September 13, 2022

A New Book Illustrates the Past Half-Century’s Various “Offices of the Future”

The Office of Good Intentions. Human(s) Work by Florian Idenburg and LeeAnn Suen. October 2022, Taschen, 592 pages, $60

Together, the book takes a wide-ranging look at how the emergence of digital technology in the mid-twentieth century allowed architects, designers, charismatic CEOs, and major corporations to dream up new and unusual surroundings for information workers to process information. As digital technologies evolved—from punch cards to cloud computing—they have enabled white collar work to take place anywhere and everywhere.

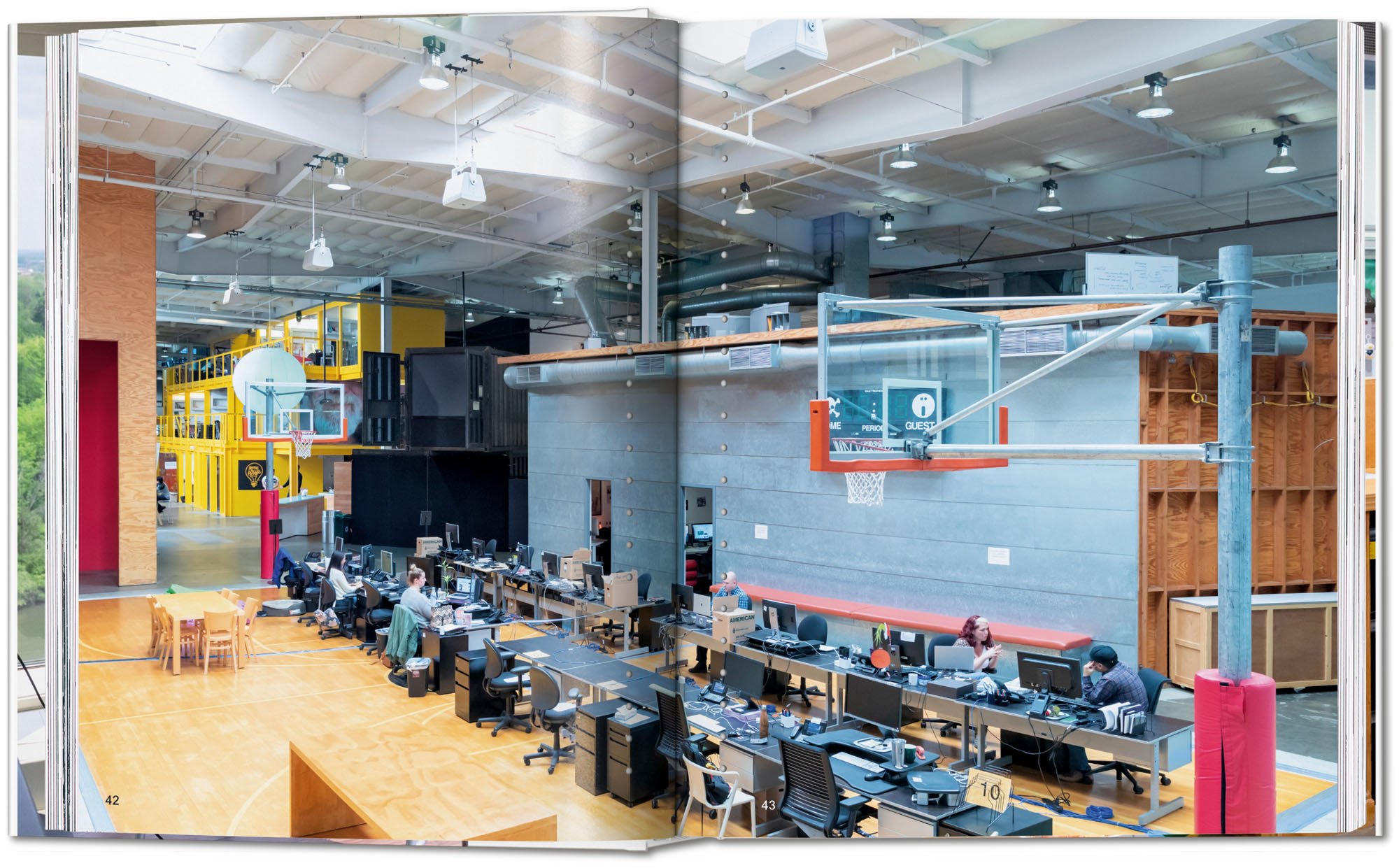

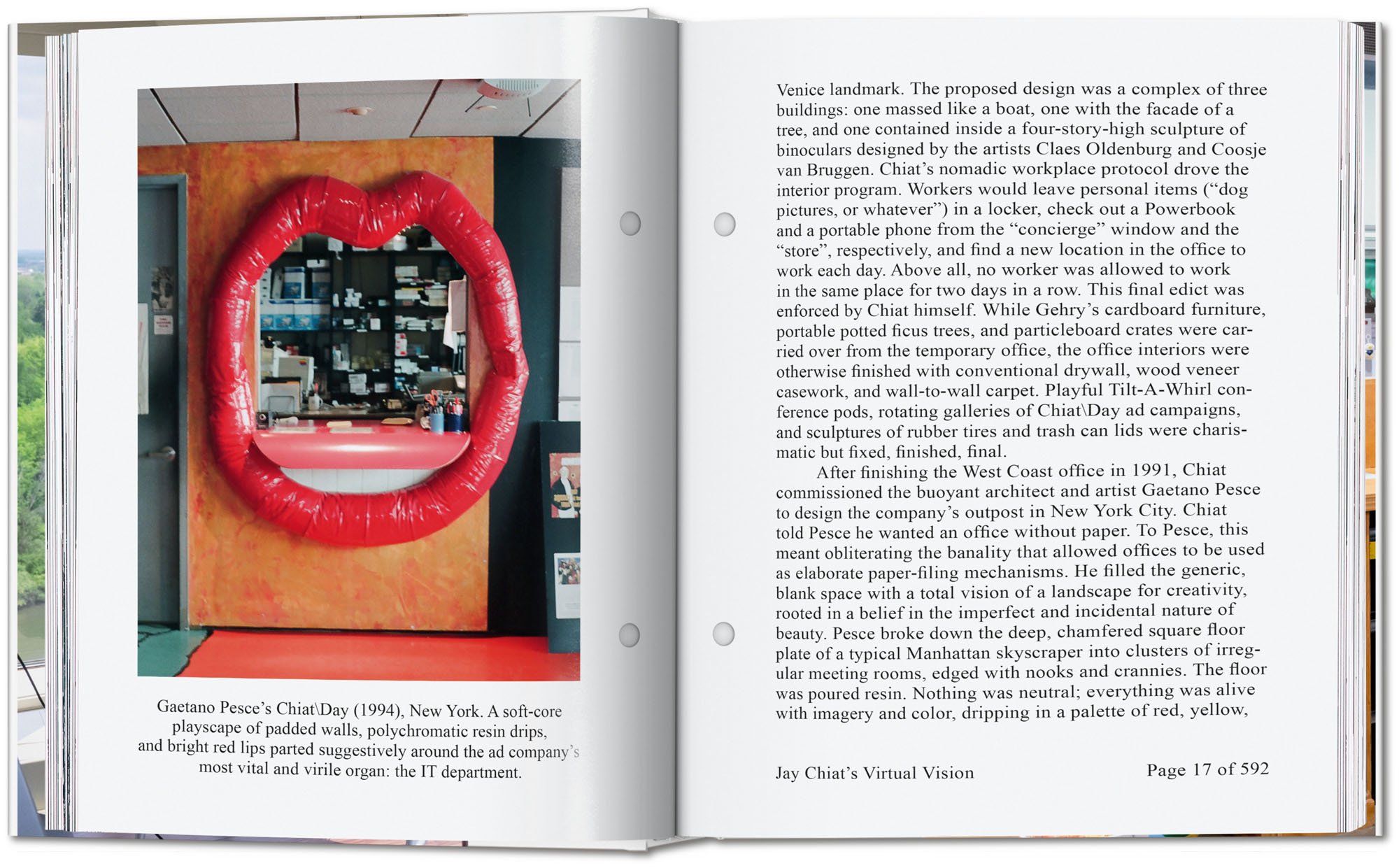

But since we can now work anywhere, how and where we work has taken on new significance. To explore this, Idenburg and Suen take a look at the quasi-religious overtures of projects such as Arcosanti, companies such as Steve Jobs’ Apple, and initiatives such as the bring-your-dog-to-work-day-every-day zeal of Clive Wilkinson Architects’ Los Angeles office for advertising firm TBWA/Chiat/Day. The architects unpack experiments in generating “water-cooler magic” at WeWork and the hacker-houses that inspired it, and they trace the wellness-focus of many contemporary offices to the garden-like interior of Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo’s annex to the John Deere World Headquarters in Moline, Illinois, and their verdant courtyard for the Ford Foundation building in New York City. They discover co-working experiments in homeless encampments near LinkNYC Kiosks and contemplate the bedrooms of social media stars and video game streamers.

