October 12, 2022

Can Local Architecture Help Cure the Ills of Globalism?

This is how communities are built—through the generation and evolution of ideas about a place over time.

Li Wen

Architecture, being an embodiment of the socio-economic systems of its production, followed suit: Just as labor was shipped offshore, so was “progressive” architecture, serving as a propaganda tool for the global “arrival” of an emerging economy—e.g., China, UAE, etc. The starchitect arose during this period as a prime delivery system; their architectural spectacles juicing their surrounding economies to become destinations.

The economic momentum and market integration produced by globalism also seeded another form of global architecture. Boutique hotels, lifestyle centers, entertainment attractions, duty free-filled airports, luxury housing, and corporate business centers constitute a kind of homogenized design that I call the supporting cast. This category has rendered similar many global cities and tourist outposts, the hubs in the network of our present-day exchange. This homogenizing condition seems like the second coming of the midcentury International Style, only now with a far wider means of deployment due to globalism’s physical and digital infrastructure. So now the cultural impetus of globalism to learn and overcome our differences has been supplanted by simply less difference.

And yet, this global sameness has reinforced our desire to celebrate our differences. We continue to commune with local cultures and landscapes as a respite from the often inauthentic, placeless forms of globalism. In response, we need to re-frame “global architecture” as “trans-national,” where the distinct nature of various cultures is maintained through preservation, reuse, and newly constructed local architecture—one that interprets and expresses a place-specific culture without resorting to sentimentality, while also charting its vision for the future. In a trans-national condition, what defines “global” is not similar new architecture across regions, but the opposite.

Re-Engaging with The Physical Environment

In his seminal 1983 essay Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance, architectural scholar Kenneth Frampton outlined the architectural predicament of the “universalism” that was emerging in the 80’s, which has evolved into our present-day globalism. To counter that phenomenon, Frampton proposed the idea of the “Resistance of the Place-Form,” emphasizing the importance of local boundaries in place-making—not as the proverbial wall, but as a threshold where, in his quote of Heidegger, “presencing” begins. He lays out the architectural mechanisms to establish critical regionalism: topography, context, climate, light, tectonic form, and the argument of tactile over visual. All of these elements pertain to our response to the neutral tabula rasa approach of much of today’s global architecture, where advanced resources allow us to build anywhere, producing buildings that could be anywhere. To avoid sliding into such placelessness (or, on the flip side, local sentimentality), local architecture needs to focus on how we build. This should be embedded in its expression and experience, endowing it with a unique physicality not captured in today’s flat, virtual world, where globalism’s influence reigns supreme.

Since Towards a Critical Regionalism, architecture’s increased demands and technological advances have further hindered the making of locally relevant buildings and places. In response, those within and outside the profession need to push to shift the global dynamic toward a local one. How can this be done? For one, despite unfavorable life-safety codes, a litigious environment, and higher demand for comfort, we must push to implement strategies for natural ventilation and lighting, allowing us haptic engagement with our natural surroundings, particularly in taller buildings. Another step: instead of hiding building structures behind cladding, waterproofing, and fireproofing (a reasonable response to escalating operational costs and building performance and regulation dictates), we should celebrate them, expressing the local both in technique and material. My experience working with tech firms, which drive much of the present economy, found that they prefer reinforced concrete structures for their raw character, thereby reducing the need to clad and obscure. Equally significant is the rise of CLT as a primary structural material. When locally sourced, it can also integrate local economies while shortening supply chains to reduce embodied energy and carbon footprint. The alliance between the forestry industry and local government in Oregon to increase the use of heavy timber and CLT, even in high rises, is an example of public and private entities working together toward such objectives.

In Philip Ursprung’s book Natural History, Herzog & de Meuron remind us that “…if the medium of architecture is to survive,” the one-on-one experience “is the first priority, and the only way architecture can compete with other media.” In other words, instead of engaging in the virtual arena, where tactility is mute, we need to push in the realm of reality. One can experience the power of the tactile in Steven Holl’s Chapel of St. Ignatius, where the artisan bronze door pulls immediately feel upon touch that one is entering a specific—and important—place. But while hand-crafted items, from doors to fixtures, lend a unique tactility, they can also benefit from the facile customization that technology provides, evolving the artisan’s role through the making of local architecture. The stacked concrete structure at C-3 in Culver City by Gensler serves as an armature for the design collaboration between architect and fabricator (our profession’s modern day artisan); its custom reception desk, colorful stairs, entry portals, and interconnecting bridges are all areas of intimate contact. They lend this creative office building a casual and playful spirit aligned with the midcentury design legacy and contemporary lifestyle that shape the culture of Los Angeles. Such custom items do not constitute a local architecture in themselves, but when aligned with the building’s vision they act at a tactile level to express that one is “here,” not somewhere else.

