November 1, 2018

Architect Peter Barber Is Reinventing London’s Housing

Barber, the subject of a recent exhibition at the London Design Museum, is creating practical and fantastical solutions for the city’s housing crisis.

Of all the architecture studios in London, none reflect the workings of the practice inside quite so much as Peter Barber’s. Nestled in a Victorian terrace to the east of Kings Cross station, it’s a former printworks with street-facing glazing whose ground floor reception room is a wild jumble of models, sketches, photos, and drawings. Plaster cast streetscapes hang from the wall, jostling with ballpoint scrawls of imagined cities and stacks of Styrofoam housing models encased in transparent boxes—a couple of which are marked with yellow Post-its. The 10-person studio is full of character and ideas, down to earth and open to the city around it. The same goes for its creator, Peter Barber, who towers into the room from a tight, creaking staircase.

The aforementioned Post-its indicate which models are making their way across town to the Design Museum where Peter Barber: 100 Mile City and Other Stories opened earlier this month. The first exhibition in the practice’s history, the show caps off nearly 30 years in the field and a recent flurry of media and professional attention. “It does seem like that,” Barber says. “In the last year it all seems to have been joining up a bit, in some strange way.”

Resolutely committed to housing and a Jane Jacobs view of urban life, the practice finds itself at the center of a renewed urgency around housing in both London bureaucracy and the city’s architecture scene. At a recent event on social housing at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Barber delivered a keynote lecture while his former employer, Richard Rogers, was limited to a five-minute presentation. Rogers stayed for Barber’s lecture, a whirlwind of ideas that joined the dots between Jemaa el-Fna (a public square in Marrakesh whose name translates into “a mosque of nothing”), the narrow lanes of Brighton, Walter Benjamin, London’s abominable homelessness figures, and his own dense housing arrangements that read as much as urban manifestos as homes.

For example, McGrath Road, a 26-unit scheme for the local authority in Stratford, East London, is a “reworking” of traditional back-to-back housing, where separate homes share rear party walls. Prominent in industrializing northern British cities in the 19th century, the typology fell out of favor due to its lack of outdoor space. In Barber’s reworking, the houses are organized in a square, creating a central courtyard as an intimate shared space, while the outward facing houses have deeply recessed frontages beneath swooping arches, creating a private porch. “It’s quite an extreme proposal,” says Barber. The project even comes with an essay titled “Back to Back to Back!” published on the firm’s website which lists “the potential for neighborliness” and high density among this new typology’s benefits.

Viewed from the street, McGrath Road, due for completion this fall, has the same uncanny presence as much of the practice’s built work. At first glance, the tone of the bricks and mid-rise elevation imply a regular new London vernacular—the conservative style dominating new build housing across tenures and across the city. The detailing of Barber’s project, however, feels more European. The double-height archways betray a hint of the Amsterdam School, while French doors beneath the chamfered lintel of a top-floor window provide generous natural light inside. What’s more, there’s not a pitched roof in sight. Instead, rectilinear forms dominate—in homage to one of Barber’s heroes, Luis Barragan. The building looks like home, it looks like London. But it’s somehow a different London, a London we’ve not yet arrived at.

Projects across the city bear variations on the Barber signature, blending the vernacular and the adventurous; the social and the sturdy. Long devoted to building housing, Barber’s practice is currently leading a charge of renewed house-building initiative from London’s borough councils and Sadiq Khan’s Greater London Authority. Two affordable projects for local housing authorities—Ordnance Road, a row of townhouses in Enfield, north London, and Worland Gardens, another in Stratford—also feature staggered brick facades and arched porches: “A sunny spot for people to have a cuppa,” according to Barber. Moray Mews, a new cobbled street with eight houses for a private developer in Finsbury Park, includes a brick bench that appears to fold out of the alley itself. The windows of Donnybrook Quarter, a prize-winning project from 2006, are oriented towards a tree-lined, pedestrianized micro-plaza. One juts comically out of a curved corner in its rectilinear frame, as though reluctant to miss out on the action below.

When he presents Donnybrook Quarter, Barber often mentions the front door windows that have been covered with posters and patterns by their residents for added privacy. It’s an act of customization that delights Barber despite the design error they reveal. As he put it in a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society last year: “Projects like Donnybrook Quarter contain housing but more fundamentally they are a celebration of the life of the city.”

This is emblematic of Barber’s approach to architecture in general. Despite the technical proficiency with which he imbues each project—particularly in their complex arrangements to heighten density—there is a sense that Barber and his practice are more interested in the intangible, even emotional, aspects of life, those which are facilitated by architecture, than the nuts and bolts of a building in itself.

