December 4, 2017

Frank Lloyd Wright Redesigned the Suburbs—Today’s Architects Should Do the Same

Architects may not like it, but sprawl isn’t going away. Frank Lloyd Wright not only understood that, he dared to reimagine it.

The central issue facing the world of architecture today is sprawl. Surprisingly, the last architect whom both professionals and the general public took seriously to offer a comprehensive solution to the spreading of urban environments was Frank Lloyd Wright. Already in the 1920s he had realized that the megapolis had extended so far beyond its traditional core, which he respected but did not like, that its far reaches had become completely mixed with rural elements. Though we may disagree with the nature of the plans he presented in Broadacre City (conceived circa 1929, first shown in 1932, and developed throughout subsequent years), as well in his earlier proposals for suburban communities in Oak Park, Illinois, and his later Usonian houses, at least he accepted the reality of suburban developments such as the one he inhabited. He took seriously the way Americans live, at the time in radial communities connected to a downtown, but which he already saw reaching far beyond such hub-and-spoke urban constructions, and thought that architecture could make it better.

These days, architects tend to ignore sprawl. That is probably because those architects who see themselves as responding in a critical way to the built environment live in the urban cores whose essential goodness is now something we accept as a fact. Only very few theoreticians, most notably Robert Bruegmann (Sprawl: A Compact History, 2005) at the University of Illinois at Chicago, have tried to make sense of sprawl without dismissing it. In Houston, Lars Lerup and Albert Pope at Rice University developed ways to give names to sprawl that articulated its inherent forms (“ladders” for Pope, and “stim and dross” for Lerup). The Southern California historian Alan Hess has honored such historically important developments as the Irvine Ranch early subdivisions with insightful writing. Younger voices like Alan Berger, author of Drosscape (2006), have argued that we need to understand the history and logic of suburban and exurban development so that we can figure out how to act in a responsible, critical, and productive manner within its reaches.

We need to look beyond our urban cores because sprawl is not going away. The financial crisis of 2008 led to a dip in home building and net out-migration from downtowns, but the trend has now reversed itself back to the norm of continual expansion that has held true since before the Second World War. Although the Brooklynization of cities all around the country and world has received a great deal of press, let’s remember that, for all the streetcars and cappuccino bars serving the young and wealthy, these new downtown scenes present only a tiny fraction of urban sprawl. In Phoenix, where I live, they dream of 60,000 people living downtown—of a population of over four million in the metropolitan area.

I would propose that we indeed look at sprawl seriously, and that we use some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s insights to do so. We can turn to earlier examples of regional planning, such as Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, and find European examples of thinking about sprawl throughout the century, but Wright remains the source of the most original American model. What can we learn from Wright’s ideas and suggestion to make sprawl work from a social, environmental, and aesthetic standpoint? Is there anyone taking his work forward?

First, Broadacre City shows a respect not only for the Jeffersonian grid, but also for the democracy it sought to spread throughout the American continent. Wright imagined not so much a utopia as a refinement of the grid into nodes of trade and culture spread out through a landscape of farms that were also suburban-style homes. Following the ideals John Ruskin first articulated in The Two Paths, Wright believed that society should consist of communities that would collaborate to exchange craft and sustenance. The city, with which he had a love-hate relationship, would remain only in fragments, as a scattering of apartment buildings, small offices, train stations, schools, and cultural and sports facilities.

This is, in fact, what most of the United States looks like today—without the actual self-reliant communities Ruskin and Wright thought would emerge. The cities, although they have not withered away, have grown by dispersing into the landscape, leaving cores that are the command, control, and cultural centers for a region. Now we are seeing more proposals for urban agriculture and homesteading in cities such as Detroit, where homes are being renovated in the middle of productive fields recovered from the city’s rubble.

Moreover, Wright’s Broadacre City model avoids the hub-and-spoke conceit that was first popularized by Ebenezer Howard in the late 19th century and which became the model for American thinking about suburbia. Instead, Wright sees only urban cores and then a Jeffersonian countryside with small market towns like Richland Center, Wisconsin, where he was born, creating smaller moments of density in a continuous grid that is both rural and suburban.

