May 26, 2022

Queer Spaces Will Always be Necessary

How does one define what queer space is when the concept of what it means to be queer itself is beyond categorization, definition, and, ideally, commodification?

But magic is mysterious, hard to pin down. How does one define what queer space is when the concept of what it means to be queer itself is beyond categorization, definition, and, ideally, commodification? Just as there is no single representation of what it’s like to be queer, or experience the world queerly, there is no single style or architectural typology that defines queer space. While much of the scholarly discourse surrounding queerness in the built environment (most notably Aaron Betsky’s seminal 1997 book Queer Space: Architecture and Same Sex Desire) can be—and is often—critiqued for centering the perspectives of cisgender, white, gay men, it appears that the idea of what queer space is or means continously gets rehashed in academia. Architecture programs across North America host queer space courses, student organizations, and symposia. But how do these ideas take shape post-graduation? Where are the queer spaces in practice? Is there a way to design queerly?

In a 2017 Q&A featured in the “Working Queer” issue of Log, Betsky ponders the “End of Queer Space?” when he tells New Affiliates cofounder, Jaffer Kolb: “My sense is [that] the physical places where queer men and women had to go to define themselves aren’t necessary anymore.” In other words, with the rise of technology, social media, and location-based dating apps, queer people no longer need to rely on underground cruising spots to find sex or community. In a largely white, western context perhaps this is true, but five years later, a new book edited by designer Adam Nathaniel Furman and architectural historian Joshua Mardell points to other truths.

Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQIA+ Places and Stories (RIBA, March 2022) proves the necessity of physical queer spaces with nearly 100 contributed projects and essays dedicated not only to cisgender “queer men and women” but also trans, nonbinary, and the full range of multifaceted identities that make up the growing acronym. The volume is an impressive step in recording these often-invisible spaces—but is by no means exhaustive. Nathaniel Furman explains, “Large parts of the world have really amazing queer scenes—but they’re not safe to be published. In a lot of countries [queer people] can do their thing, as long as they don’t shout about it.”