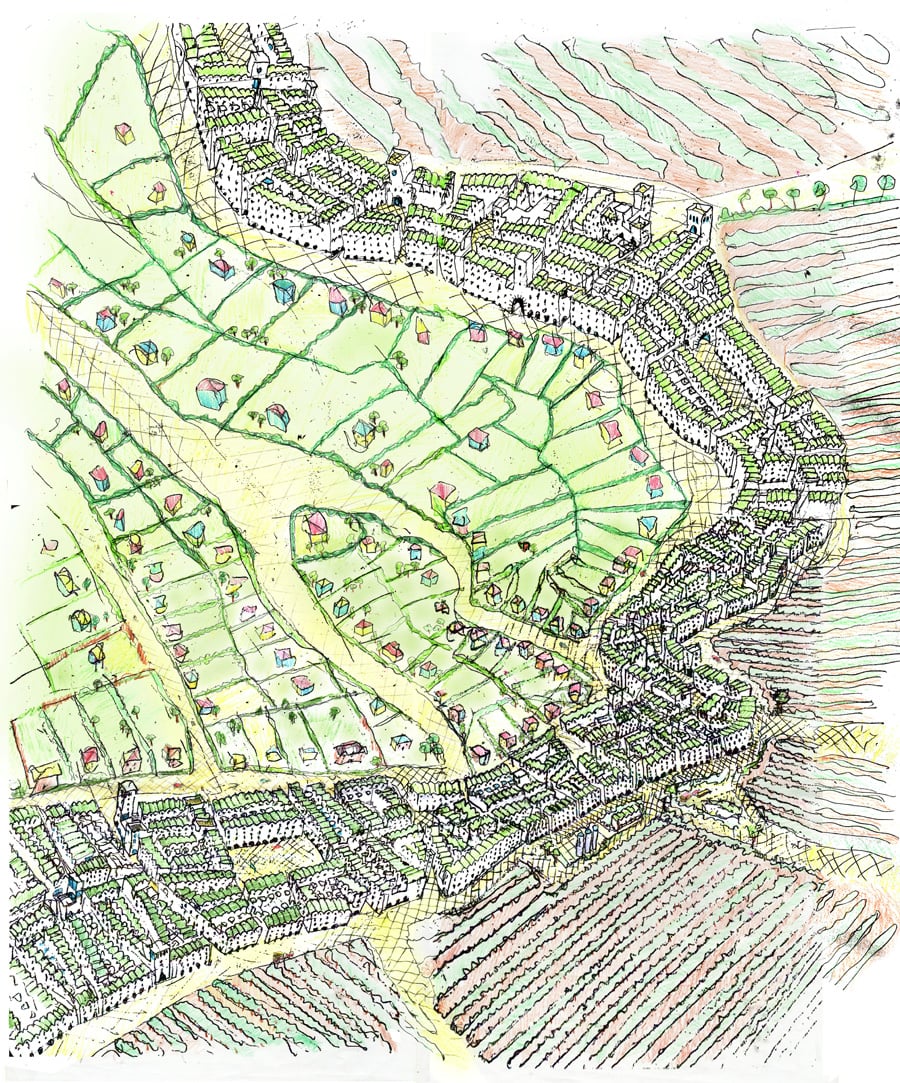

Nowhere is this made clearer than in his speculative work. Highly provocative and largely unfeasible, Barber is constantly sketching projects: imagined housing, lost villages, and fictional cities which are showcased on his Instagram, One Year 365 Cities, some of which resemble built projects. “I’m trying to imagine things being better, and not feeling always constrained by the system, the economy and the culture which exists right now,” he explains.

100 Mile City, for example, is a concept that Barber has previously explored in drawings and models, and is elaborated in a new short film at the Design Museum. The proposal is for a linear city that wraps around the edge of London’s green belt, radically densifying the outskirts in order to solve the city’s housing crisis that currently sees 120 families lose their homes each day, all connected via a “super-functional, super-fast, and super-fun” monorail.

It’s a wild plan but it’s highly attractive. Who wouldn’t want to solve the housing crisis? Who wouldn’t want to see the suburbs turned into a thriving labyrinth of streets, part-Porto and part-Paddington? Who wouldn’t to ride the monorail of the 100 mile city? Perhaps more wild, however, is its close relation to the practice’s forthcoming projects. Barber jokes that an upcoming residential project on a strip of the North Circular Orbital road could be the first piece of an alternative “62.7 mile city,” in reference to the length of London’s primary ring road. Ever grounded in the reality of his built projects, Barber still allows his mind to wander, pushing at the constraints that have defined architecture throughout its history.

“I think it’s good, from time to time, to step outside a different set of constraints. Imagine a world in which we’re building 150,000 social houses a year,” he says, back in his Kings Cross studio, surrounded by models of homes and visions of a London still to come.

You might also like, “KKE Architects Fosters Warmth and Tranquility at New Hospice Facility in Wales.“

Recent Profiles

Profiles

Chris Adamick Designs for Life