October 22, 2024

Ifeoma Ebo Is on a Quest for Urban Healing

Francisco Brown: You work at the intersection of many disciplines—how do each inform the other?

Ifeoma Ebo: I can’t say that I ever sat down and thought, “Oh, I’m going to do this, and then I’m going to do that.” It was about [being part of] spaces of influence. This became clear when I started working in city government after moving back to New York following ten years away. I then worked with the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the Department of Design and Construction (DDC), and the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (MOCJ). These experiences have significantly influenced my current work in other cities, especially with city and public agencies.

For instance, I’m working on a greenway project in New Jersey with Agency Landscape + Planning, a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based firm. We’re trying to introduce a new way of revitalizing this greenway traversing several neighborhoods. Our focus is on community stewardship. Although it’s an infrastructure project and they want green infrastructure, we’re bringing a broader vision. We’re exploring how the city can leverage this greenway to foster partnerships with communities, engage them more effectively, and cultivate a sense of belonging through implementing the greenway.

So, even though the project doesn’t necessarily require a policy-based approach, we’re incorporating that perspective along with a community-driven focus.

FB: What does community engagement mean to you, and is there a good way to practice it?

IE: I try to pause and understand when someone approaches me about community engagement and [ask myself], What exactly do they mean? For me, it is about how you structure a project in the design phase and how you implement it over time. How do you encourage social cohesion through design? What is the community’s role in that design process, and what’s their role in the implementation? It is about how you’re shifting the delivery of that project.

FB: Can you think of an example of a time you received some exciting community feedback?

IE: I’m working on a project on Indiana Avenue in Indianapolis, Indiana. This historic African-American corridor has experienced a lot of cultural erasure over the years. Several plans and “community engagements” have occurred around this corridor for many years, but nothing has materialized.

We had to take space to talk about what has been done before, why people are upset, what the challenges have been, to be really trauma-informed, and to bring those things to the surface so that we don’t repeat them. We want to understand the history and legacy of work around this space, the issues, and why people are fearful. Why is there doubt about the transformation of this place? Then, consider how those fears and doubts can influence the project’s trajectory.

The choice is really about providing someone with a sense of agency so that they have a choice of what they can and want to do. Comfort is about accessibility; it’s about creating welcoming environments. It’s about centering those who have physical impediments, those who might have neurological differences, or even just cultural differences. Trauma-informed design focused on all those aspects, which sometimes may not be considered. Trauma-informed design practice combines those aspects as the project’s main focus and as part of a discussion or a process.

FB: How did you use trauma-informed community engagement in your Flatbush African Burial project and exhibition?

IE: The Reparations in Public Space exhibition is about the Flatbush African Burial Ground as a site that holds trauma in this central Brooklyn community known as the Little Caribbean. This community of color in the Flatbush neighborhood is also an area experiencing rapid gentrification and all the trauma associated with that.

The exhibition was a way for me to process a lot of what I’ve been learning about this burial ground. Brooklyn was a major center for agricultural production, and New York City/Brooklyn was a sizable slaveholding territory. These stories need to be told and learned from. I partnered with trauma-informed practitioner Antoinette Cooper, founder of Black Exhale, to hold a collage and artificial intelligence participatory art-making workshop centering on principles of trauma-informed practice. The images defining spaces of healing were central to the Reparations in Public Space exhibition.

FB: Tell us about the research you’re doing during your new fellowship at the Academy for Public Scholarship on the Built Environment: CLIMATE ACTION.

IE: Honoring open space and just preserving open space is critical to climate action. That’s what my community partner GrowHouse NYC is striving for at the Flatbush African Burial Ground. I am using this fellowship to amplify the work that I am doing with GrowHouse, to activate the burial ground with art and heritage education, and to cultivate a culture of environmentalism among youth in the community. For this community dealing with extreme heat and food insecurity, and with limited access to nature, the burial ground can serve as a resource to learn about land stewardship, which is central to African diasporic and Indigenous culture.

I want to use this fellowship to tell the story of this work, connecting climate action and equity across all neighborhoods.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

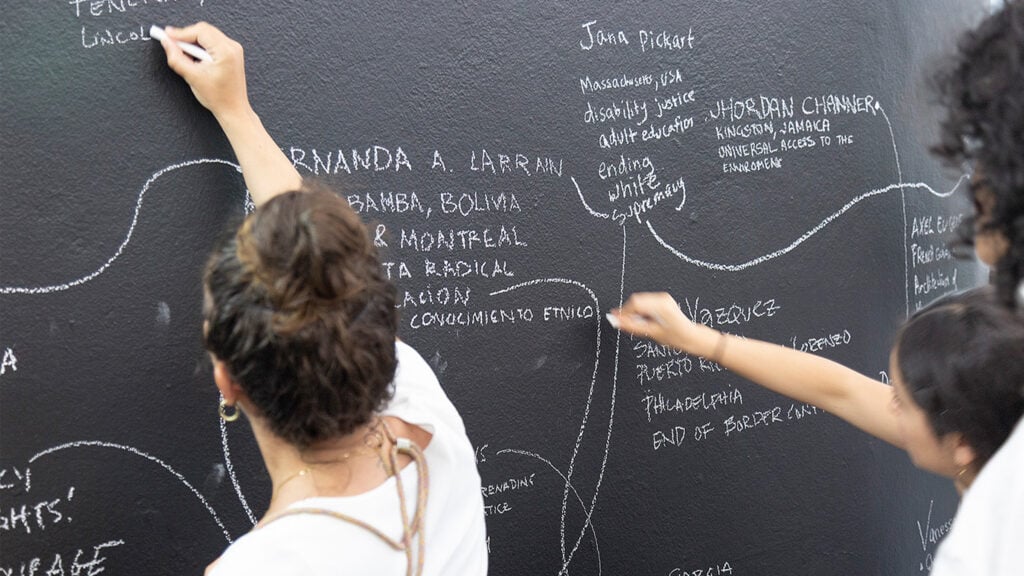

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.