We have indeed moved closer to such a vision by the way sprawl in the United States has organically developed. Suburbs have stretched so far into the countryside that the exurban areas are difficult to tell apart from rural areas. Up and down Wisconsin’s Fox River, for instance, 40-odd miles away from downtown Chicago, former industrial and farm-market towns have turned into cores for far-flung exurbanites, with coffee bars and fancy restaurants taking over the main streets and small apartment blocks filling in gaps as places to live for those who serve this new economy. The pattern is repeating itself all over the Midwest and was already the norm in the newer, multinodal cities of the West and Southeast, whether it be Los Angeles, Dallas–Fort Worth, or Phoenix.

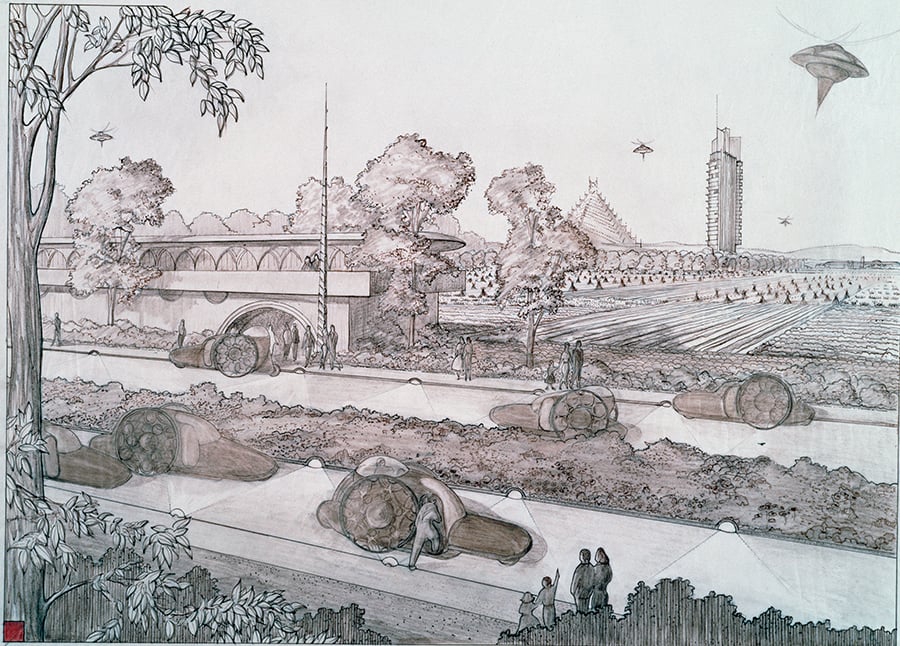

What Wright did not anticipate was that the accumulation of capital in cities would strengthen their cores as enclaves of power, even as they continued to sprawl. What he also did not foresee was that technology would not dissolve as quickly as he had hoped into the flying cars and other forms of automated transportation he added to his postwar versions of Broadacre City. Instead, we have seen the continual construction of more roads and warehouses, serving both the just-in-time inventories of producers and the equally time-pressed desires of far-flung consumers, which dominate so much of the exurban landscape. Now, the advent of driverless cars, drones, and other forms of more efficient transportation promises to fulfill that part of his vision.

