January 26, 2023

How a Long-dead Russian Artist Is Influencing Cultural Preservation Efforts in Ukraine

Taking Stock of the Cultural Destruction of Ukraine

Nearly a year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, reports of war crimes committed by Russian forces are filtering out of the conflict zone, and organizations such as Human Rights Watch and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe have accused the invading army of violating the Geneva Convention for, among other things targeting hospitals, intentionally killing civilians, and executing prisoners of war. Considering the wanton slaughter of so many human lives, it might seem trifling to bring up cultural preservation, but, if Vladmir Putin’s army is intentionally blowing up Ukraine’s churches, libraries, and cultural institutions, these actions could be added to the list of charges.

That’s because there is another international treaty, UNESCO’s Hague Convention, signed by 133 countries including Russia and Ukraine, which holds that when countries are at war, it is illegal for them to destroy their opponent’s cultural properties. And while UNESCO has yet to formerly charge Russia with violations of the Hague Convention, a detailed report released by the international writer’s organization PEN in early December of 2022, documents how Putin’s army’s has destroyed Ukrainian cultural sites and accuses Russia of engaging in a war of cultural erasure.

As of December 12, 2022, UNESCO has identified 227 sites throughout the country including churches, libraries and cultural institutions that have been damaged or destroyed since the start of the war this past February. Among the signature buildings on UNESCO’s list are the massive Constructivist architectural landmarks around Kharkiv’s Freedom Square such as the Palace of Industry and the Kharkiv Philharmonic.

There is some dispute over whose shells destroyed several significant sites, as is the case with the fire that destroyed the historic wooden church at the Sviatohirsk Lavra monastery, one of Ukraine’s holiest Orthodox Christian sites. However, Russian shelling appears to be wreaking most of the damage and Russian forces also have been accused of pilfering icons and thousands of paintings from Ukrainian museums.

The Idealistic Vision of Nicholas Roerich

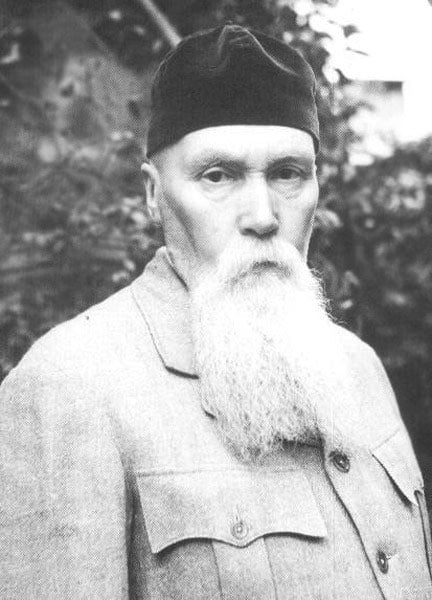

Putin’s army’s actions in Ukraine are barbaric, and they also violate maxims about the transcendent qualities of art promoted by Russian intellectuals dating back to Dostoevsky’s famous line, “Beauty will save the world,” that were later codified into a doctrine for architectural and other forms of conservation by Nicholas Roerich, the prominent Russian artist and architect. In fact, Roerich’s writings significantly influenced the development of the very international cultural preservation treaties that the Russian army appears to be currently violating.

In the early 1900s, Roerich traveled throughout Northern Russia and part of what is now Ukraine documenting and sketching historic buildings and towns. Later he petitioned unsuccessfully to get national protection for Russia’s architectural heritage. Undaunted, he traveled to the United States in the 1930s where he met with Franklin Roosevelt and proposed his idea for what became known as the Roerich Pact to the Museums Committee of the League of Nations. The pact states that historic monuments and museums as well as scientific, artistic, educational, and other cultural institutions should be considered no-fire zones in times of war.

For Roerich, the need to protect great works of art wherever they might be located superseded nationalistic concerns. “No one will dare say that the project of safeguarding the treasures of human genius is superfluous, exaggerated or useless.” he wrote in a 1931 letter, “Beyond deepening the sentiment of protection and respect for the monuments of Culture, our project offers the possibility of revising and cataloguing once more the treasures of creative power, and of placing them under the protection of all humanity.”