Size and Place Matter

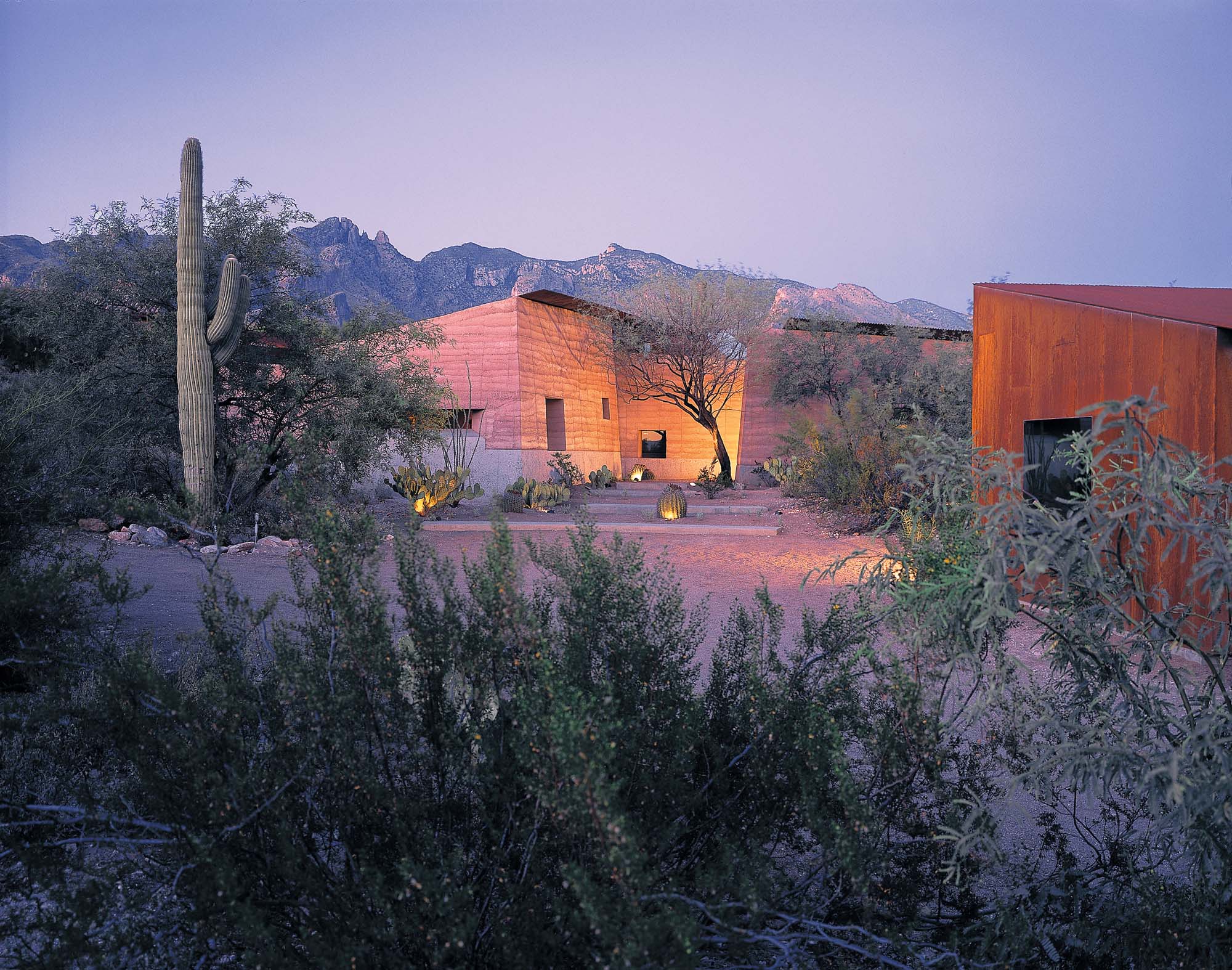

Much of what constitutes local architecture in America today tends to be at a smaller scale, where there is more latitude in regulatory constraints. The houses of Rick Joy in the American Southwest demonstrate the push noted above with their rammed-earth walls establishing the place-form mated with evaporative cooling ponds to respond to the local environment. At Joy’s Bayhouse in Connecticut, by contrast, the roof’s scale and pitch dominate the overall form and directly address the seasonal rain and snowfall of the Northeast. Joy adapts his modern design approach to each locale as opposed to replicating a formal vocabulary. This adaption of advanced methodology to context and culture is critical to the making of local architecture, charting a design trajectory for the future of the locale. This is how communities are built—through the generation and evolution of ideas about a place over time.

