July 20, 2022

An Exhibition Explores the Complex Legacy of America’s Most Common Construction System.

Ad-hoc and idiot-proof, the technique engendered madcap possibilities of speed and expansion.

The question is especially relevant to American Framing, an ongoing exhibition at Chicago’s Tadao Ando–designed Wrightwood 659 gallery that celebrates the facts and potentials of softwood lumber construction. Inside the Wrightwood’s main hall, pruned Chicago brick joins with Ando’s signature svelte concrete to create a rarified setting for art and, on occasion, architectural exhibitions. Both disciplines fall within Paul Andersen and Paul Preissner’s curatorial frame, though to what species the multistory distressed wood cage they have wedged into the atrium belongs is anyone’s guess. The installation—a tribute to the mass-repeated figurations of developer housing—rises to a curious denouement: Rather than resolve themselves in a gable or common roof, its studs and rafters nosedive toward the floor. A bag’s worth of nails and the framer’s savoir-faire are all that prevent a clattering crash.

It would seem an irresistible metaphor given the subject matter, but Andersen and Preissner, who are otherwise inclined to ironic disavowal, mostly maintain a sanguine outlook. When not running their independent design practices, the two teach at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) and collaborate on exhibition projects. As Andersen recounted at the May opening, he and Preissner were each at work on a house when they “stepped back and noticed how beautiful wood construction was.” This mutual affection was the starting point for the American Pavilion at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale, from which the Wrightwood show, and a concurrent edition in Prague, is adapted.

In Chicago, however, American Framing finds its natural perch. From the balloon frame sprang forth a city. Forests in the Upper Midwest were logged and the trees transported to Chicago lumber yards for processing. Softwood lumber quickly found its way into the local building supply. It’s uncertain who hammered out the schema, but inventor Augustine Taylor was the first to implement it. In 1833, a plucky crew acting under his direction built a modest Catholic church, St. Mary’s, in an area that would become the Loop. It was rumored that veteran carpenters watched on with a mixture of amusement and derision; in retrospect, the feeling may have been something closer to dread. By the 1860s, one Chicago enterprise was selling prefabricated balloon frames for export out west. Ad-hoc and idiot-proof, the technique engendered madcap possibilities of speed and expansion.

It might be said that industrialization reached architecture before the 20th century, coincidentally, at the behest of a different Taylor—Frederick, known as the father of American mass manufacturing. The enormous success of “Chicago construction” may have been directly responsible for the city’s devastating 1871 inferno, but its spare, efficient tectonic also offered a template for the steel framing that overtook it. Steel cages plus the elevator yielded the skyscraper, whose wanton profligacy contributed to an urban crisis that caused social critics like Lewis Mumford to despair about the direction modern development was heading. Meanwhile, far from the country’s swelling cities, the balloon frame made itself indispensable to the settling of cleared Indigenous lands. Its successor technology, platform framing, which introduced horizontal levels at intervals as an economic (shorter units of lumber) and safety measure (fire retardance), would be vital to the cause of postwar sprawl.

Aspects of this summary make their way into American Framing, but there are noticeable lapses. In the upstairs gallery, spindly basswood maquettes illustrate the panoply of forms achievable through light framing. There is a model of St. Mary’s Church and another of an ingenious round barn, built in 1905 in rural Illinois, but without supplementary descriptions to lean on, they oscillate between structural diagram and cartoon. For a moment, the inclusion of “Spike’s Doghouse, Tom and Jerry, 1952” appears a telling admission on the part of the curators; indeed, there is something childlike in both the presentation and the insistence on preserving the unfinished in all its apparent honesty. Then noticing the exhibition’s relative sparseness, and the prominence accorded to the models (exactingly crafted by UIC students), one can’t help thinking that the weight Andersen and Preissner vest in popsicle sticks is here misplaced.

Stick framing’s social ramifications are made more palpable by Chris Strong’s photographs, which line the walls of a rear gallery and the corridor leading to it. Strong portrays the laborers who put up America’s ticky-tacky homes, from every bumptious McMansion and godless demi-Versailles to all those five-over-one eyesores. He catches framers nimbly navigating thickets of rafters and also at rest; in one memorable image, taken on a snowy morning, a group idles in a Home Depot parking lot waiting to be drafted for a day’s work. Both evocative and precise, the pictures are imbued with a humanity that evades the show at large.

Daniel Shea’s complementary photographs takes this evasion as a point of departure. Ranging from bleary-eyed and blissful portraits of plant life to construction-site abstractions, the monochromatic images implicate the natural in the artificial and vice-versa. According to the project statement, the pictures also attempt to “destabilize expectations about American culture through meditations on its origin myths.” It’s a commendable aim that Shea, who, like Strong, is a UIC graduate, pursues with studied intensity. If only the overall effect weren’t so turbid or heady, conceptual obliquity not being among American Framing’s strengths.

The exhibition fares better when it telegraphs the connections it seeks to set up. Andersen and Preissner put great store in what they call “the ordinary,” which, unlike contending terms that might trigger associations with older, staler discourses (e.g., “vernacular”), resonates across multiple registers. For example, in eloquently depicting mundane expressions of precarious labor, Strong’s photographs make it possible to better comprehend precarity as the wider social problem it is. With their (untitled) installation, Andersen and Preissner recuperate everyday signifiers and direct them toward novel design ends. These are the gable, hip roof, and other commonplace suburban forms either taken for granted by the wider culture or beneath the contempt of architects. In the lofty gallery context, this strategy of estrangement is the norm, but as Kate Wagner has tirelessly catalogued on her blog, McMansion Hell, developers in the real world often get up to far weirder high jinks.

