July 3, 2024

Colombia’s Fundación Organizmo Builds for Planetary Well-being

Modeling Regenerative Design

And that is exactly what Organizmo’s founder Ana Maria Gutiérrez is doing on her expansive property in Tenjo. Pioneering educators in low-impact construction techniques, alternative technologies, and ecological restoration in Colombia, Organizmo has worked with different communities across Latin America to develop sustainable habitats and new modes of artistic and cultural expression. And after hearing Gutiérrez speak at re:arc’s Arquitecturas del Buen-vivir Planetario (architectures of planetary well-being) symposium a day prior, we were all more than eager to get out of the city and into the architect’s compound of community-built earthen architectures.

When we get out of the van, we are greeted by a big white farm dog with a long, dreadlocked tail whom Edgar refers to as “rasta dog” for the duration of the tour. And then we spot Gutiérrez, who immediately extends a warm welcome, letting us into her home to use the bathroom, and giving us instructions on how to use the open-air composting toilet (a first for many of us.)

Originally from Colombia, Gutiérrez moved to New York City in 2001 to study architecture at Parsons School of Design. She returned in 2008 when she inherited around 30-acres of farmland from her father. “I was obsessed with earthen construction—adobe, wattle and daub, rammed earth—all possible earth techniques,” she explains. “And that’s how we arrived here. We started building a model of community construction modalities, but we had no expertise in anything, just the love of the earth.”

Essentially, Organizmo is a community-based bio-construction school that provides training and research into regenerative building systems and local craft practices. Gutiérrez explains, “We understand that everything we do is a living school, and the teachers are the communities we work with.” She has worked in the Amazon, the Pacific coast, and now Organizmo is working at the border of Venezuela.

“Every time we go somewhere new, we question a lot—our perception of architecture, of sustainable settlements—and we come back here and integrate what we’ve learned.”

Preserving Traditional Knowledge

Craft is an essential part of the cultural expression of Colombian territories and in the High Andean region, artisan trades hold significant importance. Created with the help of the Ministry of Culture, Organizmo’s school of crafts aims to connect communities to the Traditional Andean Trades by offering workshop-based training programs in wood, forging, ceramics, weaving, agroecology, and local cuisine. The training programs are a way for local artisans to learn about regenerative ecosystems while also promoting their cultural identity and transferring traditional knowledge to new generations.

For Gutiérrez, craft is the foundation of great architecture. “Everything you see here has been built through workshops of people who have never built before,” she explains. Within the organization’s Sustainable Settlements Department, she has hosted workshops on bio-construction techniques from bamboo, straw bale walls, and natural fiber roofs to composting toilets, alternative energies, and biodynamic agriculture, among others. “Every time [we host a workshop] we realize that there is something else we’re missing in our understanding of architecture.”

Weaving a Women’s Space

Gutiérrez leads us through patches of tall grass, banana trees, underneath a bamboo pavilion, and past painted mushroom murals and decorative clay reliefs. We eventually come to a structure that appears to be 90 percent palm roof.

“I saw this house and was like, ‘Wow, how do you weave that roof? I want to see and learn and teach it.’” Guided by Mamo Senchina Cogui of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Martha, Gutiérrez learned the craft of building a Maloka, a type of communal home built by the Indigenous peoples of Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru. “This changed our way of thinking because it was the first time that we made an offering before building, we aligned with the directions, and prayed that this would be a house of retreat to darkness for women during their moon cycles. Thanks to the cosmological vision of this culture, we understand the need for darkness as a teacher.”

We ducked underneath the low-hanging palm roof to enter the Maloka and sat in a circle on the cool ground around the central fire pit. It was a much-needed relief from the heat outside. The wattle and daub structure featured a ritual table filled with candles and vessels, a hammock, and a small cot. For the walls, Organizmo developed a specific plaster that helps fill in the cracks. She tells us that mastering earth construction is dependent on how well you plaster the buildings and that each region of Colombia (and of the world) has different knowledge on how to do this. “Cracks are one of the reasons why earthen architecture is stigmatized. For plaster, sometimes people use cactus, sometimes egg, sometimes blood, and sometimes cow shit,” she explains.

There are no nails in the entire structure, and it is completely made of green wood such as pine and eucalyptus. “That’s why it is important to have a fire inside because the fire protects the wood and helps it last longer. But the beauty of it is that these types of buildings have community engagement processes where women gather to change the roof.”

Constructing the Casa de Pensamiento

“As we make our way to the next section, Guiterrez points to a series of glowing white domes surrounded by blue and white mosaics. “These domes are a mistake, they shouldn’t live here,” Gutiérrez says. “When you see an earthen dome, it should be in the dessert,” she explains. “But I became obsessed with architect Nader Khalili and went to study at his school in California called CalEarth, where I learned this technique.” The structures are called Eco-domes and are built with an EarthBag building technique (also known as super adobe) using Gaudi-like catenary curves.

