October 17, 2022

The Oslo Architecture Triennale Champions the Social Dimensions of Design

“By being super local, maybe the exhibition can be relevant globally.”

Christian Pagh, director and chief curator of the Oslo Architecture Triennale

The exhibition places special emphasis on Nordic cities and the design of public and semi-public spaces. Ideas for roads, parks, pocket greenspaces, community centers, schools, and even community organizational structures are organized into sections “Understanding Places”, “Social Infrastructure”, “Our Streets”, “Naturehood”, “Reimagining Governance”, and “Alternative Practices.” A room’s worth of riotous drawings by architect and founder of Archigram, Peter Cook, accent the main exhibition with a visual reminder that urban space is in a constant state of flux and entanglement. Another central gallery space is given over to “Oslo in the Making” where 16 proposals for the next phase of Oslo’s ongoing port redevelopment project are on view.

It is this last section that’s key to understanding the exhibition’s theme and ideas. The Triennale is not shy about its local frame of reference and its relation to Oslo’s rapid and ongoing growth. Recent developments in the city center, where a major coastal highway once separated downtown from the harbor, has been diverted into a tunnel and has rightly garnered praise from environmentalists and urbanists alike. Burying the highway has opened up prime harbor-front real estate to waterfront parks and new cultural institutions such as the National Museum (2022), Munch Museum (2021), Deichman Library (2020), and Opera House (2008). Plenty of new residential development has sprung up as well, forming the mixed-use Barcode neighborhood—named for its phalanx of elongated apartment towers.

Pagh gestures to these developments in his curatorial statement, writing, “Contemporary urban development prioritizes individual comfort over what we share or could share in a community. One image way too typical of Oslo’s new neighborhoods is the oversized balcony hanging over a useless public space.”

The struggle to create a sense of place is apparent walking through the Barcode, which features plenty of public space, greenery, and ground floor retail, but was nonetheless virtually empty one September morning—save for a group of international design journalists. Why must new neighborhoods feel so sterile?

