August 10, 2023

Lendager Completes the World’s First Ecolabeled Kindergarten

Left empty for ten years, the abandoned institute—consisting of a brick building from the 1930s and a concrete building from the 1960s—donated 12,000 roof tiles, 61,500 bricks, and 2,600 pieces of sheet metal cladding to the plan of a differentiated building designed to the scale of children.

“We have rewritten the ‘form follows function’ tradition to a ‘form follows availability’ process,” says Anders Bang Kiertzner, Lendager’s director of circular advising. Asking the existing building what it can become is the crucial question, Kiertzner says. The result is a 16,000-square-feet new building that impresses architecturally, winning the 2022 Danish Design Award in the Save Resources category. While it occupies an integrated area on the inside on a U-shaped floor plan, eleven building blocks are lined up on the outside, some with asymmetrical gabled roof structures and each with different facade cladding.

The buildings’ alternating roof and wall coverings are made of the school’s bricks, roof tiles, and corrugated sheet steel. Inside, the floor of the orangery—the central, unheated glass house through which the children enter the building—is also covered with the bricks from the former school. In addition, 6,000 tons of demolition concrete were crushed and used as a leveling layer under the kindergarten and as aggregate for the foundation and floor slabs.

Dismantling the school and managing the materials was essential to the architects’ process—the office was responsible for the material mapping while the commissioned demolition contractor was liable for the cleaning and preparation of the materials. And when Lendager conducts material screenings, the team looks for more than functional, structural components they can build with. “We also have a subcategory of materials that serve as identity markers,” Kiertzner says, adding that the architects transformed the school’s observatory dome into a playhouse.

A big clock from the school yard has been placed in the orangery and serves as another “identity marker” that may be familiar to parents who attended the former school. “That, of course, gives the project anchoring in the community,” Kiertzner says. Dealing with the complexity of the circular building, Lendager developed specific guidelines as part of The Swan’s tender process, paving the way for selective demolition and upcycling materials.

“Following legislation, we had to send the tender for demolishing to at least three bidders,” says Niklas Nolsøe, design director at Lendager. He explains the Danish public tender process, adding that these tenders typically just ask for sustainable knocking down without specific guidelines. He adds, “By giving the providers the same methodology of how we want the product to be taken down or at what state we need it to be stored, all three demolishers had to price the exact same thing.”

To avoid getting taxed with a CO2 transportation fee for shipping materials over a certain distance, Lendager concentrated on collaborating with firms that could set up their operation on the construction site. “Not only did we have to co-design the dismantling, sorting, remanufacturing, and reprocessing process, we also had to orchestrate how and in which sequence this is going to be done by different actors on the actual construction site,” Kiertzner says.

Whenever design director Nolsøe faces the question whether circular building is scalable, he responds with a counter question: “Can we afford it not to be?”

“This is a new era of architecture—the expression, the language, the ways of using resources,” Nolsøe concludes. “The ‘form follows availability’ [approach] requires more of us architects, but it also gives a lot more design and freedom back.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

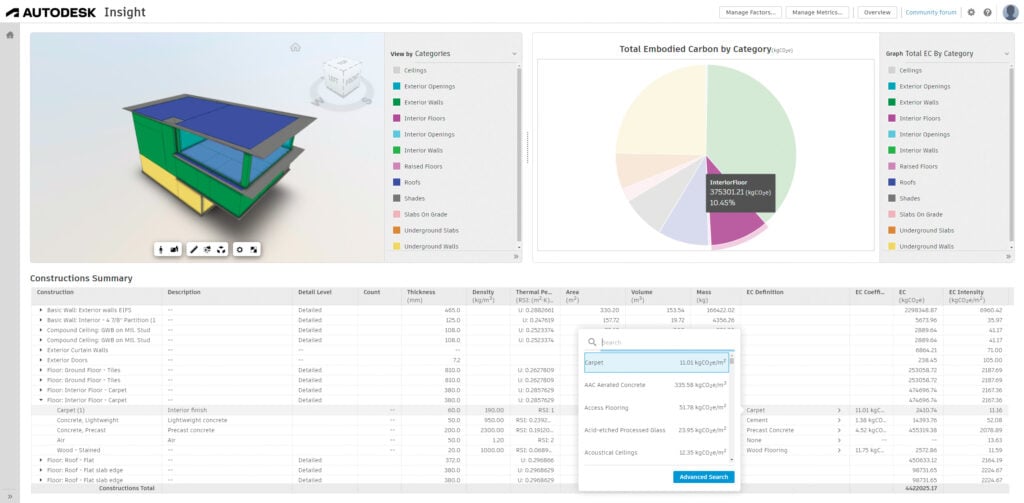

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.