January 18, 2024

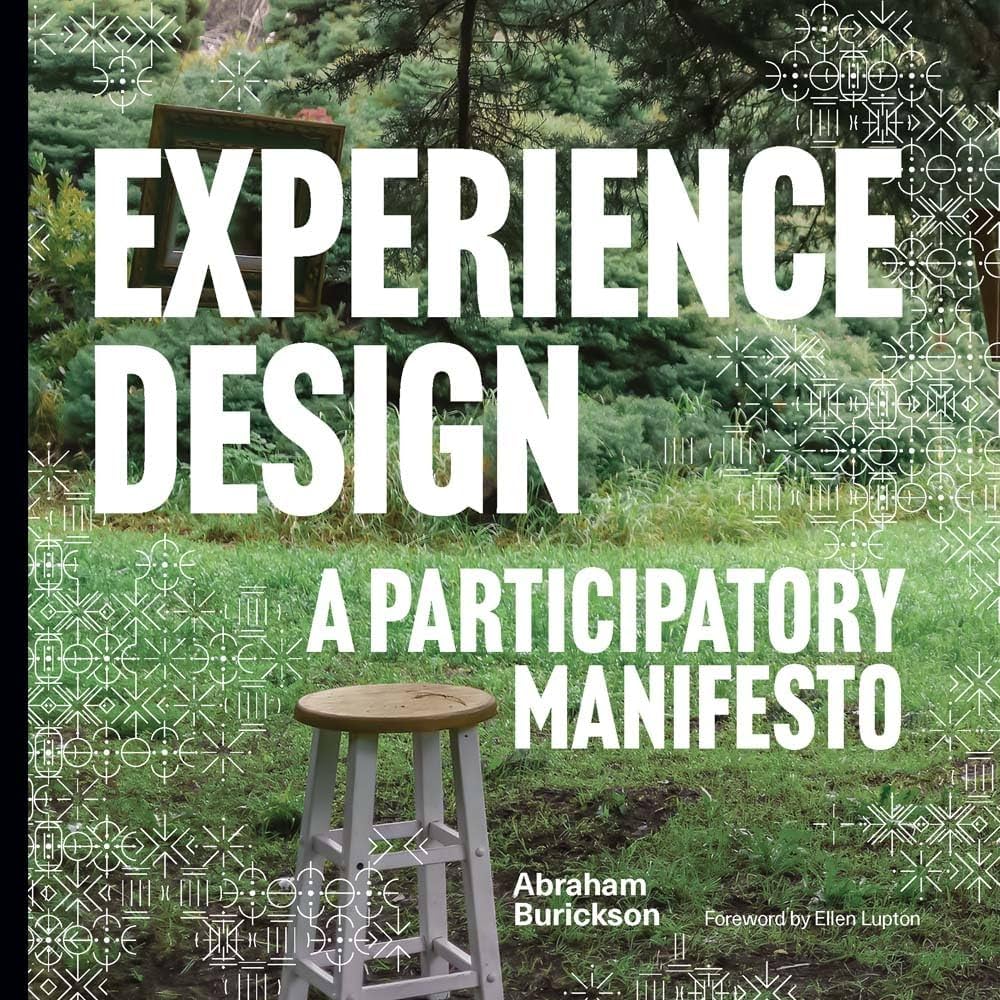

How Abraham Burickson Designs Experiences, not Things

Sam Lubell: Can you say in a couple sentences what experience design is?

Abraham Burickson: Experience design quite simply is making the experience, the product of your work rather than the thing that facilitates that experience. That’s it. And once you do that, once you look at the experience as the goal, the thing becomes just the material, the cup holder, the building, the pair of shoes, the org chart. It becomes material for the creation of that experience. Everything falls from that.

SL: Tell me about your background, and how it took you to working on experience design.

AB: When I was a kid, I would walk down the street in New York, and I would see those buildings and think, not, what a great building that is, but what would it be like to be in there? When I got old enough to be able to travel and experience different things, I was always drawn to architecture, particularly when I would encounter a building that that affected me, that changed me in some way.

When I was an undergrad, I took a gap year and ended up in the Middle East. I was walking the streets of Istanbul and I remember walking into one of these mosques. You don’t just walk in, you take off your shoes, you wash your hands, you go in via a prescribed ritual. This is a performance for yourself, to help you orient yourself toward the world that the building is trying to generate for you. And the effectiveness of this was so powerful. I would walk into these buildings and feel myself reoriented. You’re carried by the space, by the ideas, by the narrative and the ritual. You’re changed.