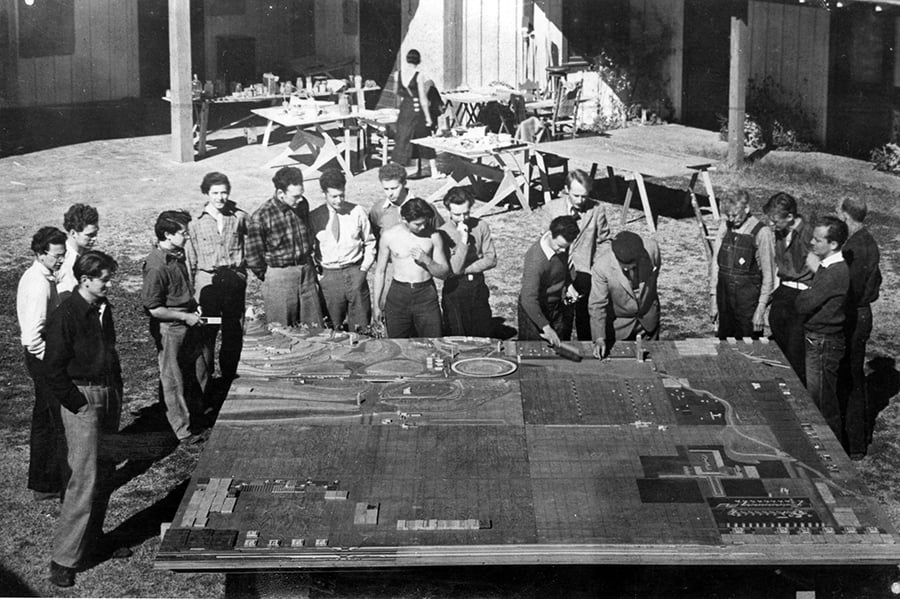

What Wright also got wrong was the strength of the nuclear family at the core of his vision. That is to a certain extent surprising, as for most of his adult life he led an existence that was far beyond such conventions. His homes, first in Oak Park and then in Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, were offices as well as homes and became, after the establishment in 1932 of the Taliesin Fellowship apprentice program, veritable communes where a diverse group of people worked, lived, and engaged in cultural pursuits together.

In that manner, Taliesin remains a model today for how to create communities in sprawl that are smaller versions of American campuses, from Yale and Princeton to numerous land-grant colleges in rural communities, which have long served as the ways in which we tested and formed communities beyond kinship or place, as well as modern versions of the monasteries that were once the agricultural and cultural centers on the edges of civilization.

Beyond the large scale of Broadacre City, Wright also proposed ways in which the basic unit of suburbia, the single-family home, could be both intensified and extended. His early homes are pinwheels rotating around central cores consisting of the hearth, which serves as both symbolic heart and the locus for the technology that provides the services inhabitants need, bringing the logic of the skyscraper, with its core and window walls, to the domestic realm. He then, in a series of projects that started with a “quadruple block plan” version of his Home in a Prairie Town (first described in The Ladies Home Journal in 1901), proceeded with the so-called Roberts Block of 1903–04 and then a decade later scaled up to a quarter of a section (a section being the square mile that is the basic unit of the Jeffersonian grid). In these designs, he showed how the asymmetric units of his homes could coalesce to fill out the city blocks of suburban Chicago, creating shared open spaces and a sense of community built of individual units. Unfortunately, he never had a chance to construct this bottom-up community; though he imagined Usonian developments and a romantic housing development in Los Angeles (Doheny Ranch, 1923), his commissions remained for individual buildings.

Today, young architects are picking up on these ideas while eschewing the forms that made these proposals appear alien to potential home dwellers, developers, and builders. They are learning from both the Oak Park subdivision and the various versions of Broadacre City, but they are also doing something just as important that is inherent in Wright’s theoretical projects and writings: They are offering alternatives, holding up mirrors to sprawl, and in general making us look at the built environment that spreads around us rather than just obsessing about walkable streets and parklets. These architects are also the first generation of designers to do what Wright did, namely to look at and design for sprawl.