The Roerich Pact was initially signed in 1935 by 21 countries in the Americas including the United States, and it was a direct inspiration for further development of cultural preservation standards throughout the world such as the 1954 Hague Convention and the subsequent 1999 protocols.

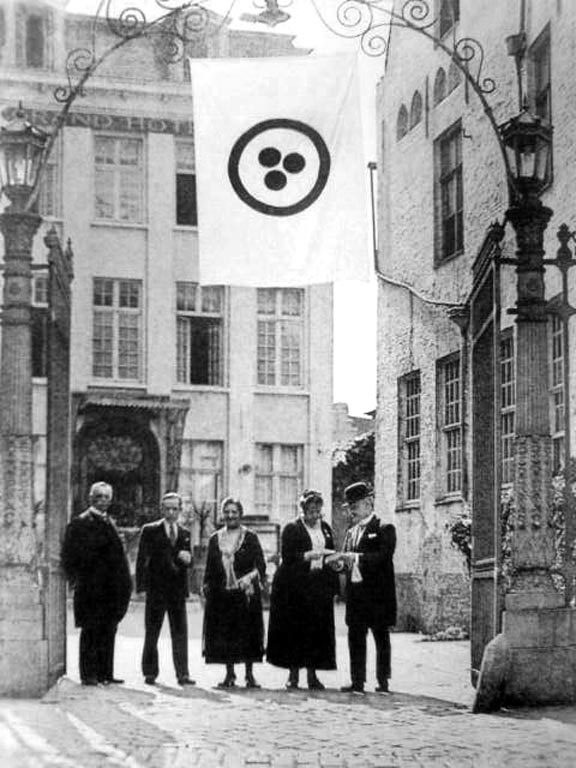

Along with his Pact, Roerich designed the “Banner of Peace,” a flag with three red dots bordered by a red circle, imagery that dates all the way back to Stone Age amulets. The Banner of Peace was intended by Roerich to be flown at designated cultural sites and places of historical value, like The Red Cross banner that is flown over hospitals during wartime.

The Roerich Pact’s Struggle for Acceptance

At the time some countries, especially in interwar Europe, viewed the Roerich Pact as idealistic and impractical. “It was impossible to implement this plan,” says Dany Savelli, assistant professor of Russian Literature and Civilization at the University of Toulouse, wrote in an email response to questions. “For example, putting a distinctive sign on a museum to protect it from air attacks (this was proposed in the pact) was from a military point of view very dangerous; it would only help the pilots of the airplanes to find their way. At least that is what the Belgian government said at the time”

Although Roerich faced widespread skepticism about his initiative, he believed eventually it would be widely accepted. “Let us remember that even the Banner of the Red Cross, which has rendered incalculable service to humanity, at first was received with derision, mistrust, and ridicule,” he said in 1931 speech at an international conference about his Peace Pact in Bruges, Belgium.

UNESCO’s current work in Ukraine bears Roerich’s imprint. The agency has helped cultural professionals on the ground safeguard certain properties with materials to protect facades and statues, identified places where endangered artworks can be moved, and advised Ukrainian authorities to place The Hague Convention’s Blue Shield emblem on endangered monuments and significant works of architecture.

The Blue Shield can be used to either indicate that personnel in the area are actively overseeing care of Hague Convention protected monuments or to indicate that certain objects, structures, and sites are protected under international law. When the Blue Shield is used three times together, it indicates that a cultural property is either immoveable, under transport, or being housed in a temporary refuge.

Roerich believed that the very act of applying safeguards to great works of art and architecture would have a pacifying effect on countries engaged in or tempted to go to war. “We are tired of destruction and of common misunderstanding,” he said in his aforementioned 1931 Peace Pact speech and, echoing Dostoevsky, he added, “Only culture, only the all-unifying conception of Beauty and Knowledge, can restore the pan-human language to us. This is not a dream!”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Products

The Anthros Chair Goes Beyond Ergonomics

A brand-new task chair comes out of decades-long evidence-based research into wheelchair design and the human body.

Projects

Monroe Street Abbey Is an Armature from the Past for the Future

Discover how Jones Studio transformed the ruins of a former Baptist church in Phoenix into a community-centered garden and event venue.