February 10, 2021

Q&A: Mariana Mogilevich on New York City’s Path to a More Democratic and Diverse Civic Realm

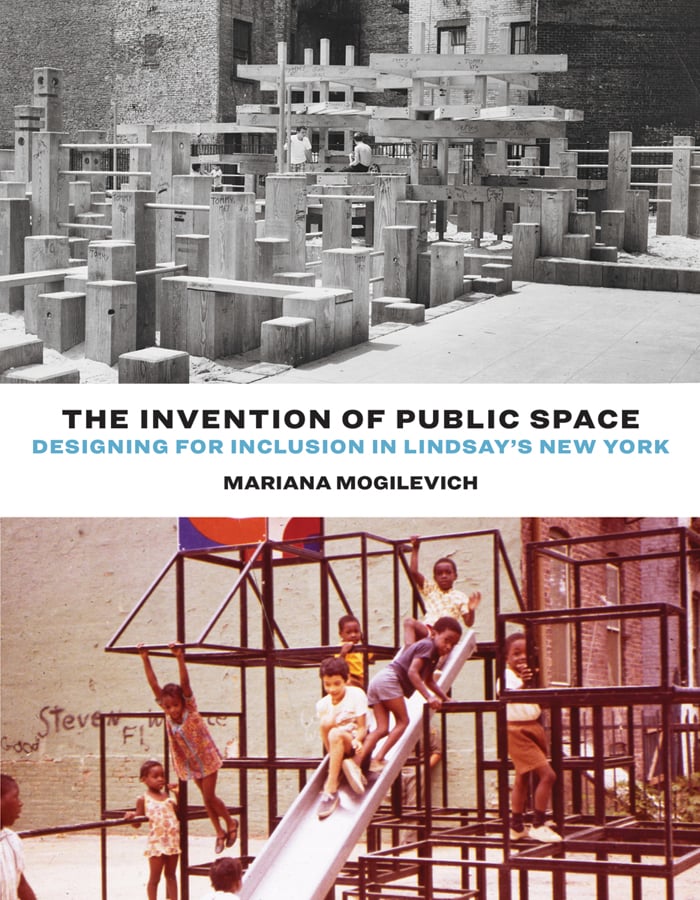

Upon the release of her book The Invention of Public Space, the architectural historian discusses a little-known but pivotal chapter of urban history.

John Lindsay is not the most revered or famous mayor of New York City. His politics were fairly tepid and his background somewhat ordinary. But his attention to public spaces and diverse communities has left an unmissable mark on the city’s built forms and the ways its residents use, experience, and reshape the public realm.

The Invention of Public Space: Designing for Inclusion in Lindsay’s New York, a new book from architectural historian Mariana Mogilevich, argues this point of view in depth, highlighting the politics and negotiation inherent to this chapter of New York’s history. Mogilevich, who is the editor in chief of the Architectural League’s editorial imprint Urban Omnibus, shows how Lindsay’s mayorship came at a transitional moment in global design practice and theory, when considerations of psychology, identity, and community could no longer be ignored and increasingly informed the design of the public realm. Not unlike today, it was an era defined by profound demographic and cultural shifts, which in turn drove new uses and perceptions of urban space, and where optics, micro-politics, and “on the ground” realities were hardly beside the point.

Metropolis spoke with Mogilevich about this moment in urban history and how its legacy continues to be readapted and reassessed today.

Why did you decide to focus on this character from New York’s history?

Lindsay came into office at the height of what we call an age of “urban crisis.” The book is really about the period of time and the set of questions that designers and urbanists were grappling with: What did the city have to offer when people were moving to the suburbs in droves? Or how could the built environment include people who had been excluded from public life across racial lines? He made possible this really important period of experimentation to address those questions.

Can you talk about some of the urban conditions and conversations that were going on as he was taking office? How was the stage set on the eve of his election?

One way of looking at it is the fall of the age of urban renewal, which is often associated with the figure of Robert Moses. His approach was coming under criticism as top-down and exclusionary, and the environments it produced were seen as alienating. There was so much pressure building for inclusion and bottom-up participation. So what do you do instead? That wasn’t just a New York story, but a global question. And a lot of that new approach centered on the things that we call public spaces.

There was a lot of attention given to streets and parks and plazas: What’s the relationship between public spaces and a certain kind of urbanity? This is connected to questions of how and where people are free in urban space. Thanks to the civil rights movement, and then the women’s and gay rights and other social movements, there was a growing understanding that public space had been defined and designed in the image of a homogenous public. Access to those kinds of spaces had been restricted and they maybe did not even provide a diverse public with what they needed.

I wonder if you think that shift correlates with a growing awareness of the role of identity in the public realm.

There’s absolutely a focus on how these spaces are going to be used and who is going to use them, understanding that there’s difference—culturally and socially—among those different types of users. But it’s not just recognizing difference; it’s also about distribution. There was a reaction to the fact that public goods have largely been distributed to one segment of the population: white citizens. So how do you expand not just access to the public realm, but address where these parks are, so that they can become places where everyone can use and exercise their rights.

What and who were some of Lindsay’s specific policies and collaborators?