In scaling up to larger buildings, I’ve learned that with new construction (especially in America) beyond the size of about 100,000 square feet, mass production processes and economies of scale take over, leading to the culture of the typical, where design and construction fall prey to a collection of typical details that can easily stem from industry standards. The ability to respond at the scale of the human body is overtaken by the practical imperatives of building large. Most global architecture is bigger than we’ve ever built before, creating a condition where there is no precedent for a “local” context. But one strong counter argument is New York’s Rockefeller Center. From its planning, which adapts and scales down the Manhattan grid, to the tactility of its crafted brass doors and turnstiles, much of its architecture is intimately tied to its locale and to the human body. Similarly, the planning and massing of Morphosis’ Madrid Housing, a 141-unit public housing project completed in 2006, reflects a scale breakdown related to local typology, environment, and culture; specifically the area’s Moorish legacy of shaded courtyards and vent chimney stacks. The challenge of bigness to local architecture exists, but is not insurmountable.

The same challenges of bigness to local architectural production can be applied to global architecture practices. Attempting to re-position such large entities as “trans-national” practices is akin to modifying a car engine while it’s running. But as any mechanic will say, diagnosing what still works is the first step. For one, these practices have an established global footprint that is an effective delivery system for local architecture. And some global practices, like the one I came from (Gensler), have assembled a trans-national assortment of designers supported by a platform of global resources. Global design practices need to recognize and act on the premise that they are in a better position to push their clients—who are often complex financial conglomerates rendered simple and ubiquitous through branding—to veer from their homogenizing approach. Through the empirical knowledge of their local branches, such firms are better informed on how to architecturally adapt a brand to a locale to optimize business. While veering away from the culture of the typical was once considered an expense, it can now be presented as a business investment. The increased emphasis on ethnic identity worldwide makes this trans-national approach a growing imperative for global clients.

Balance

The ebbs and flows of human history chart a trajectory of an increasingly interconnected world. We are not entering an age of post-global architecture. But we can try to correct global architecture’s imbalances. My experience leading projects at Gensler’s Los Angeles’ office indicated that this is possible, at least at a regional scale. I was fortunate to have some clients who understood the differences between the locale’s ocean, desert, and urban landscapes, and the varying cultures and lifestyles that accompany each; encouraging our teams to design to those contexts. I learned to move quickly past the transactional parts of the client relationship to try to understand personal aspirations. Most clients have them, and one must seek those openings to gain the trust necessary to push. Though constraints always existed, we focused on trying to craft a vision for each project with the client, and in doing so, carve out space to design local architecture.

We are all now acutely aware of the perils of globalism: supply chain crises, expanding carbon footprints, numbing sameness, and deep inequality all run counter to its original promises of shared culture and mutual prosperity, sparking environmental degradation as well as an increase in resentment and identity politics. While it’s not a panacea, local architecture can help heal these problems in myriad ways, from catalyzing economies and shortening supply chains via local material and labor sourcing to strengthening identity and purpose by bolstering local presence and culture. And if one believes environments influence behavior, there are indications of hope. The media, which just a few years ago focused on the work of a global cabal of architects, each rising to prominence through a singular design aesthetic, are now highlighting remarkably diverse, locally-inspired designs from around the world. And if awards are any indication, there appears to be a growing trans-national consciousness within the profession—the presenting of the Pritzker Prize to Lacaton & Vassal and Frances Keré over the last two years and to RCR Arquitectes, Alejandro Aravena, and Wang Shu within the last decade are encouraging milestones. Advancing on this momentum is essential if the benefits of globalism’s original cultural premise are to be realized.

Li Wen is a freelance writer and former design principal at Gensler.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

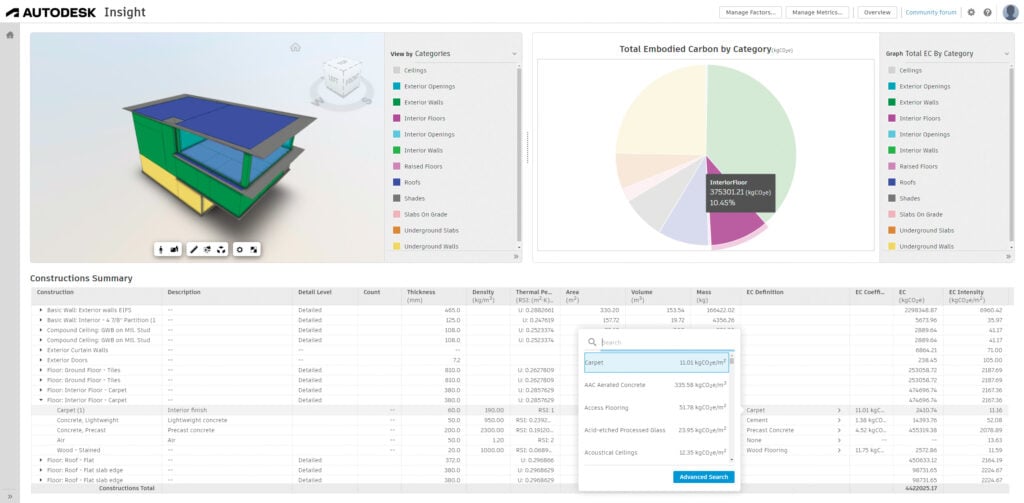

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.