December 1, 2017

Istanbul Design Biennial Curator Jan Boelen Wants to Shake Up Design Education

The curator and teacher hopes to “stretch both the space and time” of traditional design schools.

Over the last six years, the Istanbul Design Biennial has emerged as an important center for critical thinking around design. The first edition in 2012 explored digital and DIY means of design and production with “Adhocracy;” the second edition tracked the shifting goalposts for design with “The Future is Not What it Used to Be;” and in 2016, it questioned design’s role in civilization with “Are We Human?” Next year’s edition, under the direction of design critic and teacher Jan Boelen, will take an educational approach with the theme “A School of Schools.”

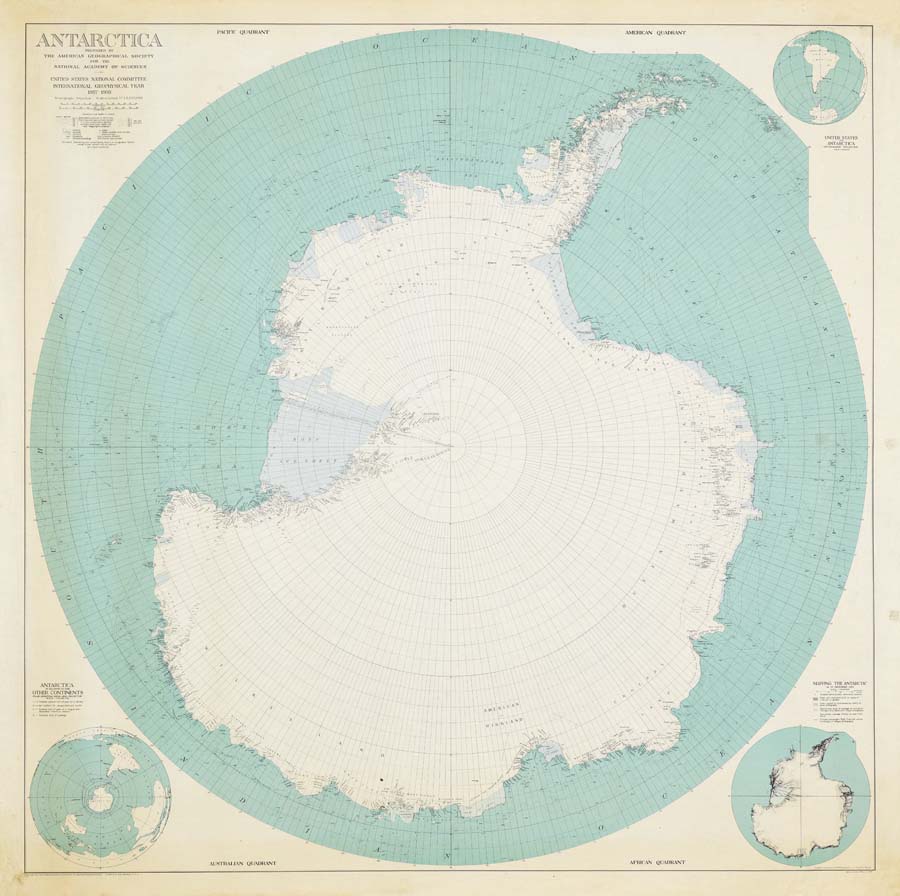

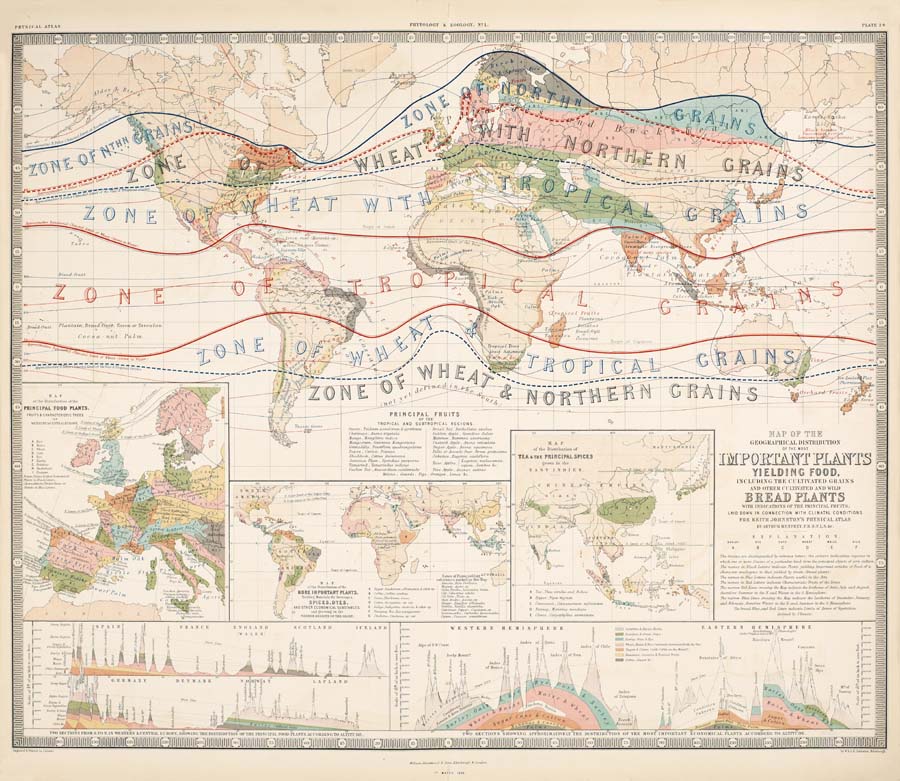

Boelen is the founder and artistic director of Z33 House for Contemporary Art in Belgium, artistic director of experimental laboratory Atelier LUMA in France, and head of the Social Design masters program at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. In Istanbul, he hopes to “stretch both the space and time of the traditional design event.” Rather than create exhibits, participants will run a variety of learning situations, or “schools,” under eight themes: Measures and Maps, Time and Attention, Mediterranean and Migration, Disasters and Earthquakes, Food and Customs, Patterns and Rhythm, Currency and Capital, and Parts and Pockets.

The Biennial has put out an open call for these schools, as well as one for “learners:” participants who can be from any walk of life, as long as they are interested in a year-long investigation of design.

Metropolis spoke with Boelen to understand the thinking behind the program, and what the international design community can hope to learn from “A School of Schools.”

Avinash Rajagopal: Can you explain the theme for the Istanbul Design Biennial, “A School of Schools”?

Jan Boelen: Yes. So, I always ask myself, is there a need to do a project like the Biennial? And if the Istanbul Design Biennial wants to take part in an international discussion, what could that be? The best thing that I could do, what I think is needed today in the design discourse, is to raise a discussion on design education as such. For me, that’s a very important topic, mainly because I see quite a lot of international students from different schools applying at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Ninety-nine years after the Bauhaus, schools are still letting their students present objects and products that are more of the same, and there are a lot of the same solutions that created the problems and the situation we are in. We have to rethink the systems that are around us and that means also rethinking education. That’s why I thought if there was any urgency today it was to address design education at large.

Biennials tend to be obsessed with professional practice. Is there a reason why Istanbul is particularly suitable for a Biennial focused on education?

Yes, of course. In Turkey, especially given the political situation, designers feel disconnected from the international discourse. In a school, or in this school of schools, you can bring different people together to build a new possible future. So, that is certainly one of the urgencies I found in Istanbul itself.