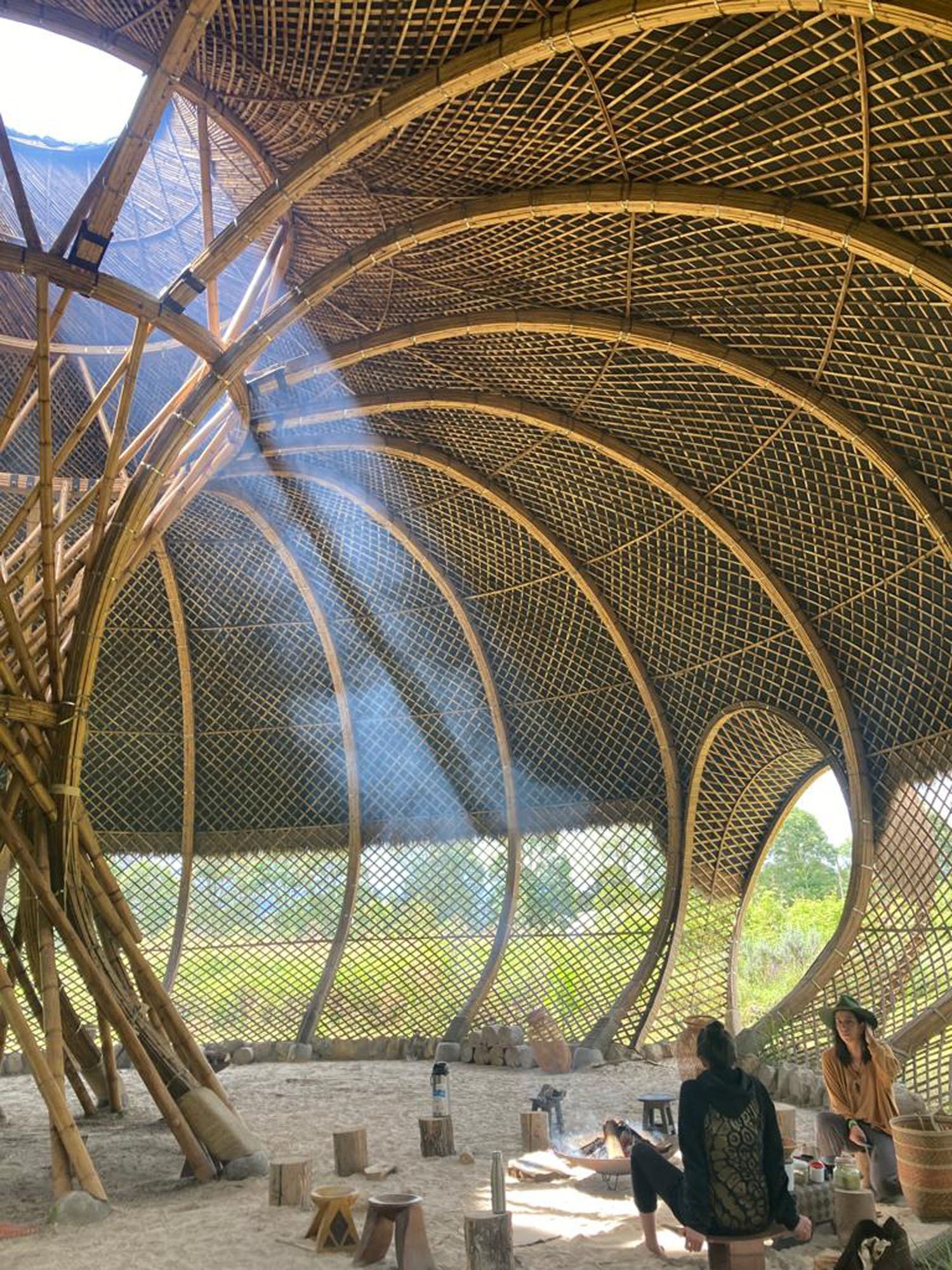

Gutiérrez leads us to the largest structure on the property, guiding us through a specific entrance to the toroid-shaped bamboo-framed building called La Casa de Pensamiento or “The House of Thought.” The building was constructed in collaboration with Jaime Peña Studio and Mexico-based ARQUITECTURA MIXTA, and we were there to meet William Fonque, an agro-ecologist who is going to lead us through a fire ritual. We each take off our shoes and cleanse our bodies with sacred herbs before stepping inside and feeling the sandy floor between our toes. It felt like sitting inside a giant woven basket—and the construction techniques are not all that different.

For Organizmo, all architecture should be deeply attuned to the earth’s cycles. In this way, architecture is the materialization of intention and the cosmological relationship between body and territory. It’s this intentional dialogue and sharing of cultural knowledge that generates new languages and new architectures that prioritize collective visions.

With this in mind, we pass around a burning herbal bundle to smudge ourselves with and then each break off a piece of tobacco leaf to speak our intentions into before casting them into the fire. I whisper a prayer for the Palestinian people in Gaza who have been forcibly removed from their homes and territories, tossing the leaves into the flames.

Creating Space Through Food

“You can’t talk about sustainable habitat or settlements if you leave aside food security or water systems,” Gutiérrez says. In other words, we can’t leave the foundation without trying a traditional meal from the region. We exited the House of Thought through the opposite doorway we came in and made our way to the open-air kitchen where we sat down around a communal table and were served a vegetarian version of ajiaco, a thick soup made of corn and potatoes, served with capers, cream, and avocado, typically found in Colombia, Cuba, and Peru.

Just like architecture, traditional cuisines are manifestations of cultural heritage and contribute symbolic value to a space. The kitchen is one of Organizmo’s craft departments and embodies the “power of culinary knowledge that which words cannot uncover.” Indeed, after eating our meal and sharing stories around the table, I lay in a nearby palm-shaded hammock and thought to myself, how can I possibly translate this experience into words?

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Archtober Invites You to Trace the Future of Architecture

Archtober 2024: Tracing the Future, taking place October 1–30 in New York City, aims to create a roadmap for how our living spaces will evolve.

Projects

Kengo Kuma Designs a Sculptural Addition to Lisbon’s Centro de Arte Moderna

The swooping tile- and timber-clad portico draws visitors into the newly renovated art museum.

Products

These Biobased Products Point to a Regenerative Future

Discover seven products that represent a new wave of bio-derived offerings for interior design and architecture.