Those looking for a neat historical arc that traces the history of the workplace from early paper-pushers to the mid-century corporate castles, through the dot-com lofts, the Googleplexes, the Wings, the WeWorks, to the ad-hoc solutions of COVID-19, may be disappointed. So, too, will anyone who is looking for a pre-packaged solution to the workplace’s present identity crisis. Instead, the authors offer something more interesting: A discursive exploration of the many disjointed ways designers, architects, executives, technologists, and gurus have sought to make work something more than just work.

Some of the examples are successes, some are failures, and some failed in their own time but today seem prescient. Others are deeply dystopian. As the design industry, and indeed the whole information-working world, navigates our present moment of uncertainty, we would do well to look at the past half-century of experiments in re-skinning the office. How else, as the authors ask in the introduction, “can architects evaluate the political and ethical positions that are required when producing spaces that seek to disguise work as leisure, community, self-care, and social life?”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

These Biobased Products Point to a Regenerative Future

Discover seven products that represent a new wave of bio-derived offerings for interior design and architecture.

Viewpoints

ThinkLab Shares Insights on the Dynamics of Sustainability in Decision-Making

ThinkLab helps us understand how the realities of product selection can maximize designers’ influence and impact.

Profiles

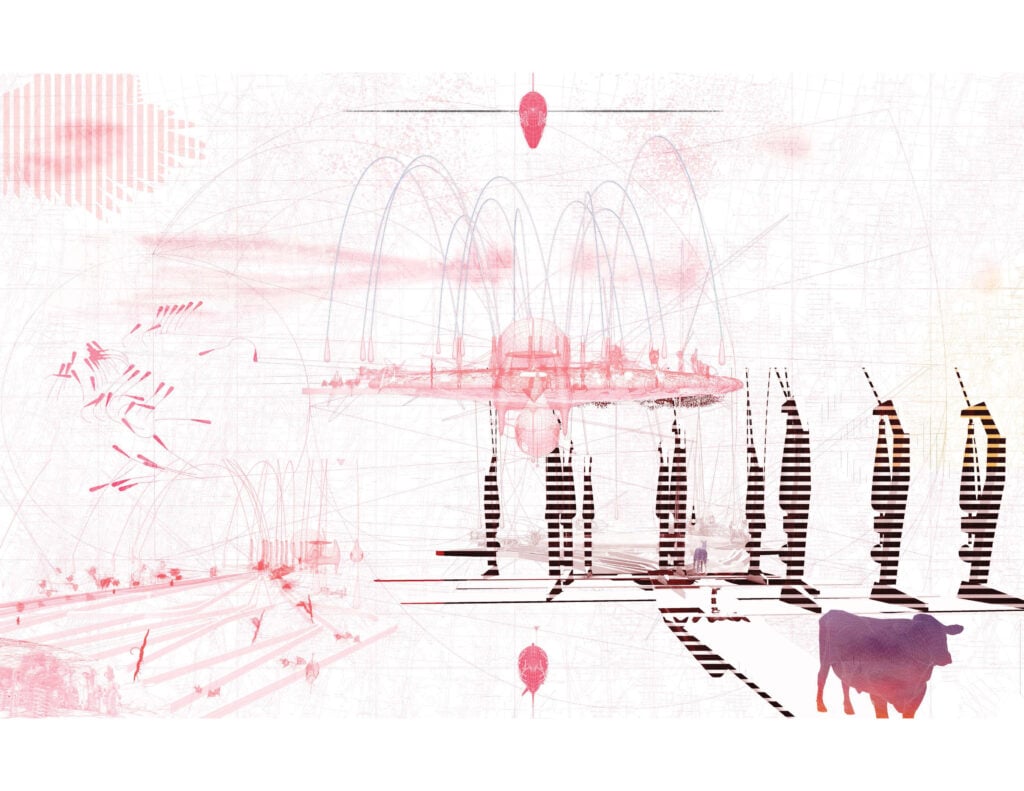

Students Imagine New Ways to Deepen Our Connection to Our Environment

Students from University of Pennsylvania, University of Michigan and Imagine New Ways to Deepen Our Connection to Our Environment