December 19, 2022

CO Adaptive Uses Low-carbon Design to Rejuvenate Old Buildings

Today, terms like “sustainability” and “carbon neutral” get tossed around prodigiously. It almost seems that the slightest public acknowledgment of climate change and environmental pollution is enough for architecture and engineering firms to stamp their ground-up projects as “green” (a public relations projection otherwise known as greenwashing). However, there is no escaping the reality that the greenest building is the one that is already built, and adaptive reuse is the surest means of sequestering embodied carbon while limiting the carbon-intensive manufacturing associated with the building trades. CO Adaptive Architecture, a Brooklyn-based firm founded in 2011 by Ruth Mandl and Bobby Johnston—the couple met while studying at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation—places these concerns front and center with a growing body of work that playfully reimagines historic structures while incorporating low-energy Passive House design.

The ten-person firm (seven work on the architecture side of the practice, while three focus on construction with CO Adaptive Building LLC) recently relocated to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a sprawling former military base–turned–commercial and industrial mecca, where they set up their office in a loft space overlooking Brooklyn and Manhattan—a fitting backdrop for a design ethos that seeks to emphasize the city’s existing fabric while repurposing its cast-off pieces. For Mandl, this approach dates to her time studying interior design at London’s Kingston University. “In the final semester we were tasked with picking an old building in London, researching its records and history, and then developing an adaptive reuse program. Big cities, such as London and New York, are filled with such opportunities,” says Mandl. “We need to bring our old building stock into the future, and we need to make it more efficient without losing all that history or wasting all of that embodied carbon.”

What does this methodology look like on the ground? “When we take on projects, we’re looking at what the minimal intervention could be,” says Johnston. “Does the layout need to change? Can we keep things the way they are, and can we keep existing materials intact?” For one, CO Adaptive Building steers clear of demolition in all its projects, aiming to fit each within the larger circular material economy model. To do this, the firm partners with Big Reuse, a local nonprofit salvager, to match each project with an appraiser who can specify particular items for resale, such as wood casings, radiators, and plumbing fixtures. CO Adaptive Building then provides the owner an appraisal report, which lays out the potential tax rebate afforded to the homeowner in donating items. Non-appraised items are then carted off to Cooper Recycling in East Williamsburg.

Before CO Adaptive Building was founded in 2022, the firm put some of these ideas into practice at the Bed-Stuy Passive House (2017), the home of Mandl, Johnston, and their daughter Lucia. The three-story property was originally built in 1889 and had retained its Victorian-era interior bedecked with ornate wood- and plasterwork. The project saw the careful deconstruction of all woodwork and casework elements, which were later refinished and reinstalled—which provided the firm enough wiggle room to reinforce existing structural joints. They also wrapped the building in an airtight vapor barrier membrane and insulation and installed triple-glazed windows, all details critical to bringing the house up to Passive House standards. In line with CO Adaptive’s commitment to energy-efficient design, the existing natural gas lines were removed and replaced with an all-electric system powered by a newly installed rooftop solar array.

A similar project currently underway is the Tiny Queens Passive House, which, as the name suggests, is a Passive House renovation underway in Queens. The home, built in 1945, is undergoing deconstruction, in which many materials, such as wood and bathroom tiling, will be upcycled for new uses (including lighting fixtures that will be installed in CO Adaptive’s new studio space) and the existing perimeter will be stripped to allow for sealing. Exterior changes come in the form of a checkerboard infill brick pattern that provides contrast with the existing brickwork, showcasing where exterior changes were made. Durable low-carbon materials such as linoleum, upcycled terrazzo, reclaimed wood, and porcelain tile will be used as flooring within the interior spaces. A solar canopy, installed by Brooklyn SolarWorks, will power the home and make it net positive, producing more energy than it consumes and creating passive income for the client.

The recently completed Timber Adaptive Reuse Theater, a nearly 13,000-square-foot start-up space for theater companies called the Mercury Store, scales up the methods CO Adaptive has developed in its residential projects. The former metal foundry site in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood was subdivided into a series of office and fabrication spaces, which effectively concealed the building’s skylights and double A-frame roof trusses. CO Adaptive removed this clutter to create lofty spaces for rehearsals, and to install full-height folding doors that add flexibility to the facility, supporting a larger range of programming. The existing timber structural system and masonry walls were retained and refurbished, while lumber removed from the space was carefully deconstructed and salvaged for newly inserted details such as guardrail posts for glass balustrades.

To support additional space for the building program, the firm installed a cross-laminated timber floor plate supported by a glulam post-and-beam system; it is the first commercial adaptive reuse project in New York to use cross-laminated timber to this effect. All of those changes were afforded through insulating the building from the exterior, behind a new aluminum facade, which reduced the need for air barriers or insulation within interior spaces.

CO Adaptive’s own workspace is also a site for experimentation. Moving from Bushwick to the Brooklyn Navy Yard has afforded the studio sufficient space to develop a design-build branch. Its first objective with the space is to develop a modular wall panel system, possibly composed of reclaimed lumber and wood-fiber board, which aims to provide a modular solution to insulate and air-seal existing buildings. “If you have a historic landmark building, prefabricated insulation panels on the exterior are not going to be the best approach, or even feasible,” explains Johnston. They hope to have a more actionable prototype in place by the end of the year, Johnston concludes: “With the smaller blocks and components produced by our design-build studio, we hope to establish a scalable way to implement high-efficiency insulation from the interior. We don’t just want to cater to higher-income families, and the prefabricated insulation panels could serve to make Passive House design more accessible.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

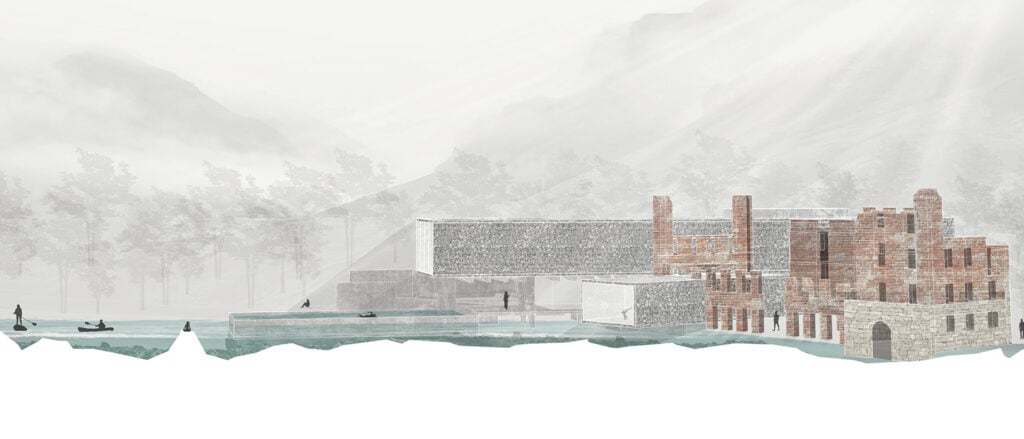

These Architecture Students Explore the Healing Power of Water

Design projects centered on water promote wellness, celebrate infrastructure, and reconnect communities with their environment.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.

Profiles

Future100: Lené Fourie Creates Adaptable Interiors

The University of Houston undergraduate student is inspired by modular design that empowers users to shape their own environments.