Lindsay tried to show through the city’s public spaces that New York was fun, that it was for all the people. Some of that was in new designed spaces, and some of that was performative. For example, he closed down Central Park to car traffic and would be photographed biking there. He’d go out and walk through the streets in neighborhoods that other politicians did not pay attention to.

A lot of the most interesting developments were in city parks. Lindsay’s first parks commissioner, Thomas Hoving, was really serious about putting new projects in areas that had been overlooked and worked with exciting young designers like Paul Friedberg and Richard Dattner. The city built things like adventure playgrounds in small parks across the city, which were challenging the idea of standardized equipment for standard experiences—they’re really architectural terrains for kids to use however they want. But they were also models for larger-scale ambitions to transform the city’s open spaces.

You dedicate an entire chapter to Lindsay’s work on pocket parks, and it seems there’s this big slippage or disconnect between planners and the people that they’re working with. What are some of the takeaways from that saga?

It is important to note that they’d never done this before. There weren’t structures in place, so you get really interesting questions about what participation is and how it should happen—from site selection to developing designs, to who’s actually going to take care of a park once it’s finished. I think there was conflict and confusion at every step because it is so undefined. It opened up all these questions—still unresolved today—about how you square local knowledge and needs with professionals’ expertise and with bureaucratic boundaries.

You did all this research before 2020, which had two very big upheavals that implicated public space quite directly, one being the protests for racial justice and the other being the pandemic. Did these developments change or augment some of your castings of public space in the book?

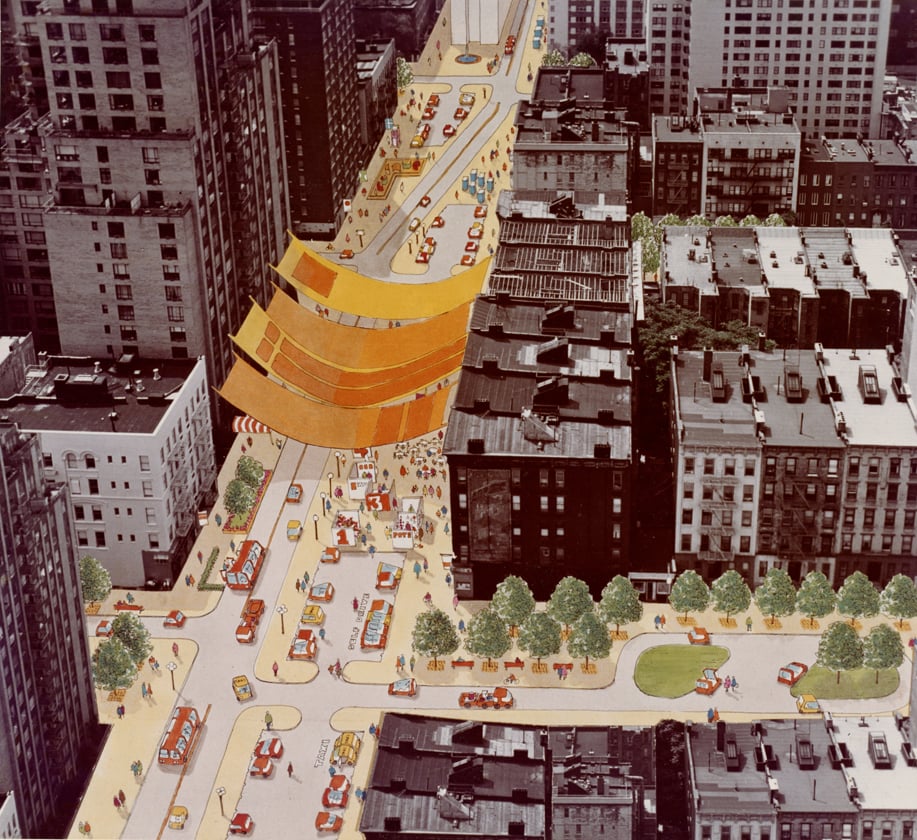

We don’t know yet the public space repercussions of what we’ve seen in the last few of months, but there is an opportunity right now to learn from these earlier experiments and try to do better. The Lindsay administration’s street closings in the early 1970s look very familiar now, but there was a perversity to them: The streets were the site of so much political mobilization, but then were turned over for much less political uses as sidewalk cafes and a way to attract office workers. Yet people still interpreted these pedestrianization projects as a radical political move, seeing something inherently democratic about just people being out on the streets. I think those associations have really stuck. For example, the street closings that began as a way to address the lack of access to parks and open space during COVID quickly became a conversation about sidewalk dining and the survival of businesses. I think we need to try to not collapse all of these different concerns into one physical solution that pretends to take them all on.

What lessons from this era can practicing architects and landscape architects apply in their own work?

One really important thing is to not assume that if something can be called public space, that’s an automatic and unproblematic good. We have to continue to think about what type of public is being included and imagined in that work.

So one lesson is to embrace, or at least accept, that complexity and not expect a simple solution. I think that is a really critical to be aware of the complexity, and to continue to muddle through that difficulty. It is so complicated precisely because of the larger social questions that are wrapped up and play out in each project, at each site. But you can look back to things that have been tried, to different ways of making space that can push things in a better direction.

You may also enjoy “At Dallas’s Hall of State, a Return to Majesty”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Profiles

Profiles

Chris Adamick Designs for Life