September 20, 2021

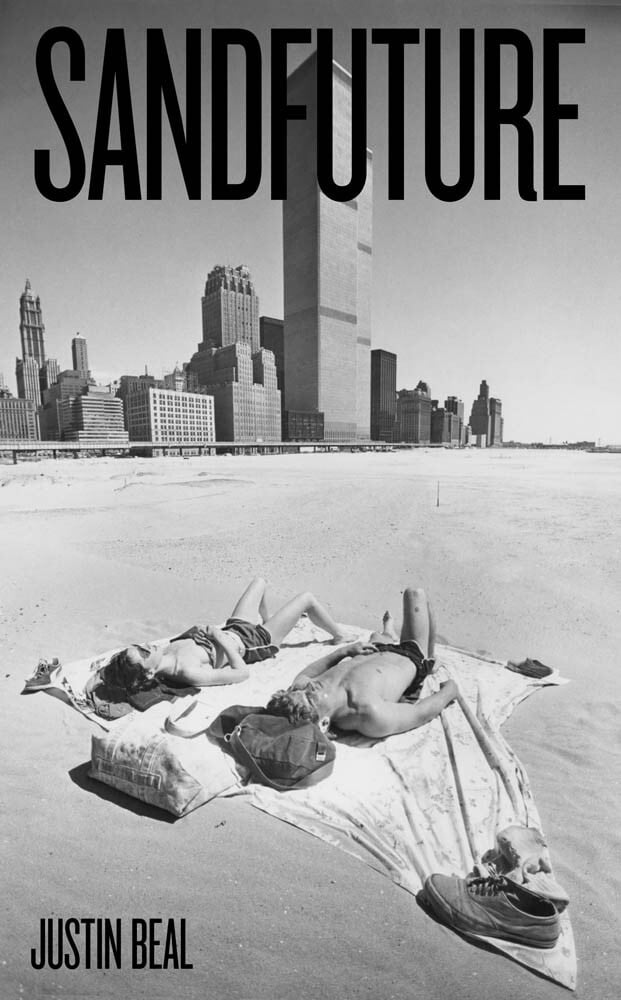

Sandfuture, an Unconventional Biography of Minoru Yamasaki, Pushes the Boundaries of Architectural Writing

MIT Press, 256 pp., $24.95

Available for preorder

JL: Why do you think Yamasaki is so unappreciated and unknown?

JB: I think that’s a complicated question. I think it’s tempting to first consider it an issue of race, which I think it very much was. Architecture is not a diverse profession, never has been and especially at the time when Yamasaki was practicing, it was really dominated by a certain kind of white man of privilege. That was a force both invisible and visible that he was fighting against his entire career. But I also think he encountered a different kind of marginalization, one that can’t really be disentangled, which has to do with his approach to ornament and decoration at a time when modernism was very opposed to both. Also, the fact that he was in Detroit and not in a traditional center of academic architecture—all these things conspired against him, even before the early 1970’s when the failure of Pruitt-Igoe (a St. Louis housing project Yamasaki designed in the 1950’s that was demolished by government directive by explosives in the 1970’s) and the critical rebuke of the World Trade Center ultimately contributed to his marginalization.

JL: What lessons can architects today draw from Yamasaki’s professional and life experiences?

JB: In Yamasaki’s case, he tried really, really hard with Pruitt-Igoe and with the World Trade Center to make the most humane projects he possibly could, even though the circumstances made it virtually impossible to achieve that. His idealism is probably his most modernist characteristic. He was trying so hard, in the case of Pruitt-Igoe and the World Trade Center in particular to make the most of these incredibly rigid, bureaucratic programs. Of course, I think he fell short in both cases. The tragedy of his story is he was incredibly prolific—he made a huge number of very adored buildings, but he is by and large remembered for two spectacular failures.

Another way to answer that question would be that it’s remarkable how little people have learned from the failures of the World Trade Center. I think about it the few times I’ve had to go to Hudson Yards, which really makes many of the same mistakes as the World Trade Center did at a really basic level, of imposing unwanted office space on a city that doesn’t need it, of having a giant plaza open to the wind coming off the Hudson River, of building at a scale that is grossly disproportionate to human occupants. If anyone had considered the story of the World Trade Center when they were conceiving Hudson Yards, I would hope that they would have approached it differently.

JL: How, if at all, will you commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11?

JB: I really find it’s so unfortunate what those buildings have come to signify. When I first encountered them, I thought they were really so spectacular as objects. I find that the way that they’ve come to a signify a certain kind of American unilateralism is really unfortunate. I think my only contribution to that is to being able to try to tell a little bit more about Yamasaki’s story—if people understood where he was coming from as a man who was a child of immigrants in Seattle, had to help his parents escape internment and worked against endemic racism his whole life to kind of build these buildings that he really believed, as absurd as it sounds in retrospect, as a sort of symbol of world peace, how unfortunate it is that they’ve come to symbolize something quite the opposite. Which I guess is a long-winded way of saying I am probably not going to do anything in particular to commemorate the anniversary.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

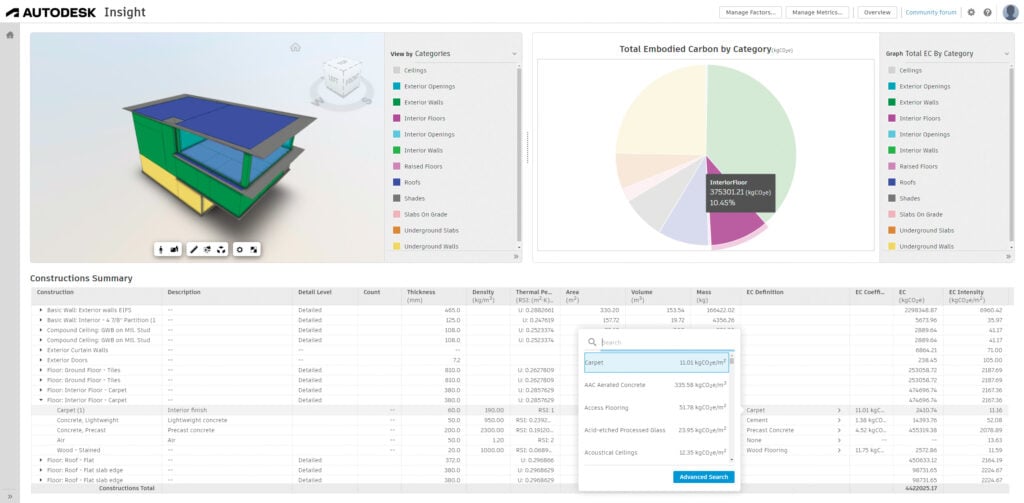

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.