September 20, 2018

It’s Robert Venturi’s World—We’re Just Living in It

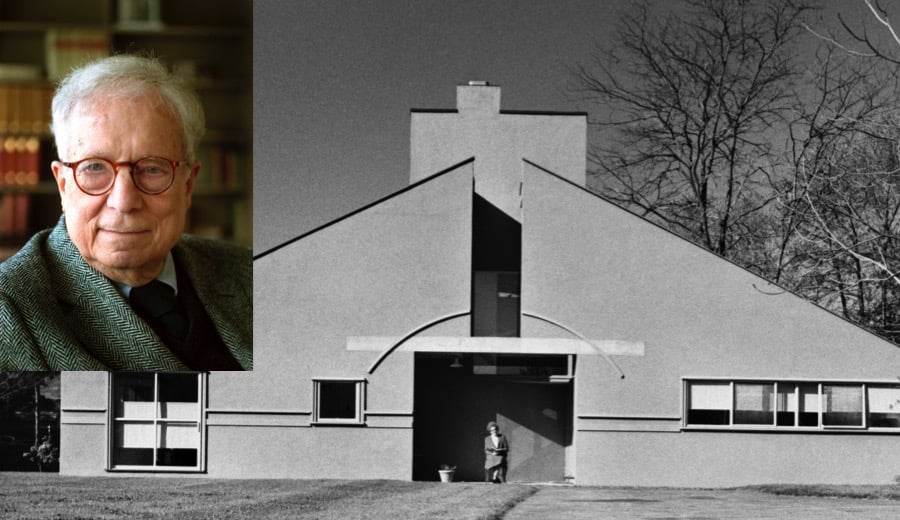

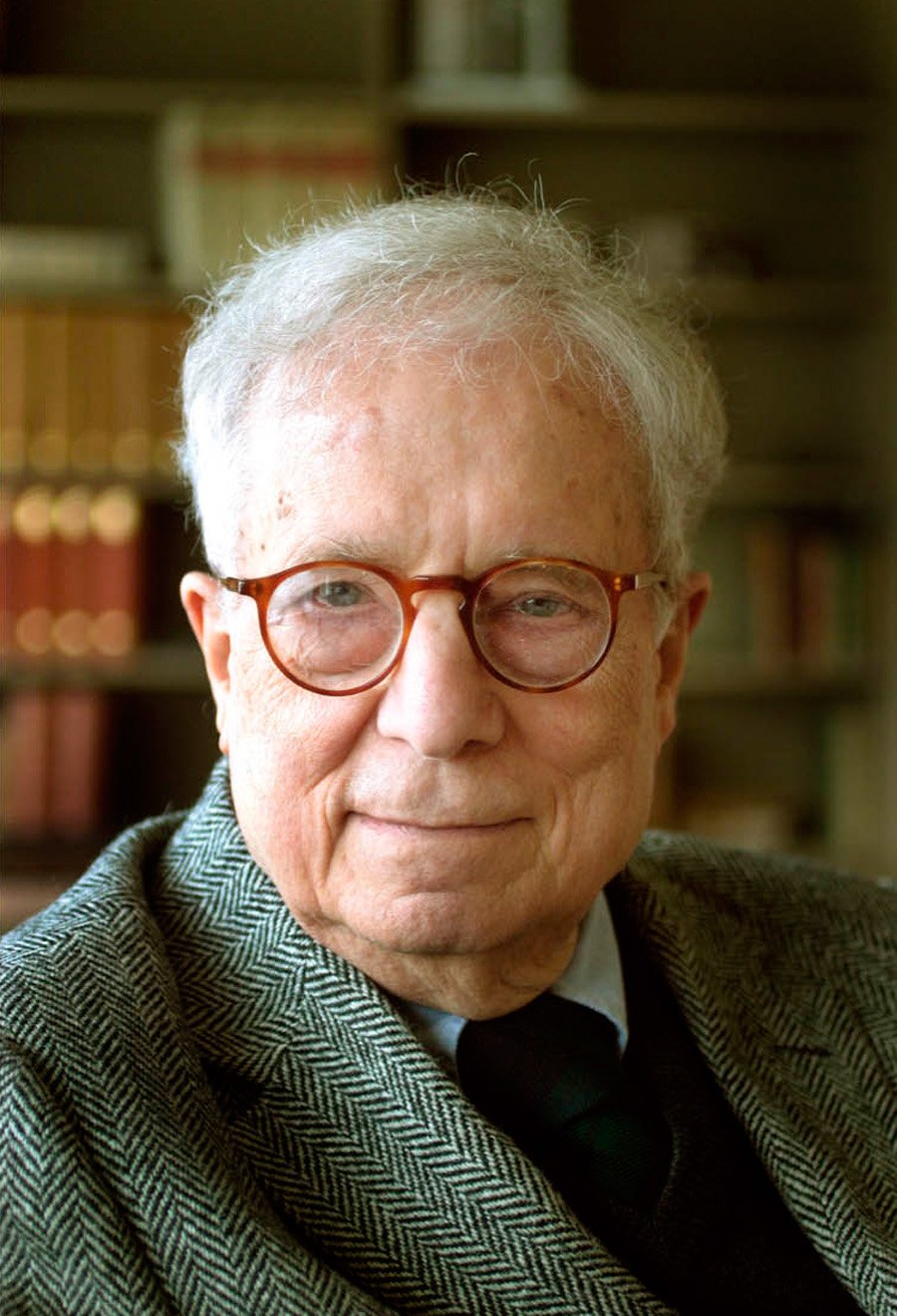

Remembering the influential life and career of architect Robert Venturi, who died at the age of 93 Tuesday in Philadelphia.