When I got home, I started to see that everywhere I went—buildings redefining who I was. Since there wasn’t really any experience design program, it was obvious I had to transfer to architecture school. I was a little bit of a fish out of water. I wasn’t concerned with the materiality, so much as the experiential reality of architecture. School was very, very, very thing focused. And when I started working for firms it was the same way.

I was out in San Francisco. And I had a friend who was a was a playwright and a painter. And I was an architect and a poet. And we were having this conversation, about creating experiences rather than things. We got a bunch of artists together and created these experiences for one person. We would study them for quite a while. They’d fill out questionnaires. We’d talk to all their friends and family. It was an experiment (later called Odyssey Works), but it just kept going. It’s still going and it’s 20 plus years later.

It became essentially a laboratory for the design of experiences. We had all this information. We had ourselves being forced to think differently, to say not, “how can I sell more tickets or close this deal?,” but, “how can I affect this person in this particular way?” And furthermore, “how should I be changed in order to do that?” This experiment went on for a long time and we brought in artists and designers from all different disciplines. And we started to see that essentially this is a way of thinking that is discipline agnostic.

Meanwhile I was finding my own architecture practice to be more and more frustrating. I found we were getting into our projects so late; we would start already with the brief, which is how it goes. This is your brief. You have X number of bedrooms, X amount of square footage, X space. But the experience we’re interested in is so much broader than this. We’re interested in intervening in a life. We’re interested in how this moment, which is just an unbelievable outlay of resources, either for this institution or this organization or this individual or this family. And it’s not just financial resources—it’s material resources, sociocultural resources. How much time is dedicated to actually considering the long-term impact and how does it align with the value systems?

So, I started creating in my own architecture practice the Long Architecture Project, by just doing what we call phase zero, which is where we start with that question. Starting for an audience of one, where we’d have them fill out questionnaires, spend a lot of time going for walks, discussing the future that the client wishes to create. Talking not just with the clients, but with other people who are going to be affected by this work.

That is the parallel project to what I’m doing at Odyssey Works. Odyssey Works has the performances, which is a kind of laboratory for this, and we have our certificate program, which is a school for this. And then I put out this book, the vision being: can we offer this tool set to makers in any discipline and say, if you think this way, you think about experience before the thing, if you liberate yourself from these kind of traditional limits within which the thing lives, could you align your work more specifically with your values, with your aim in life, with what you would achieve? Could we be thinking about legacy from zero instead of after it’s all done?

Let’s talk a little bit about how you’ve organized the book. You start with phase zero, the idea of not just what are you hoping to build, but what kind of life do you want to build? And then it moves on to strategies like empathy, framing experiencing, engaging the whole person. So how did you develop these different techniques? Where did these come out of and how do they work together?

They came from both the years of experimentation and a lot of the consulting and experience design work we’ve done with people in various fields. There are a few main intentions in the book, and they were focused on a few different tools for bringing experience design into whatever practice you have. For example, there’s this idea of frames, which says that inside the picture frame, there’s a picture. Outside the frame, it’s not aesthetically important. And then we talk about once you’re inside a frame, the frame may be a building, the frame may be a picture, the frame may be a movie screen. Frames can even be determined by rhythm or motion if they’re really carefully crafted. And then we have this related idea, which is world building. We love looking at movies, fantastic worlds. And if we sit back and ask why, it becomes clear that it’s because we engage in this imaginative act of being different, of occupying that space with that attitude of having this particular sense of adventure that is emergent from that world that looks that way. And that’s key because worlds are sort of giant frames that you can’t see the outside of. Worlds determine what is possible and what we can be. How we look at things, how we understand ourselves. This is taking this little idea of frames and getting really big and saying, in world building, the structuring of attention is perhaps the key to making enormous changes. I talk about Gandhi in the book and how he was really a world builder. He was thinking about not how can we overthrow the British with our guns? Because how could he? But how could we overthrow the British by changing the world that they had installed. By changing the population, by changing the physics, by changing the social rules, by altering the way people understood themselves and eventually, essentially toppling this empire. But the power of world building, down from a role playing game to a home, all the way to decolonization is enormous, continuous. And it’s really an exercise and understanding how attention is structured.