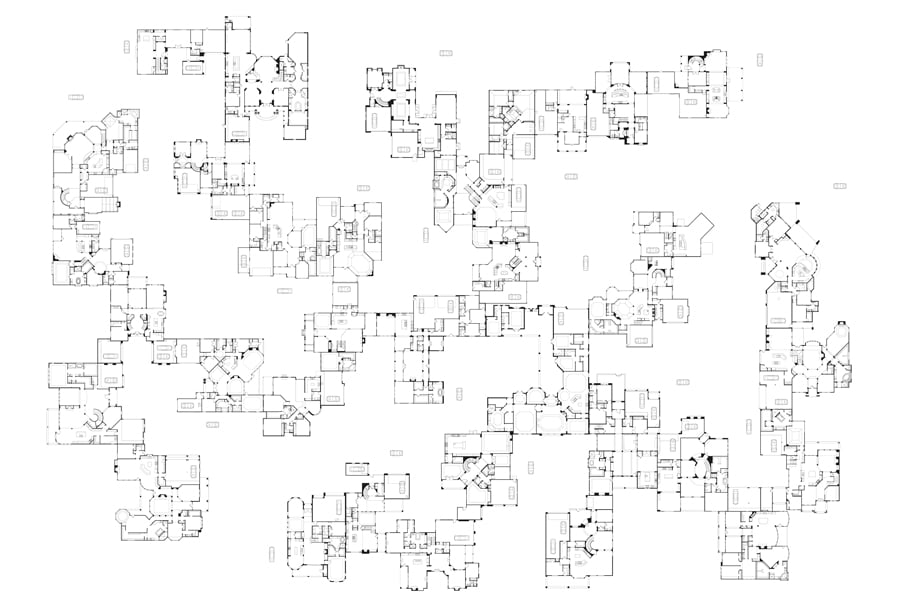

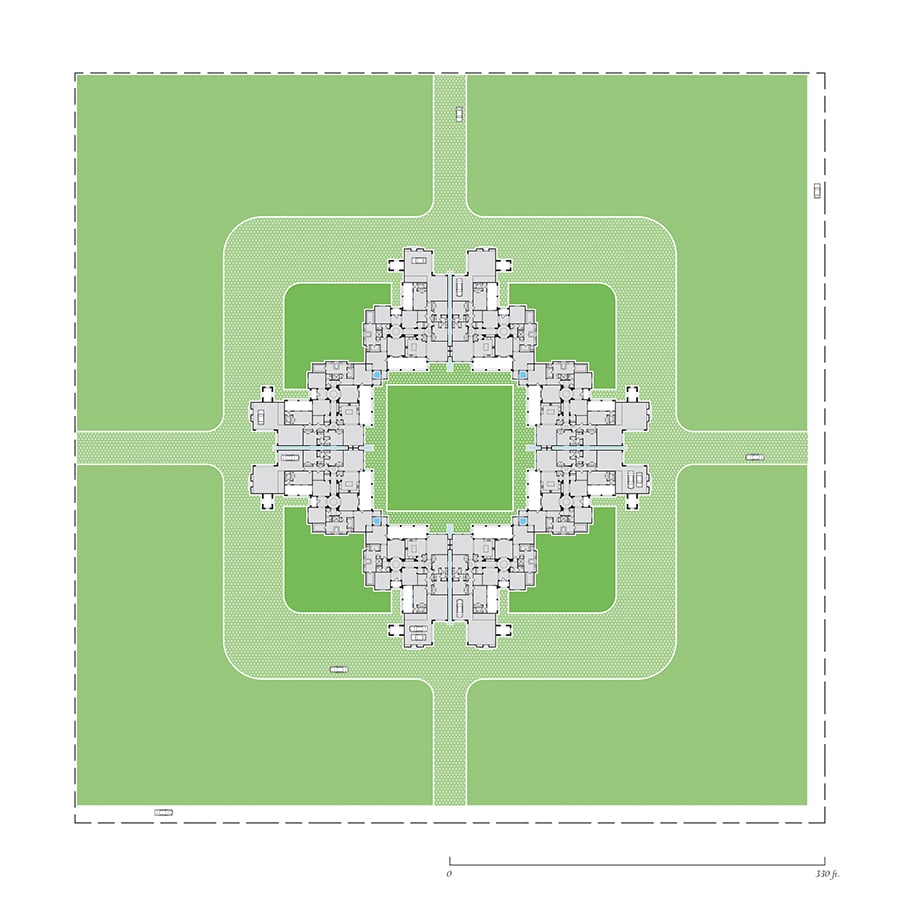

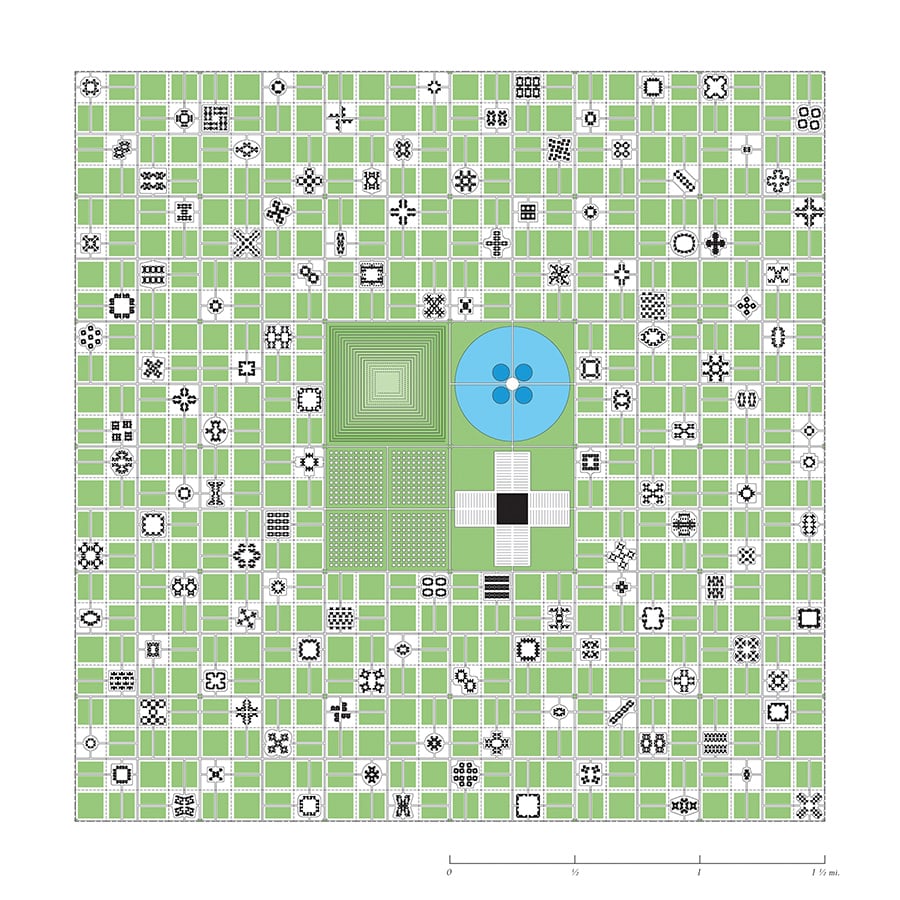

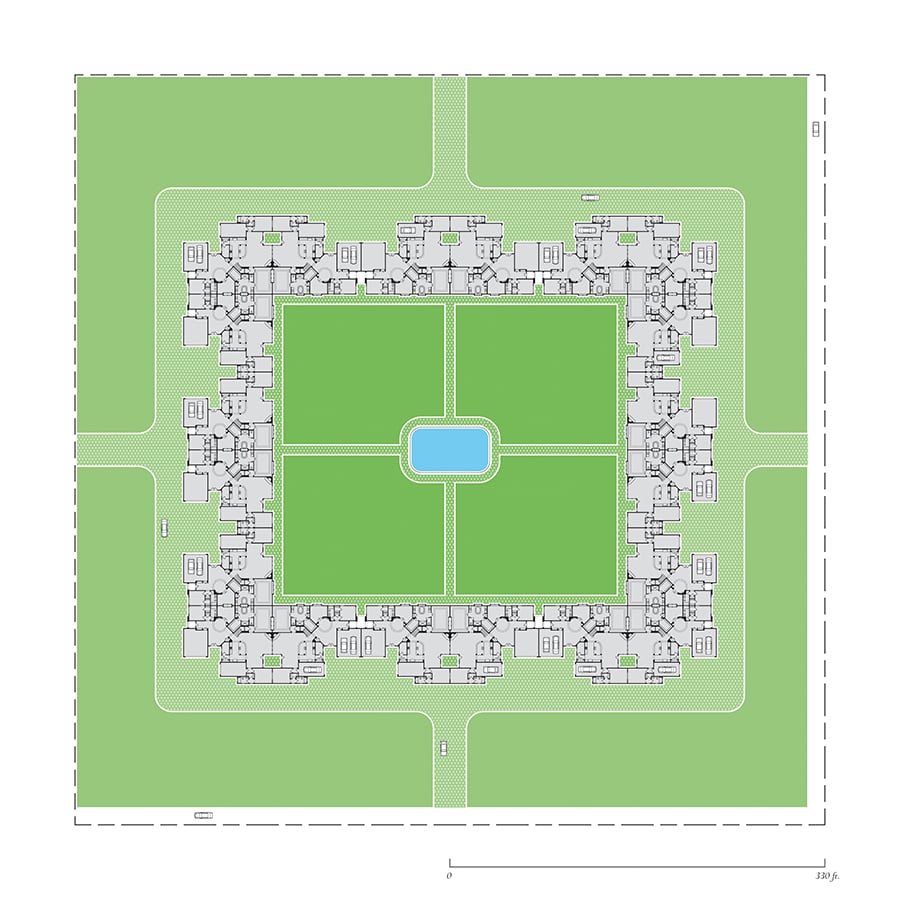

The most complete proposal I know is by Keith Krumwiede, an architect who now lives in New York City but who spent years in Texas and California. His Atlas of Another America (2016) proposes a Broadacre City–like division of suburban developments in the rural grid. In this case, however, Krumwiede has made an exhaustive research into the plans of existing suburban dwellings and has found ways to extend and combine their floor plans to create compounds surrounding shared open space. Though this densification and extension (there is much more open space in this suburban model than the cul-de-sac or plat development currently allows) might not be realistic—these are satirical compositions—the project’s vision is as compelling and as beautifully presented as that of Broadacre City. Like Wright, Krumwiede started with the grid and proposes an equal sprawl without an emphasis on central and subsidiary cores. Recalling Wright’s earlier Oak Park works, he starts from the basic suburban house and opens it up, connecting it to a larger community. He does so with current forms and conditions, and, in his proposal for his larger building blocks, even seems to be imagining the kind of collective community Wright built at Taliesin.

