June 28, 2023

Have You Been Inside a Gay Bar Recently?

In the last 21 years, 45 percent of gay bars have closed.

Greggor Mattson, author of Who Needs Gay Bars? Bar-Hopping through America’s Endangered LGBTQ+ Places

Indeed, substance use is a very real problem in the queer community. On the other hand, it doesn’t erase the significance of having an 18+ gay bar in a small southern town and how that is life changing to many. But as the story goes for many clubs and bars, Emerald City closed in 2016 over an unresolved property dispute after 18 years in business.

Why would a sober person be writing an article about needing bars? It’s simple: Gay bars are, and always have been, more than just bars. Whether you are of legal drinking age, have never touched alcohol, or are three years alcohol-free, gay bars are necessary sites of community care, and their cultural influence has spread far beyond the queer community. So then why, over the years, have so many closed?

Who Needs Gay Bars?

Over the past decade, it’s a question that has fascinated sociologists, journalists, and artists—and recent installations and book releases show it.

For Greggor Mattson, professor and chair of sociology at Oberlin College, a key theme underpinning gay bar closures is ambivalence. For his new book Who Needs Gay Bars? Bar-hopping through America’s Endangered LGBTQ+ Places (Redwood Press, 2023), the author visited over 300 bars and conducted over 135 interviews in over 39 states over six years. At the launch of the book at Manhattan’s LGBT Center, an audience member asked what Mattson makes of the amount of gay folks in recovery for addiction.

“Gay people have been ambivalent about gay bars as long as there have been gay bars. On the one hand we love them, we find them as rites of passage. And on the other hand, they are places that are organized around substance use,” Mattson responded. “One of the answers for why there are so few lesbian bars is that women organized early on in recovery meetings around cafés, coffeehouses, and non-alcoholic spaces. Addiction is one reason to be ambivalent about bars.”

And over the course of his big, gay road trip, Mattson found many other reasons: some say that both older folks don’t go out anymore and that millennials are drinking less (good for us), some attest to men and women not mixing while others say they have always advocated for all-gender spaces, a lot of them may blame the rise of social media, online communities, and dating apps while many think that apps bring more people in. It’s clear that gay bars are closing. But through his case studies, Mattson looks beyond the coasts to relentlessly question: Where? Why? When? And will they ever truly be obsolete?

“In the last 21 years, 45 percent of gay bars have closed,” Mattson said at the launch event. “Up until the beginning of the pandemic the fastest closing types of bars were bars that served women and people of color.” He points out that the media largely attributes these closures to gentrification in larger cities such as New York and San Francisco. But, as he writes in the book, “In big-city neighborhoods, it might mean a couple fewer choices…But it might mean the loss of all the bars for people of color, as happened in San Francisco, or the only club for 18-year-olds, as happened in Cleveland.” (And Pensacola.)

Honoring Black Queer Bars

Sadie Barnette is an artist who is intimately familiar with the loss of such a space. In her installation The New Eagle Creek Saloon, the Oakland-based artist reimagines and honors the legacy of the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco, owned and operated by Rodney Barnette, her father and founder of the Compton, CA chapter of the Black Panther Party.

Rodney Barnette opened The New Eagle Creek Saloon in 1990, and although it only remained open for three years, it was a space that proved “Black-owned made a difference.” In a handwritten note included in an artist-made zine of bar ephemera, there is a list of reasons why Black-owned gay bars provide the community with a place to: “practice our culture, our customs, how we socialize, our music, celebrate our history, be relaxed from white supremacy, recognize our heroes, share our experiences, contributions, and talent, reflect on our life experiences.”

Barnette writes on her website that “the bar was a space of celebration and resistance” in that it hosted fundraisers for activist groups, honored Black holidays and heroes, and participated in the historic Market Street vigils for those lost to AIDS.

While Barnette’s New Eagle Creek Saloon is a glimpse into the legacy of a bar for gay Black men, what about the lost bars for women? As Mattson pointed out, for one thing, in the early 1970s and ‘80s, lesbians were far more likely to organize away from alcohol. Reusing spaces that were not designed for them, organizing in people’s homes, and renting out church basements for community events was a common occurrence among lesbian-feminist communities.

