July 30, 2020

How Atelier Office Is Upending the Architectural Paradigm

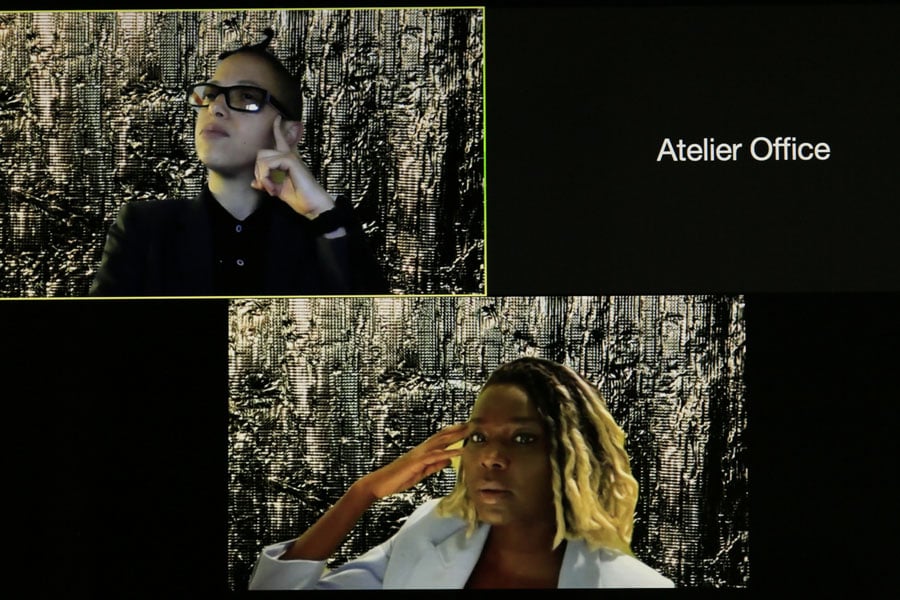

Amina Blacksher and V. Mitch McEwen’s new venture points to a fresh model of design practice.

Putting together two last names is an old-school way of naming a firm, says the architect V. Mitch McEwen. So this summer when McEwen, the cofounder of A(n) Office, merged her studio with that of Atelier Amina’s Amina Blacksher, the duo wanted a name that blended their practices and also described their unique approach. Thus: Atelier Office, a name that draws from the nomenclature of both studios and combines, as McEwen explains, “the design work (atelier) and the project management (office).” Aligning two different types of workplaces, they “both depend on a mix of skills and tactics and attitudes that [Blacksher and McEwen] mediate digitally.”

Together, the two are interested in how architecture as a practice and as a business can be done differently. Aside from deep backgrounds in design—the duo has worked separately at the New York City Department of City Planning and firms including Bernard Tschumi Architects and BIG, in addition to running their own studios—McEwen and Blacksher each bring uncommon expertise to the table. McEwen has a background in finance, while Blacksher has worked in the past with dance, fashion modeling, and government. For Atelier Office, hardcore architectural experience meets extra-architectural skills, an interest in noninstitutionalized knowledges (such as the on-the-ground engineering Blacksher has been researching in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro), an embrace of rhythm and embodiment, a fascination with media culture, and a commitment to technological experimentation. “There is something very Black about having these diverse skill sets,” McEwen notes. “It’s slightly beyond survival, it’s somewhere between #BlackExcellence and survival.”

One significant area of innovation is in the use of emerging technologies. “We’re both interested in computation and in things like robotics, but I think Amina is more of a design technique geek than I am,” McEwen explains. “I like design techniques but I secretly like them for what they do for politics and what they do conceptually.” This balance is critical to the work Atelier Office will be undertaking, with ventures such as a media startup in East Africa, a music studio in upstate New York, an arts non-profit in New Orleans, and an invitational public art project in a design district. “I’m such a formalist I wouldn’t have even thought about doing a spreadsheet,” Blacksher jokes, “but that’s part of what’s brought us together. I might have a pie-in-the-sky idea, but Mitch is the ‘closer.’ She says, ‘no, we can do pie in the sky.’”

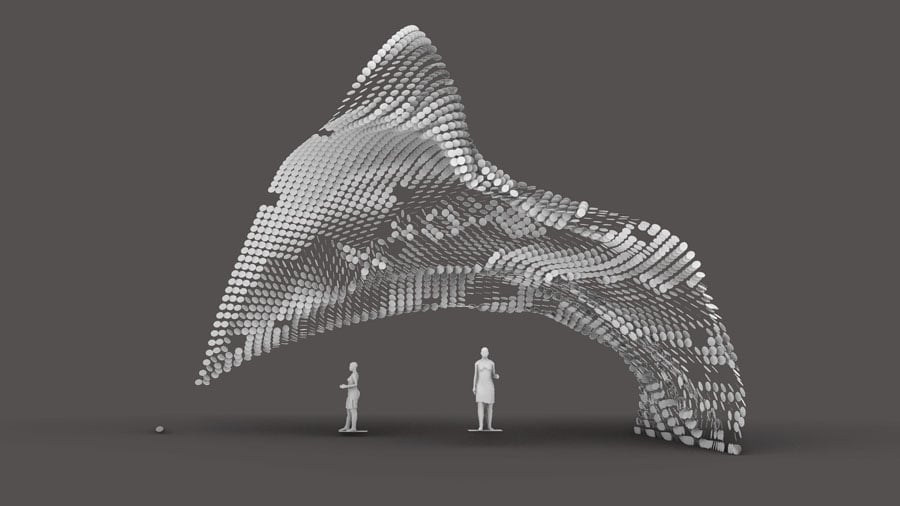

Their technological interests range from software solutions like Revit to what McEwen refers to as more “esoteric plugins” and processes like 3D printing, vacuum forming, and CNC cutting. “We tend to mix high tech and low tech,” McEwen explains, pointing to examples like “combining a hand-held tool with a robotic arm” or blurring the boundaries between analog drawing and algorithmic design.

One recent experiment sees architectural-scale sheet metal borrowing from the aesthetics and behaviors of formalwear textiles. And fashion has influenced the studio in other ways, such as in the presentation of client portfolios as “look books.” “We’re bridging the gap or breaking down the division between ivory tower academic theory and popular culture. We’re mashing up the two, just like couture borrows from the street all the time,” Blacksher says.

Atelier Office’s first projects all situate themselves within art and culture. McEwen explains that she feels clients are seeking out the studio for their “[attunement] to media and culture, and a relationship to contemporary culture and technology.” Clients, she explains, “are defining themselves by how they want to relate to the public.” This, and a process based on mutual dialogue, will guide the creation of forms and use of materials more than a signature style. It’s not about image; it’s about politics.

Atelier Office develops projects holistically, working with clients on aspects that might not conventionally be seen as architectural. “We’re talking about the scope of what a company can build internationally with an investment round, or we’re finding land to buy, or we’re setting up an institute and founding board as a prelude to building,” McEwen explains of the ground-level, integrated work Atelier Office is doing. “We’re not starting with formal massing or with materials,” Blacksher adds. “We’re beginning with history, with research into a place. The project starts a lot earlier than even the first drawing.”

Just as Blacksher and McEwen intend for Atelier Office to flip how architecture is done at a practical level, they’re also questioning larger structures, and asking how our present moment might be a turning point for the field and for culture more broadly. “We see this as an opportune time to put our position forward on how spaces are inhabited, a time for questioning and inverting hierarchies,” says Blacksher. “These questions are in the fibers and foundation of our practice. There are no assumptions.”

You may also enjoy “Can a City Be Feminist?”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.

Recent Profiles

Profiles

Chris Adamick Designs for Life