Similarly, the young architects Ashley Bigham and Erik Herrmann created Safety Not Guaranteed, in which they represent suburban homes in models that extend and warp into the fortresses that they have become. In this manner, they expose the fact that we cocoon ourselves in our homes, and show how we might confront our own paranoia and become more playful—in one case quite literally, as they let visitors play with the models in a sandbox. This is not a direct continuation of Wright’s work but a critical commentary on the myths he articulated with such power.

On an even more theoretical, but also visually more compelling, level, the artist Doug Aitken, whose videos are among the most haunting explorations of sprawl I know, constructed an installation, Mirage, for the Desert X art installation in California’s Coachella Valley that turns every surface of a suburban home into a mirror. The standard ranch house dematerializes and reflects and intensifies the gridded sprawl around its disappearing shape. The model is meant to travel throughout America mirroring and making us aware of sprawl the same way Broadacre City’s model did.

There are more concrete models for developing sprawl, but most still concentrate on creating transit-oriented developments or reducing the cost and wastage of suburban construction. A good example is a project by Matthew Salenger of coLAB Studio, the Vali Homes Prototype, which shows how we can make the basic home unit more sustainable and affordable. Starting with manufactured components that can be easily assembled, and assuming small footprints that emphasize the relationship between the houses’ interiors and both the landscape and the community, Salenger and others are picking up on the experiments Wright first made in Oak Park and imagining how they might work in today’s suburbs.

What all these projects lack, however, is a concrete analysis of the economic, physical, and historical definitions of sprawl, coupled with a proposal as to how we might be able to work within and beyond those definitions to create a suburban world that is more sustainable, connective, socially open, and just more beautiful. Frank Lloyd Wright set us all a challenge; it is up to us to design a better sprawl.

You may also enjoy “Frank Lloyd Wright Was a Proto-Algorithmic Architect.”