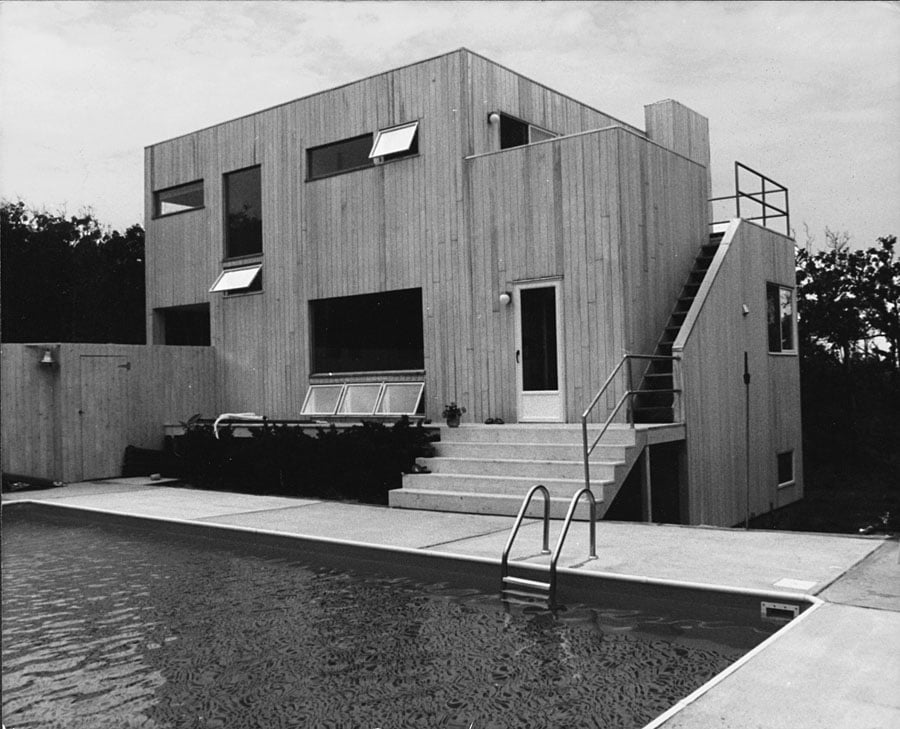

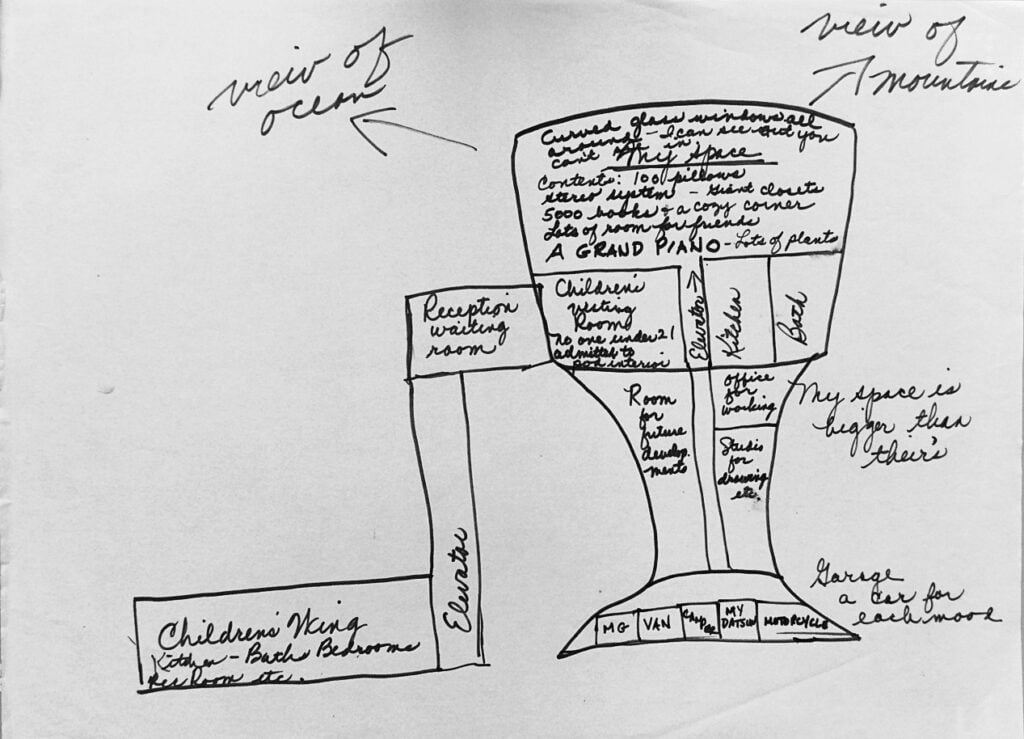

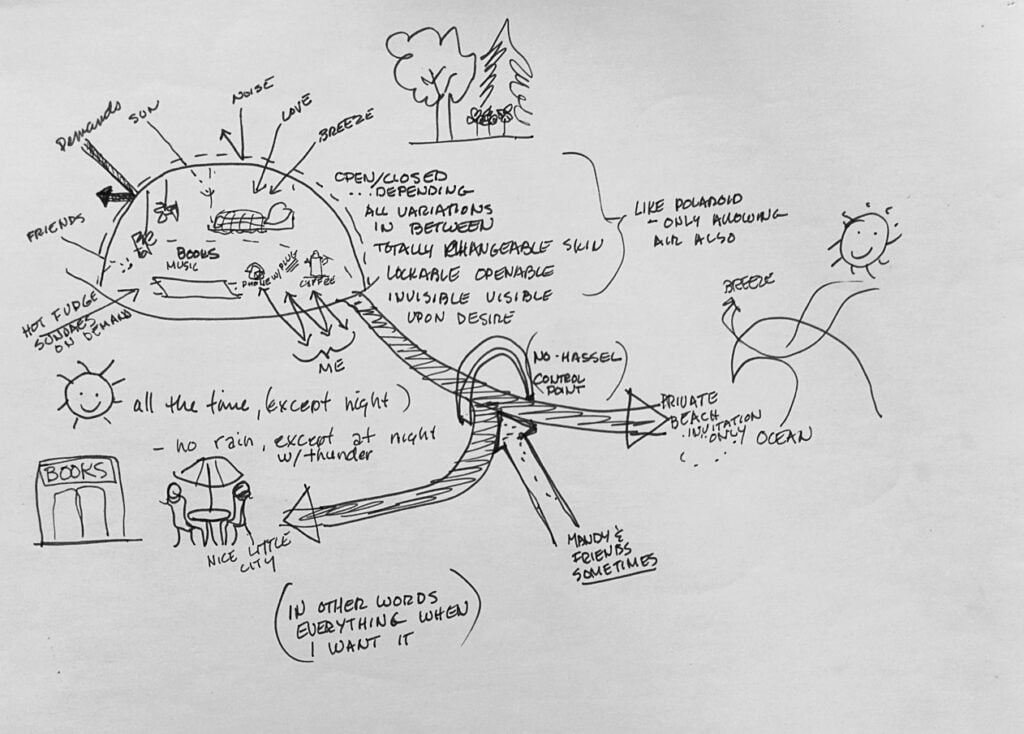

While the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” mentality has faded in the United States, the dangers of visibility persists throughout the world. The innovation that comes from the need to remain hidden is a central theme in Cornell University professor, Stephen Vider’s new book titled The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II. Expanding on the queer domestic spaces throughout the postwar United States, the book uncovers what happens when queer folks use the home as a way of reimagining the built environment as a tool to embody their desires and identities. Illustrated with intimate archival photography, the book looks at topics such as lesbian feminist architecture, community caregiving and the politics of HIV/AIDS, and the future of the queer home. For Vider, queer domestic spaces are sites of connection, care, and community and he writes, “Home should not be understood as a sealed private space, but rather a portal to the public.”