When Robert Venturi famously quipped in his seminal 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture that “less is a bore,” he not only coined an ever-quotable rejoinder to Mies van der Rohe’s maxim “less is more” and midcentury Modernism generally, but articulated an ethos that was at once contrarian and powerfully prescient.

Venturi, who died Tuesday at 93 after a brief illness, spent a career criticizing and arguing against Modernism’s ordered simplicity. As a generation of architects and observers fetishized van der Rohe’s steel-and-glass buildings and Le Corbusier’s superblocks and cruciform towers, Venturi had his sights trained elsewhere. An architectural analog to photographer Walker Evans, Venturi was fascinated by the American strip, neon signs, suburban architecture, highway infrastructure—the ordinary elements of everyday lived experience that earned scoffs and upturned noses from his contemporaries.

“Main Street is almost all right,” he wrote.

“I’ve always had a great fondness for that lovely line, it was almost lyrical in a certain way,” critic Paul Goldberger tells Metropolis. “He’s not saying it’s literally alright, but almost alright—more alright than we thought it was—and what can we do to make it better? ‘Main Street is almost alright’ as opposed to ‘Main Street should be bulldozed and replaced with a shopping mall.’”

It’s a concern that many might not have been ready to address 40 or 50 years ago, but it’s one that’s central to the conversation today. It’s impossible to look around any street, or drop in to architecture Instagram or Twitter, and miss Venturi’s influence in what is being built, photographed, and fetishized. “It’s like the world is finally catching up with him,” Goldberger says.

Born in in Philadelphia on June 25, 1925, Robert Charles Venturi, Jr. studied at Princeton and worked in the offices of Eero Saarinen, Louis Kahn, and Oscar Stonorov before opening his own practice in 1960, first with William H. Short then John Rauch. His first major commission was Philadelphia’s Guild House, a six-story, 91-unit red-clay-brick low-income housing development for senior citizens built in 1964 and conceived “to be ordinary and monumental at the same time,” Venturi told John W. Cook and Heinrich Klotz in their 1973 book Conversations with Architects.

Also completed in 1964 was the Vanna Venturi House, a five-room home he built for his mother. At 30 feet tall, the house seems constructed out of a giant roof (a sly riff on vernacular architecture that would play a major role in Venturi’s career) and, together with the Guild House, signaled a break from Modernism. Critic and friend Vincent Scully called it “the biggest small building of the second half of the 20th century.”

Just don’t call it Postmodernism — a term he vehemently rejected. Staring out from the cover of the May 2001 issue of Architecture magazine, Venturi declared “I am not now and never have been a Postmodernist.”

Venturi also taught at the University of Pennsylvania where, in 1960, he met fellow architect and professor Denise Scott Brown, who would become his most vital partner and collaborator. They were married in 1967, and she joined Venturi Rauch in 1969. Together they worked on Fire Station No. 4 in Columbus, Indiana (1968), the Trubek and Wislocki Houses (1972) in Nantucket, the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery of Art (1991), and the Seattle Art Museum (1991), among other sophisticated and iconic projects.

But perhaps their most important project was the 1972 book Learning from Las Vegas, which took a sociological, serious view of a place and mode then dismissed as crass and unworthy. Scott Brown introduced Venturi to Vegas, and it was there that they “could discover the validity and appreciate the vitality of the commercial strip and of urban sprawl, of the commercial sign whose scale accommodates to the moving car and whose symbolism illuminates an iconography of our time,” Venturi said in his 1991 Pritzker Prize speech. “And where we thereby could acknowledge the elements of symbol and mass culture as vital to architecture, and the genius of the everyday, and the commercial vernacular as inspirational as was the industrial vernacular in the early days of Modernism.”

“In Learning from Las Vegas, they were out there on the streets looking at parking lots and talking to students and really understanding the way people lived,” Avery Trufelman tells Metropolis. Trufelman, a producer on the podcast 99 Percent Invisible, recently devoted an episode to Venturi, Scott Brown, and Vegas. “They have this kind of romantic love story at the same time they were very tremendous, furious collaborators,” she says. “They are peanut butter and jelly. They are so great in their own right and they just do magic together.”

Venturi retired in 2012, rebranding Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates as VSBA Architects & Planners, but his impact never waned. Rather, it has become more pronounced. Through books like Complexity and Contradiction and Learning from Las Vegas and in buildings like his houses, Venturi married a kind of Pop art, kitsch-embracing sentimentality to the built environment. When the architectural zig was sleek order, he zagged. And just as art and culture trends seem to play perpetual catch up to Warhol, Venturi will forever be just a bit further ahead, beckoning from a world that’s finally coming into focus.

You might also like, “Denise Scott Brown’s Photography Celebrates ‘Messy Vitality,’ Pop Art, and Everyday Architecture.”

Metropolismag.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program and earns from qualifying purchases on amazon.com.

Recent Profiles

Profiles

Chris Adamick Designs for Life