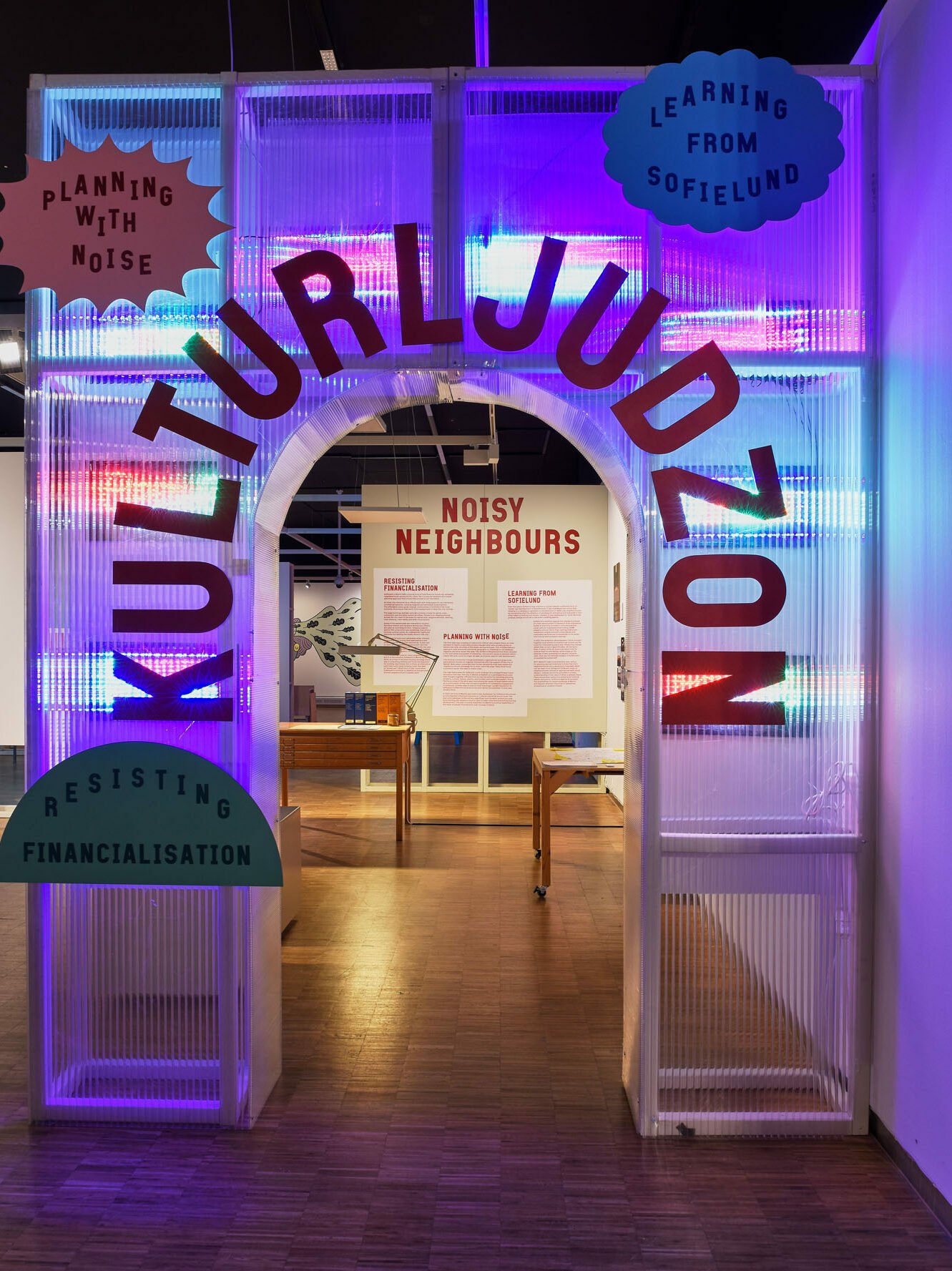

The strongest installations in the Neighborhood Lab seek to understand this phenomenon in local contexts. Among them are a new campus for the Aarhus School of Architecture, located in Denmark’s second largest city, which architecture firm ADEPT designed to serve not only students and faculty, but local residents as well. “Noisy Neighborhoods” by think tank CSAM, meanwhile, calls for the preservation of—often noisy—sites of cultural production by looking at Sofielund, a formerly industrial neighborhood of Malmö, Sweden. The study proposes a “cultural-industrial sound zone” as a new strategic tool for resisting the hyper gentrification and luxury apartment blocks that are too often the fate of these centers.

Other projects are rooted in the intimate texture of neighborhood life. “The Everyday Poetics of Daylight”, a photo study undertaken by students from the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, documents how daylight conditions in various housing units throughout the city change over the course of24 hours. Through visual repetition and variation, the photographs draw a direct connection between architecture and the experience of light—a precious commodity in these northern latitudes.

Others consider new forms of community governance. César Reyes Nájera and Céline Zimmer invite visitors to donate money and join a cooperative to lease a parking space in Oslo which the cooperative will then manage “for anything other than cars.” The experiment, aptly titled “The 10 Sqm Co-op” is not only a demonstration against cars, but a hands-on experiment in the community control of public space.

But the most radical re-thinking of who we design neighborhoods for in the Triennale may come from Matthew Dalziel, who was one of the curators of the last Oslo Architecture Triennale. Titled “Multispecies Neighborhoods” and installed outdoors, it consists of a garden of native, edible plants growing inside an earthen orb. Inspired by the ancient practice of “food forestry”—the cultivation of biodiverse ecosystems of food crops—Dalziel asks viewers to question human exceptionalism and proposes that we see neighborhoods not only as communities of people, but as multi-species webs.

Most of the projects on display were produced by teams of designers from the Nordic countries, with a few from elsewhere in northern Europe. As a result, the focus is local, and the issues addressed are not the first-order concerns like housing affordability that demand attention elsewhere in Europe and North America. That’s by design, says Pagh, who thinks of the exhibition as addressing other Nordic cities, which he points out are different enough to keep things interesting, but face similar enough challenges to make the exchange of ideas productive. “By being super local, maybe the exhibition can be relevant globally,” he hopes. After all, every city is made of neighborhoods—maybe it’s time we took them more seriously.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Spanish Firm ERRE Is Quietly Transforming the City of Valencia

With recent commissions from Marriott and Andreu World, as well as a new arena designed with HOK, ERRE is at the forefront of the city’s development.

Profiles

Emergent Vernacular Architecture Studio Builds for Community Resilience

From Haiti to Lebanon, the London-based studio helps create public spaces for those that need it the most.

Projects

Inox, Light, and Fight

At Laguna during Mexico City Art Week, fifteen architecture practices confront scarcity head-on, framing reduction, reuse, and resistance not as aesthetics, but as the operative conditions of contemporary practice.