The Istanbul Design Biennial is an initiative of IKSV, the same organization that is also setting up the art biennial, theater festival, film festival. So it’s this cultural institution that instigates the biennial, which is fundamentally different from all the other design events, where most of the events are commercial or have other starting points, you could say.

You were involved with BIO 50, which was a great example of an event centered not around exhibitions, but around team building and workshops. We definitely see some of that in your proposal for Istanbul. Why did you want people to come together as part of an activity rather than as part of an exhibition?

For me, designing is an active mode. It’s dynamic, it’s a process, rather than just a product. And so I think prototyping, testing, trial and error are very interesting tools to set up discussions around certain topics. So what we want to do is to create eight very ambiguous themes. It’s not a super managed process, but more something that evolves.

In addition to inviting people to create workshops, lectures, and other situations of learning, you have an open call for learners.

I’m looking for people who want to participate and exchange knowledge, and we will match the learners with the schools. We want to bring a variety of people together: not only in terms of local and international, but also in terms of professional backgrounds. Not only designers that are working with other designers, but programmers, coders, engineers, sociologists, art historians, critics working together around projects with people from different generations, different genders. Ambiguity, uncertainty, and variety are the key elements to make something into a successful collaboration.

Does your experience at the head of the Social Design program at DAE play into this?

I don’t really believe in social design as such. I believe in design where several aspects, like from technology to economical aspects to cultural, social, environmental issues are integrated and are taken care of. But they fit to the design question or the need that was formulated in the beginning. I see too much the lack of thinking around why something was made. The “why was it done?” is forgotten. Especially in a world where the technological and the economical logic have kind of self-fulfilling power—as the architect Cedric Price said, “If technology is the answer, what was the question again?” You can also ask: “If profit is the answer, what was the question again? “

The school is a very interesting place where the market—as if there is a market, by the way—and these kinds of elements don’t have to play a role directly, but can be connected, as in a laboratory. That also fits into the cultural environment that the Biennial is.

What do you think designers or design educators can hope to learn from this exercise?

What I want to discover is, what kind of skills can we learn? How can we learn a certain attitude to deal with reality? Design has the enormous potential to create products that deal with our reality. This productive mode is necessary—to construct and make your own reality rather than becoming a consumer and a slave of reality. But if we are still dreaming of a reality that we can construct ourselves, then what are the skills that we need to know and to be in control of?

You may also like Disegno Ergo Sum: Istanbul Biennial Conflates Anthropology with Design