September 1, 2022

A Brooklyn Fitness Center Aims to Support a Community Threatened by Gentrification

By “us,” he means BFC Partners, the real estate and development company for which he serves as director of community engagement, and by “they” he means the Legal Aid Society, who, with the support of New York Communities for Change and the Crown Heights Tenants Union, sued the city over the project in 2017, claiming that the city and BFC had not properly studied the potential displacement a renovation of the Bedford-Union Armory could cause. Abutting two housing buildings, one of which was originally slated to be market-rate condos, the Major R. Owens Health Center threatened displacement in an already gentrifying community. Laurie Cumbo, the city council member who brokered the deal between the city and BFC when the project was first conceived, went so far as to at one point withdraw her support when the developers wouldn’t increase the percentage of affordable housing.

Nearly four years after the lawsuit and ensuing controversy, the health center opened in the fall of 2021 after a functional renovation by architecture firm Marvel. “The sustainable portion is that we’re reusing a building that’s over 100 years old. There weren’t any major lifts or any huge interventions; we were able to work with a lot of the existing spaces,” Marvel principal David Jackowski says. Marvel’s work is indeed subtle and thoughtful: handrails have been brought up to code via additions that neither mimic the old nor stand out as too new. In the lobby, the building’s original repetitive structure serves as a container for small offices, defined by simple metal and glass partitions. The supporting structure in the armory’s drill hall soars but doesn’t distract, and the interiors of each space—the swimming pool operated by Imagine Swimming, the dance studios run by Ifetayo Cultural Arts Academy, the basketball courts and homework help program run by New Heights NYC, among others—all speak different aesthetic languages but understand each other, a testament to the designers’ ability to make room for the identity of each group that uses the space.

The health center currently houses eleven tenants, nine non-profits and two for-profits, and Woodlin insists that they provide services that this community wouldn’t otherwise get. Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator with Housing Justice for All, told me that despite the services housed in the building and the improvements to the housing affordability (one building is fully affordable housing, and the other is half affordable and half market-rate), the project is still a “good example of the city having a really strong hand to negotiate with a developer and refusing to use it.” Last year, Gabriel Sandoval of local news outlet THE CITY reported that only 250 memberships are reserved at the discounted community rate—in an area where about 45,000 people would qualify. Despite its communitarian efforts, BFC is still a for-profit developer, and a project like this will always prioritize its bottom-line, no matter how thoughtful and considered the architectural interventions.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

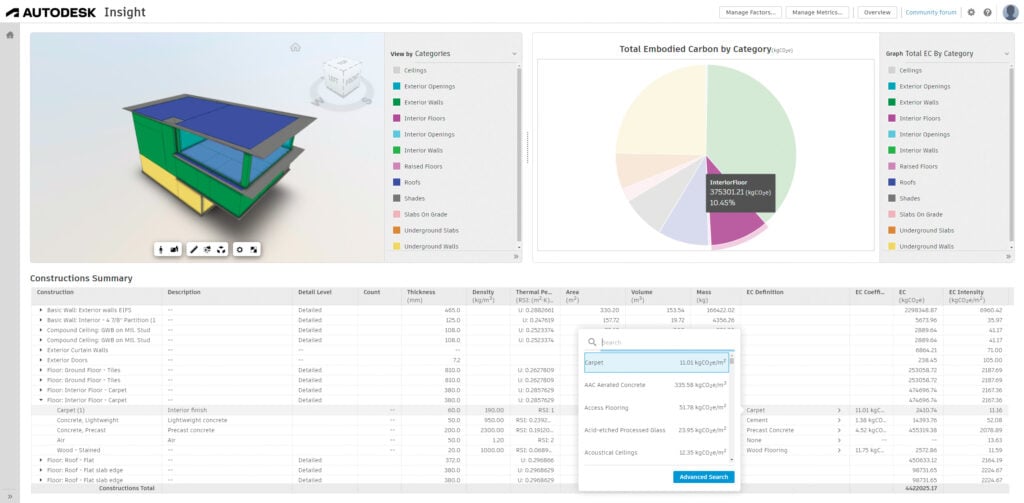

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.