March 6, 2023

Eric Owen Moss Architects’ (W)rapper Building Rises in Los Angeles

For more than 40 years, Eric Owen Moss Architects and developers Samitaur Constructs have been creating a compilation of more than 30 rugged, deconstructed structures at Hayden Tract, a former heavy manufacturing hub in Culver City, California. The stream of experimental edifices—many filled by creative and tech firms—have short, catchy names like Pterodactyl, Beehive, Dune, Stealth, Waffle, and Umbrella.

As the area has filled up, it’s begun expanding eastward (along with a number of unrelated projects) across Ballona Creek into Los Angeles, where yet another mini city is starting to aggregate near the La Cienega Expo Line light rail station, which opened in 2012. By far the biggest building of the bunch (its height allowance came thanks to the addition of transit in the area) is the recently completed (W)rapper, a 17-story, 235-foot-tall tower that initially gained approval back in 2001 but was delayed by a series of setbacks that included the 2008 recession and a multi-year peer review necessitated by the fact that the planning department had basically never seen anything like it.

Developing (W)rapper’s Stunning Structure

(W)rapper’s design grew out of a 1998 installation called “Dancing Bleachers,” which Moss’s firm completed at the Peter Eisenman–designed Wexner Center in Columbus, Ohio, responding to that building’s omnipresent square grids by employing a series of grids based, in contrast, on curves. So the new tower, which first took shape the same year, became about shifting a building’s typical structural grid of columns and beams into one based on curving external bands.

“As soon as you bend that column line, the framing becomes substantially different,” explains Moss. “It’s a conceptual tension between the possibilities of disorder and the promise of order.” Moss sees the building—like most of his work here—as a resounding counterpoint to the glassy, orderly blocks that most offices inhabit.

Expressing the Logic of the Building

When you first look up from the corner of Jefferson and National Boulevards, the gray tower shoots up from its relatively flat surroundings like a launch pad crossed with a gargantuan tree crossed with an ancient ruin. Its mélange of rough, two-coat plaster frontage, tinted and gridded window wall system, and arching structural steel bands (each is a foot thick and five feet tall, coated with spray on cementitious fireproofing), looks somewhat arbitrary. But it’s in fact quite rigorous, growing out of the ever-shifting, arched bands, their loads transferring from band to column to girder and creating increasingly complex building geometries. (3D survey tools were particularly essential for construction.) After some time, it starts to make sense: It’s a building that is entirely driven by its unorthodox exterior structure.

“We tried to take the logic of the building and express it,” confirms firm project director Dolan Daggett. “Once you combine architecture and structure it changes everything.”

An Aerie for L.A.’s Tech Scene

Because the building’s structural elements are located along the exterior, and the elevator core is shifted to the south, massive interior spaces on each floor are almost completely open, with no internal columns or drop ceilings. Add to that a combination of slightly warped walls and wraparound views and one gets the impression of floating in a nest. You can feel the structure around you. The arcing bands frame views in ways you’d never expect, and on lower levels the passage of Expo Line trains lends a dynamic, urban feel that becomes somewhat surreal when you watch the trains curving around the bend, seemingly swallowed by the expanse of the Los Angeles Basin. Floor heights range from 13-and-a-half all the way to 24 feet. All column loads progress down to just three exposed base legs, supported by a base isolator, making the building highly earthquake resistant. (With its VRF HVAC and copious natural light, the building would have achieved a LEED rating if the architects had pursued it.)

The tower, softened at ground level by light landscaping and a water feature formed from modular landscape paver blocks nicknamed the “Puddle,” seems appropriate for creative tech firms looking for lofty, light-filled, varied, and unquestionably unusual spaces combined with sweeping views. The firm is hoping to build three more unconventional towers in the immediate vicinity—named Turtle, W2, and Trajan’s Tower—and has already received city approval for two. But first comes the question of whether tenants will occupy this one. Moss and Samitaur have a good track record, which Moss attributes largely to the late Samitaur co-founder Frederick Samitaur Smith (his wife Laurie now leads the company).

“He wanted to put unconventional architecture on the street. He looked at it as saleable; that it would attract a certain kind of tenancy,” says Moss. “It suggests quite a different business model for development than the conventional stuff. If you make it work, it suggests it’s not as hard as people thought.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Projects

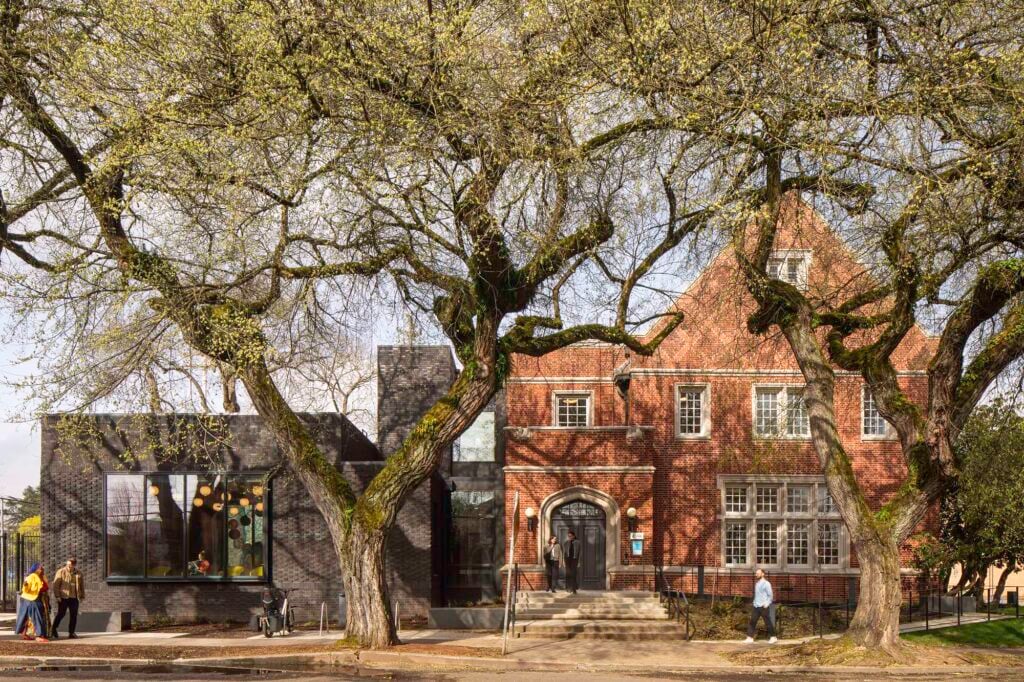

Portland’s Carnegie Libraries Reopen as Community Anchors

LEVER’s transformations of the Albina and North Portland libraries expand their civic role—pairing preservation with cultural investment and community-led design.

Profiles

Tuckey Design Studio Is Rooted in Reuse

Throughout design and construction, the London-based studio takes a circular, materially sensitive approach to both adaptive reuse and new builds.

Projects

A Historic California Schoolhouse Becomes a Home for Quantum Research

EYRC Architects restored Orange’s Mission Revival Killefer School, preserving its layered past while adapting the century-old landmark for Chapman University’s Institute for Quantum Studies.