There’s another zone of the book, which is about how you actually structure time to create events and a sense of things really being live, of things mattering. And one of the main things about this is the unknown. Traditional design hates the unknown, it is a problem we’re trying to solve for. The unknown creates a problem, and we devise a solution. That’s design, right? But experience design says the unknown is life, and not a problem. And rather than try to get rid of it, what if we could embrace it, engage with it, understand that it is what keeps things alive and involve it in a dialogue with our design? And then the question is how do we structure things with that in mind to potentiate transformation, to create memorable moments, to have the effect we’re interested in. And then there are some tools, both for research and for documentation and notation that are pretty essential, because you can sit down and think about the experiential aim that you have till you’re blue in the face. But if you can’t communicate that to anybody and you can’t write it down, you’re not going to get anywhere.

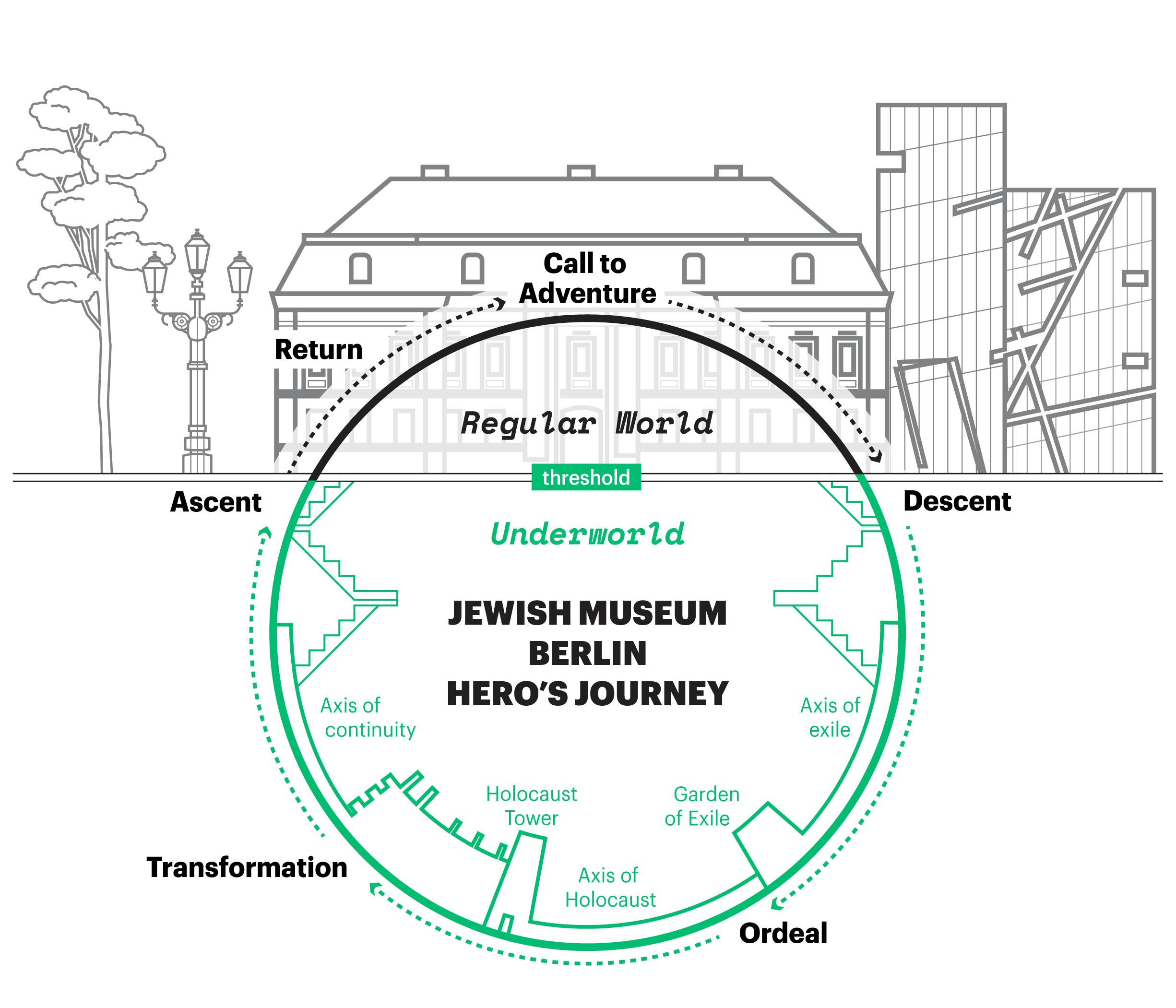

The diagrams in the book are very useful for that. It seems like something you specialize in. Is that something you’ve done for a long time? How has that happened?

