArchiteXX. Both share an interest in highlighting alternative design methodologies and how those ways of working could provoke change. For example, an essay in Feminist Practices by critic and historian Jane Rendell suggests collectivity, interiority, and alterity as approaches to design that expand the conversation beyond simply what we make or where we happen to work.

Importantly, the book and the exhibition act as critical benchmarks where a group of alternative ideas and voices come together. Indeed, Now What?! is structured as a timeline that invites viewers to see both the parts and the whole: the individual actions and organizations representing the goals of the civil rights, women’s, and LGBTQ movements—such as the Organization of Women Architects and Design Professionals and The Women’s School of Planning and Architecture—as well as the recurring waves of activism within architecture that seem to emerge every generation, only to eventually recede from the discourse.

“Visibility is a critical component, but we need a more diverse design community, a more diverse client community,” says Brown. “Clearly, the capitalist system is at the root of so many problems socially, racially, so until that system changes, we have to figure out how to push our own agenda.”

Seeds of such an agenda can be found in the pages of the magazine Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. The 11th issue, titled “Making Room: Women and Architecture” and published in 1981, was edited collectively and filled with a broad range of stories devoted to questions of women and architecture. Heresies ran from 1977 to 1993, and throughout its history, different teams of editors would gather to put together individual issues, a routine that would limit structural hierarchies and frustrate the assumed power of expertise. The seven-person team for “Making Room” included architects and designers, educators and activists: Barbara Marks, Jane C. McGroarty, Deborah Nevins, Gail Price, Cynthia Rock, Susana Torre, and Leslie Kanes Weisman.

The content varies widely, from polemics and histories by notable contributors like Torre and historian Gwendolyn Wright to case studies, such as an early project by Sharon E. Sutton, who would later write the book When Ivory Towers Were Black: A Story about Race in America’s Cities and Universities, a tale of the fight to change the status quo at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.

Weisman’s contribution as architect, editor, and essayist takes to task the cultural stereotypes that continue to hold back the field—the skyscraper-versus-home binaries that serve as a kind of perverted gender shorthand. By introducing the term “environment” she argues for a civic realm—public spaces, transportation, housing—that “supports the realities of our lives, not the cultural fantasies about them.” Several other entries tackle race, poverty, and gender inequity by looking at conditions of public housing and alternative responses, such as the founding in 1979 of the Women’s Development Corporation, a non-profit housing developer still operating in Rhode Island.

On the other end of the spectrum, “Herspace,” by Noel Phyllis Birkby, architect and cofounder of the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture, presents some findings of the Women’s Fantasy Environments workshops, which she and Weisman conducted. The case studies reveal an interest in pursuing forms—hearths, gathering spaces, domes—that are freed from the cultural inheritance of male-dominated architecture. While the question of what constitutes a female design aesthetic has largely fallen out of favor, Birkby’s insistence that it has meaning cuts through the decades.

“The plurality and the conflicts were right in there,” says Stratigakos, reflecting on the continued importance of Heresies. “It was very brave. It was very fertile.”

Third-wave feminism generally blasts the second wave for catering to the needs of white, middle-class women, but in looking back at “Making Room,” what stands out is the publication’s emphasis on social justice, which anticipates contemporary feminist ideas of intersectionality and a diverse mix of contributors.

“That’s one of the things that the third-wave movement got wrong,” says Joan Braderman, a filmmaker and long-time member of the Heresies Collective who made a documentary on the magazine. “We have gotten a bad rap from the daughters because we were mothers. We made a commitment in the first meetings to get as many points of view as we could—every community in America, La Raza and the Panthers’ women’s caucus.”

When reading “Making Room” today, the semantic difference between “women and architecture” (the subtitle of the issue) and “women in architecture” (contemporary parlance) is of critical importance. The former refers to relationships between women and the built environment, whereas the latter is more myopic, narrowing the scope to the purview of the profession. Over the past four decades we’ve unwittingly yielded territory. Representation and visibility matter, but so do our feminist histories and practices. Let’s stop asking where the women architects are, but instead reclaim that “and.”

You may also enjoy “Meet the Designers Behind The Wing, the Coworking Company Creating Spaces For and By Women.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]