This history is studied in depth by McGill University professor and author Alex D. Ketchum in her new book Ingredients for Revolution: A History of American Feminist Restaurants, Cafés, and Coffeehouses (Concordia University Press, 2023.) By diving into the rich legacy of lesbian spaces that were decidedly not bars, Ketchum highlights many similarities between those early DIY feminist spaces and the more hybrid queer spaces of today that may or may not serve alcohol, may or may not have a permanent location, and are open to all expressions of gender and sexuality.

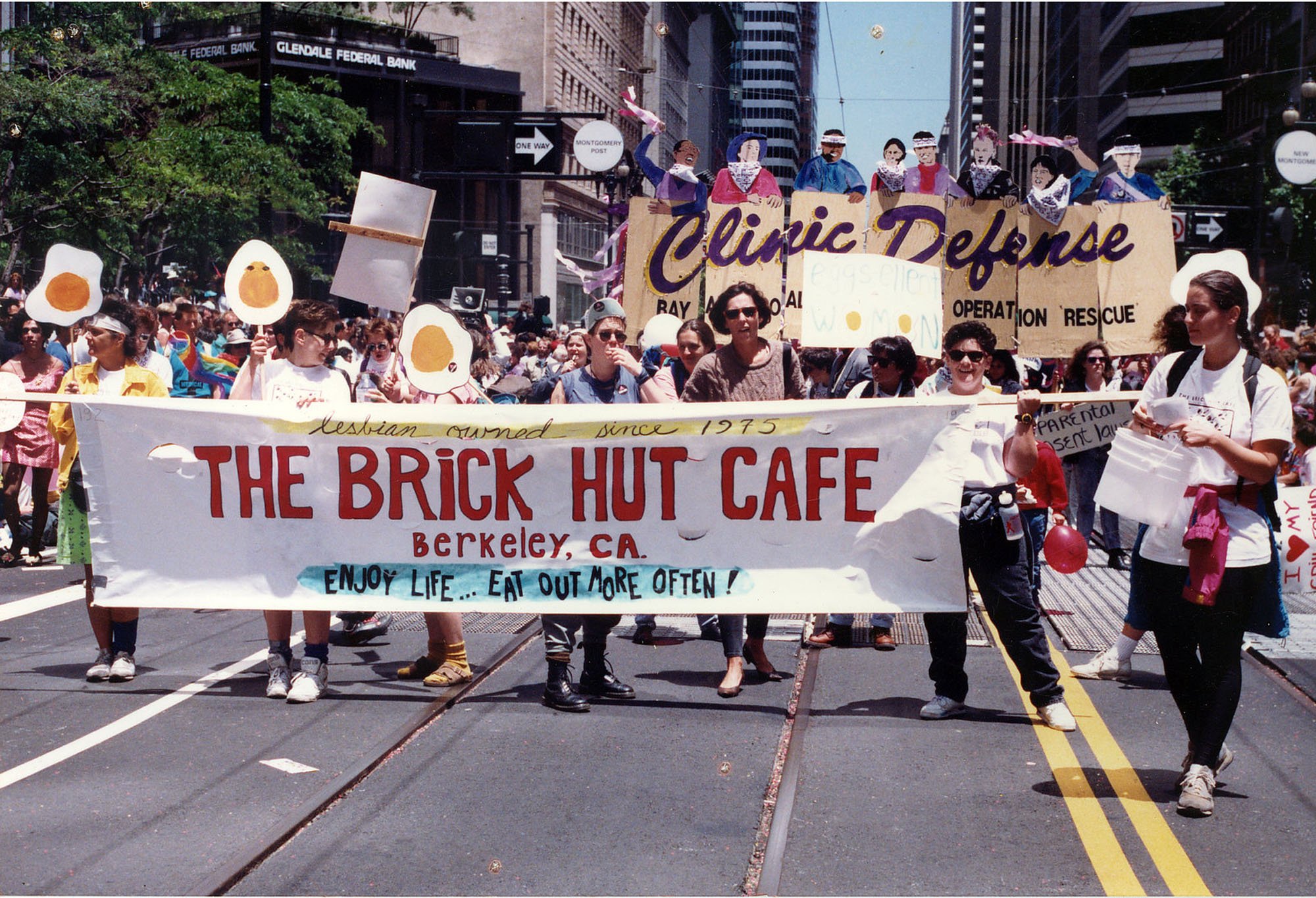

One example was Berkeley, California’s Brick Hut Café, a worker-owned lesbian feminist collective in operation from 1975 to 1997. Remembering the impact of the café, worker-owner Sharon Davenport told local food blog Bay Area Bites in 2011, “We were a haven for lesbians and gay men, an information center for LGBT activists, an anchor for a diverse community that included working girls, bad-boys, suburban queens, transmen, and transwomen. We maintained our welcome mat for the queer community and all their allies.”