It emerged, I would say naturally, in our process of creating Odyssey Works. There was somebody who was quite good at diagrams who brought it to the table, named Travis Weller, who is a music composer. One of the things they do is mess around with scores until they’re unrecognizable. He brought that mindset to our practice, and I was hooked immediately. Because it was so clear. We were so frustrated trying to document our work. We had scenes, but they were all sort of improvised, but around structure. We had aims and when things got bigger, and it wasn’t just me and the other director coming up with everything, it was very hard to continually communicate how that aim fit into this scene without just saying, “Just do it.” Right? And once this was brought to the table, I was hooked, and I just kept going. And then eventually I found that it became my favorite mode of composition. Diagramming is a mode of thinking that allows you to think about the things you want to think about. I would produce 20, 30 diagrams, until I figured out what I was trying to get at. And then use those diagrams to start the conversation with my team. They are proposals, they are questions, they are possibilities.

What is the importance of some of these themes to you personally? There are so many of them— immersion, humility, emotion. And I guess they all fit together into what you’re talking about, it’s having things be transformative.

I think the first question we have to ask about transformation is why are we trying to transform ourselves or anybody else? And if you can say why, then you can find that all these other elements pour off of that. For instance, a client comes to me with a brief. They want a sustainable house. Is my phase zero, my aim, to design a sustainable house? Maybe a LEED certified whatever? Or is there something more to that? And we dig into it. And they say, ‘Well, I recognize that the world is in crisis, and I see myself not as part of the solution, and I wish I were.’ And suddenly the question becomes totally different. The question becomes not can this house be less of a problem? But how can I, the client, and my family, have an entirely different relationship to the environment? The design of that is so different from the design of a net-zero house. Of something with solar panels, or of maybe a straw bale house. Maybe that’s there. But then we start asking the bigger question, what is the scope of this? How long would it take? And what do you look like on the other side? How are you transforming? Is your family on board? Is your neighborhood or your community? And how are they transforming? What are they bringing to the table? Because transformation is something that we are participants in. You have to be willing; you have to be on board. Then it’s transformative. It’s a participatory activity. We’re not thinking about design as fetish objects or entertainment. How do we structure the world that we are creating here? Because everything we do is in some way, an intervention in a world.

And these questions then have answers in the tools of world building and the tools of interactive narrative and the tools of framing. And so, when you put it all together, it becomes a tool set that’s in your pocket, once you understand the goal. Instead of saying “There’s something wrong. We’re going to find out what’s wrong, and we’re going to fix it.” Rather we’re saying, “What is the world we want to create? And what is the life we want to create?”

Every practice engages these aims, engages these tools. It always comes back to that. The goal is not the thing. The goal is not the article, the goal is not the house, the goal is not the org chart, the goal is not the butts in seats at the show. The goal is this experiential aim, and everything hangs off of that.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

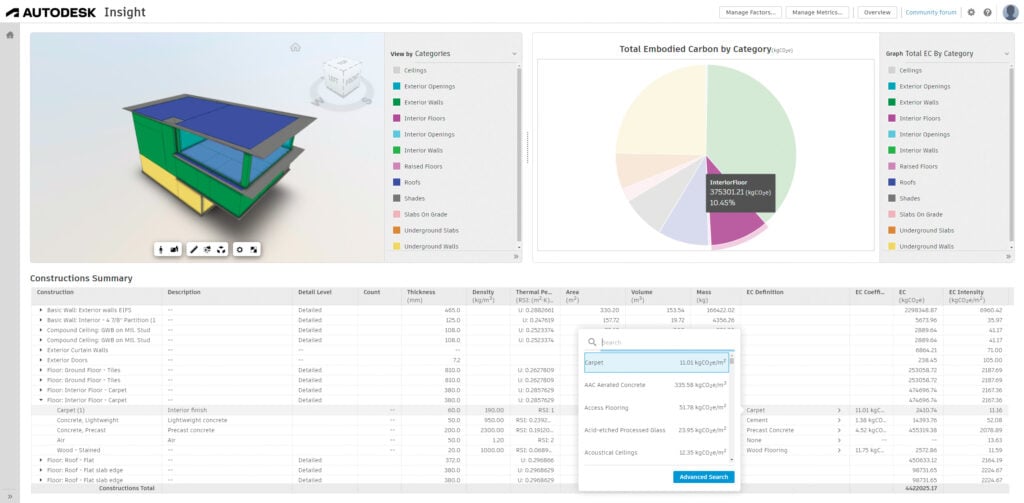

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.