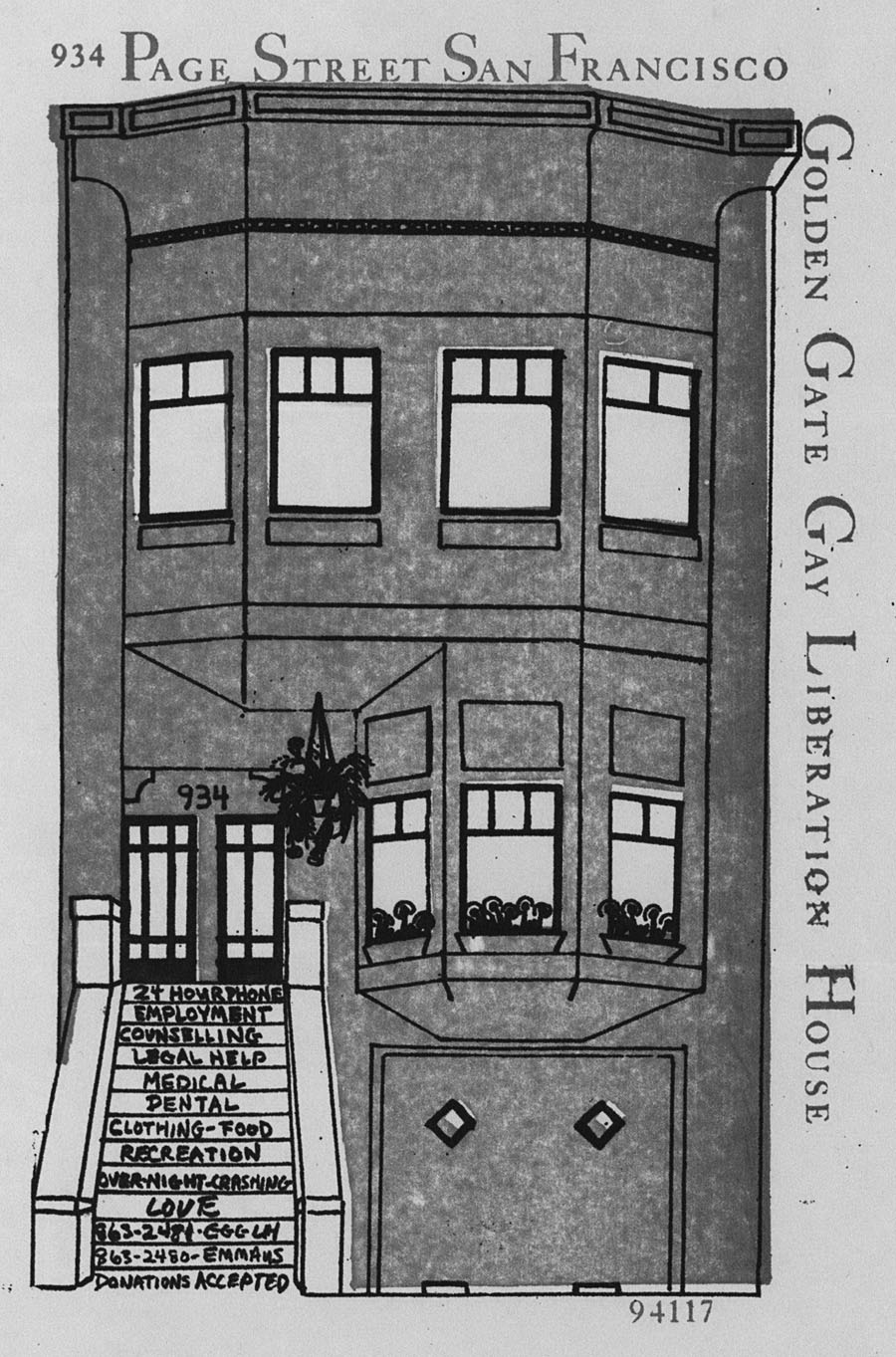

The idea of queer domestic space as a portal to greater systems of care in the public sphere is also apparent in Nathaniel Furman and Mardell’s atlas. Divided into three sections—Domestic, Communal, and Public—Queer Spaces begins with the most intimate form of architecture, touching on historic and contemporary domestic spaces such as private homes, the U.K. hotel that hosted the first transgender conference, and even an 18th-century Bavarian palace that allowed Prince Ludwig Otto Friedrich Wilhelm to pursue his same-sex desires. “The space of the domestic for those able to pool resources communally, or those in possession of wealth by virtue of class, was often where queer individuals, couples, and kinship groups were primarily able to create lasting and meaningful environments,” the authors write. “These alternative domesticities were little queer worlds that catered for those whose lifestyles were disallowed in the public sphere, where memories could be accumulated, milestones in life be celebrated, and their value as humans to one another be affirmed and marked in physical form.”

Betsky was right when he posited that queer culture has largely become mainstream—indeed, it’s no longer taboo for straight girls to host bachelorette parties at drag bars, queer shows regularly premiere on popular streaming services, and don’t get me started on corporate pride—yet, 2022 has also been a year marked by the continuous criminalization of trans kids and their families through attempts to ban access to gender-affirming healthcare, all alongside persistent attacks on reproductive rights. It’s never been more apparent that trans people—their bodies, spaces, communities—are far from being understood or accepted by everyone. While many texts on queerness and design have explored cisgender gay and lesbian spaces, Queer Spaces addresses this gap by filling the pages with the stories and images that explore transgender history across the globe including the Archivo de la Memoria Trans (The Trans Memory Archive) in Argentina, a Hijra Guru’s Rooftop in Bangladesh, and London’s Museum of Transology. As Vider writes in The Queerness of Home, domestic radical innovations “betray the circuits of power that enable and constrain them: renovation reveals the home’s wiring.”

Now, nearly three years into the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s obvious that ideas about what the home is have changed. Through digital spaces such as Zoom, our homes have become our workplaces, gyms, entertainment venues, and even doctor’s offices. While Nathanial Furman and Mardell include one example of a queer house party hosted on Zoom, it was important for the editors to not spend too much time on the virtual. “I don’t know, I just don’t think [queer virtual spaces] are as big a thing as people thought in 2015 when everyone was very excited about Grindr,” Nathaniel Furman says. “Of course, there is Telegram, Whatsapp, and Grindr and there are stories that can be made from that, but what’s [important] is meeting people in space, [and seeing] the way that we exist individually, create our homes, mark our lives. Queer spaces are everywhere, and the physical is not dying.”