Eulogy for the Dyke Bar

Just as lesbian cafes and restaurants had their peak in the 1980s, so did lesbian bars. In 1987, there were 206 lesbian bars in America and today only a couple dozen remain. Artist Macon Reed has been exploring the topic of closing lesbian bars since 2015 through their ongoing participatory art project titled Eulogy for the Dyke Bar.

In the latest addition of the installation, UNSW Sydney and the National Art School, in association with Sydney Worldpride 2023, commissioned Reed to transform the National Art School cafe into an operating bar for performances, conversation, and cruising. The “bar” drew in over 2,000 people and was activated by 11 programs and events across 10 nights, including a night highlighting the queer art of pole dancing, a night centering First Nations voices, a kink night, and an astrology night, to name a few. The space is decorated with Reed’s handmade and painted objects as well as materials and memorabilia from now-vanished lesbian bars and parties in Sydney.

Combining sculpture, installation, video, painting, and performance, the project “brings histories or communities together that have been overlooked or structurally disconnected from one another.”

Welcome to the Rubyfruit Jungle

Many spaces have taken influence from Rita Mae Brown’s classic Rubyfruit Jungle, a lesbian coming-of-age novel about a teenager leaving her conservative 1970s Florida town in pursuit of a filmmaking career and discovering lesbian culture in New York City. A notable loss is Manhattan’s Rubyfruit, a lesbian bar in the West Village that closed in 2008 after 15 years in business. According to a New York Magazine review by filmmaker Michelle Handelman, the bar aligned with what Ketchum recognizes in her book as a common lesbian aesthetic marked by a “cozy and eclectic” homey look: “With Victorian fringed lamps, red-brick walls and antique mirrors, it feels like a retirement home for diesel dykes and high school gym teachers—the only thing missing is a portrait of Gertrude Stein over the fireplace.”

A new Ruby Fruit in Los Angeles takes a slightly different approach while still maintaining a laid back atmosphere. Advertising as a “strip mall wine bar for the sapphically inclined” the restaurant/bar is brighter and filled with the warm woods, terrazzo surfaces, and pink elements that have come to define millennial interior design. Eater LA recognizes The Ruby Fruit as one of the first lesbian-owned queer bars in the area in years.

It’s just one case study showing that things might be looking up for lesbian bars. Mattson concludes, “There was a rebound and gay bars were added between 2021 and 2023. The number of lesbian bars nearly doubled, now there are only 29 in the entire country but it’s better than the 15 there were in 2019.”

Following the Yellow Brick Road

The National Restaurant Association estimates that about 60 percent of restaurants fail in their first year of operation, and 80 percent fail within 5 years of opening. The odds already don’t look great, try adding marginalized identities into the mix.

And Mattson isn’t the only one to recently scour the nation uncovering the history and legacy of the gay bar. Krista Burton’s new book, Moby Dyke: An Obsessive Quest to Track Down the Last Remaining Lesbian Bars in America (Simon & Schuster, June 2023) is a more humorous travelogue that highlights other LGBTQ+ spaces that won’t be found in Mattson’s book. Burton’s book also offers the perspective of her husband, a trans man who ventures on the journey with her. Considering how lesbian bars have largely been credited with being the most welcoming to trans and gender non-conforming folks, this is certainly a valuable inclusion into the growing literature on the topic.

Perhaps the most notable conclusion of Mattson’s research: the bars that are suffering the most now are the bars that only serve men. Does this signal that gender-segregated spaces are a thing of the past? Perhaps. Will we ever be less obsessed with the myth that gay bars are dying? I don’t think so. But as Mattson aptly concludes in his book and as these installations and openings suggest, “Gay bars are not dying, they are evolving.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Viewpoints

These 15 Must-Reads Will Prepare You for 2024

We’ve gathered some of our best 2023 articles to inspire, provoke, and galvanize you for the year ahead.

Viewpoints

Songs of Activism and Solidarity Adorn New York City’s AIDS Memorial

Artist Steven Evans’s LED installation sings out titles of anthems that defined queer liberation before and following the AIDS epidemic.

Viewpoints

What is Queer Space?

Metropolis selects over a dozen stories from its archive that celebrate the past, present, and future of queer space and LGBTQ+ designers.