Unsurprisingly, a bit of nationalist eye-poking creeps into American Framing. In Venice, Andersen and Preissner superimposed a wood-frame structure across the front of the American Pavilion to obscure the structure’s prim Palladian features. The illusory inhabitation was tall, wide, and not very deep, nearly all roof, with elevated platforms to carry visitors and notional dormers blown up to the size of portals. That Andersen and Preissner were forced to engineer the thing within an inch (nay, centimeter) of its life accentuated the almost farcical degree to which the provisional technique and Midwestern pragmatism are bonded. Evidently, Venetian carpenters were bewildered by a method of construction two centuries old, while their counterparts in Prague, where another abbreviated structure was erected, had to be led along by a framer who had improbably spent years employed in the Atlanta trades. But even at the Wrightwood, installers didn’t take the architects’ word. Wary of its load-bearing capacity, they went ahead and reinforced the multistory assemblage with metal stripping. Viewed from the top-floor mezzanine, the stripping haphazardly bundles the timbers like tape on a hastily wrapped present.

A closer engagement with framing’s history would have been warranted, and not simply as a mode of redress. Giedion, who was the first historian to elevate the balloon frame to the level of serious inquiry, and whom Andersen and Preissner closely follow, analogized its principles of efficiency to the design of the Windsor Chair. Though deriving from England, the chair was granted special “artistic consideration” in America, he wrote. Weirder material-cultural “interrelations” undoubtedly exist—many are likely bound for the imminent, all-inclusive catalogue—but Andersen and Preissner might have pursued them more energetically in the gallery format.

Peering into wood framing’s origins reveals imbricated legacies. For instance, rather than an arcane barb lobbed by craftsmen-skeptics, “balloon frame” (so light it could blow away) was a botched transliteration of maison en boulin, a stick-framing technique used in French Missouri whose antecedents were probably the poteaux en terre and poteaux en sole of French Louisiana. Points of overlap could have been drawn and inferences made about the balloon frame’s purported Americanness. By contrast, the curators could have chosen to problematize their premise by reaching into the recent past—the 2008 economic crash, which made millions victims of the American dream. What bearing did 2x4s have on sub-prime mortgages? Does 2x-construction uniquely structure contemporary American desires as the show implies? By focusing so intently on the skeleton, American Framing only partially apprehends the entangled set of phenomena it staggers into.

But the organizers’ critical attitude lies with architectural desires. Wood framing is characterized by “a lack of disciplinary prestige,” reads the terse introductory wall text. Architects, acting in accordance with a code of “prejudices and habits,” have remained immune to its charms. Needless to say, this is an overgeneralization. Already in his 1941 account, Giedion called to mind Richard Neutra’s use of dimensional lumber in his residential designs. Far lesser authorities need be consulted to establish Frank Gehry’s credentials on this score. Then there are those of Andersen and Preissner’s peers who are working in the same, if not adjacent, lane, including Jennifer Bonner and Andrew Holder of the Los Angeles Design Group. (Both have a base at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, which perhaps rendered them ineligible in this all-UIC production.) All tease out the formal implications of particle board, CLT, and other mundane materials, while promising greater areas of application—in the best instance, mass housing.

Andersen and Preissner distinguish themselves by what they impute to wood framing, namely, a baggy populism. As Andersen told Metropolis in 2019, “No amount of money can buy you a better two-by-four than the one that’s also in the crappiest house in town.” This may strike some as a provocation, but it is, in fact, a balm: Whatever the problems that pock-mark our no-longer supple republic (it’s now older than many European states and geriatric compared with postcolonial nations), we can take solace knowing that, on a basic level, we’re all equal before the market. We walk down the Lumber & Composites aisle at Home Depot, if not arm in arm, then exchanging gruff nods of recognition. To expose this ideological error for what it is would require us to step out from this frame.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Ifeoma Ebo Is on a Quest for Urban Healing

Through trauma-informed design processes, Ebo aims for community stewardship and empowerment.

Products

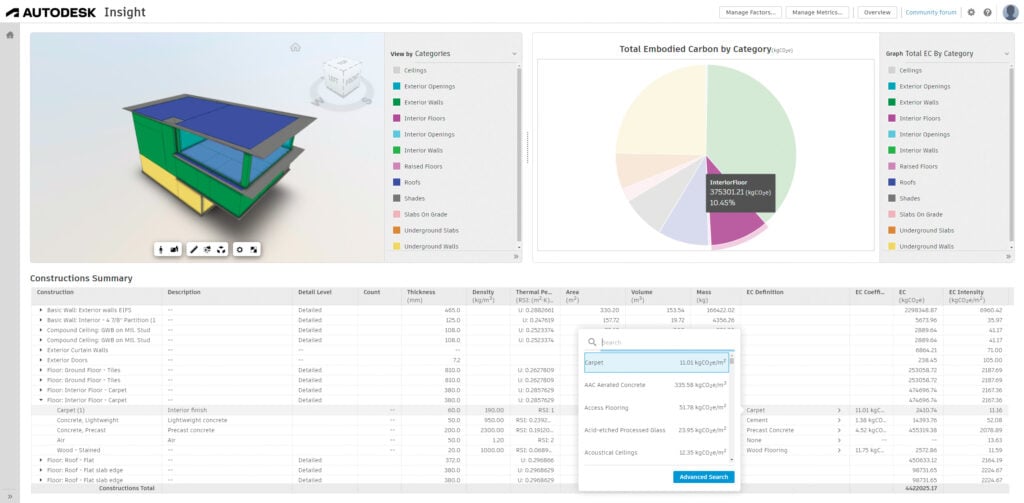

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.