Of course, with further developments in virtual reality and the metaverse, the future of queer digital spaces is, well, TBD. But just like the early excitement for app-based connection, one can hope that Web3 will usher in entirely new ways of being and expressing ourselves through design and space. Nathaniel Furman notes, “I do think the metaverse is potentially really interesting, but we didn’t position on it because it was too new when we started doing the book.”

Whether it’s the iconic Palladium Nightclub, a DIY pop-up posted on Lex, or a virtual bar you can roam with a gender-nonconforming avatar (one can dream, right?), queer space is often rooted in the ways we navigate our bodies. Whether virtual or physical, can design provide people with agency over their own bodies? What does it mean to design for visibility when so many remain hidden? How do the marginalized devise a new paradigm for design that is centered on accessibility, equality, and freedom of choice in a world that so often wants to limit our choices?

These are tough questions, and the significance of a historically heteronormative organization such as the Royal Institute of British Architects grappling with some of them through such a book should not be understated.

Perhaps, as is the point with all things queer, the questions outweigh the answers. But the LGBTQ+ community is particularly adept at noticing when something is missing, unjust, or isn’t serving the greater good. To Nathanial Furman’s point, as long as we exist, we will always need queer spaces. We will always need spaces that are fluid, malleable, and transformational. For me, the most memorable part of the atlas was when trans writer and community organizer, Ailo Ribas, describes how she uses a train ride from London to Spain to take on a more masculine presentation so she won’t be outed to her family once she arrives. She writes, “I used the train as a changing room, an escape pod: it is a locked bedroom door; a public bathroom; being home alone; a queer bar; a new outfit; a pair of breasts; a packer; a friend’s house; a support group.” Her story highlights how the way we inhabit our bodies changes how we inhabit the architecture surrounding us, concluding that, “Queer space is simply that which allows us to be in right relationship with change.” And if change is the only constant in life, well, we can all stand to learn a little bit more about thinking and building queer.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

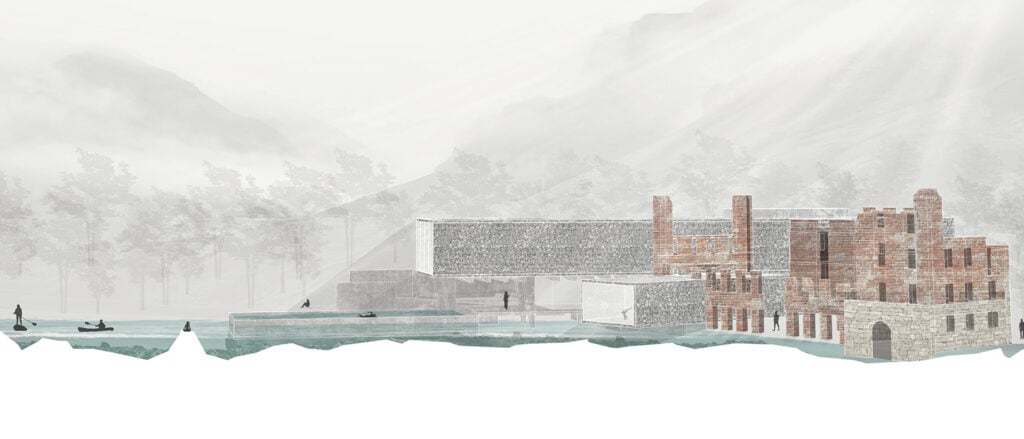

These Architecture Students Explore the Healing Power of Water

Design projects centered on water promote wellness, celebrate infrastructure, and reconnect communities with their environment.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.

Profiles

Future100: Lené Fourie Creates Adaptable Interiors

The University of Houston undergraduate student is inspired by modular design that empowers users to shape their own environments.