June 22, 2022

Ryan Decker Creates an Immersive Neo-Medieval Installation at Superhouse

Inspired initially by the studied and meticulous works of medieval craftsmanship, often emerging from monastic and liturgical traditions of the time, Decker also weaves in a slew of influences, from Russian science fiction films to early online role-playing games like RuneScape. Anchoring the exhibition is a video piece titled A Sedentary Pilgrimage (created under the moniker Robovine, a musical collaboration with Nikolaus Hendry) depicting a stark, disconcerting maze of a pilgrimage within an environment one cannot control. “There exists a collective fantasy in popular culture where most people get their understanding of the of the medieval era from virtual worlds like video games,” the designer says. Not one to shy away from these realities, Decker’s pieces like Relic of Yore, a floor lamp, finds itself standing on a carved wooden rock, meant to mimic the low-poly geometric stylings of early video games.

Most striking is Decker’s mastery of both the natural and artificial, turning the process of virtual renderings into tangible objects. Take, for example, his stack laminated basswood throne Bricks and Bones with a Fairy on Top, with white bronze demons poking in and out of the seat legs and armrest. “Tedious, satisfying volumetric shapes come to life in a real material, and I enjoyed working with the final material in an act of transfiguration that existed throughout the entire process,” Decker notes. Similarly, his Armet and Pocket Change table incorporates the hand-eye coordination of the mouse on the screen through tight airbrush control on the surface. A melting knight’s helmet acting as the table’s base, the whimsical forms take a turn for the biomorphic, echoing the work of Wendell Castle or Julia Krantz. Fetus Cycle, a standing mirror with implanted resin fetuses, seems to be in its own state of growth itself, as a third leg acts as a tale made of rough scales.

Equally alchemical is Decker’s treatment of his virtual illustrative work into materials like UV-printed aluminum, cast glass, and acrylic. In Mud Wizard Gives a Vision of the Future, a wizard unfolds their cloak to unveil a dystopian world in a vinyl print, reckoning with violence and turmoil, upon which witnessing one finds itself as instinctively part of, with a small round mirror placed in the center, forcing the viewer to recognize their own culpability with this Orwellian world. The taming of virtual excess is best represented in Lantern for Your Downtown Dungeon, where aluminum intersecting planes are crossed, UV-printed with insectoid, larval 3D illustrations, flattened and tamed to hold a cast glass chrysalis, suspended in time.

To embark on a pilgrimage to Feudal Relief should be with purpose to abandon preconceived notions of how the past informs the present. Rather, in a current timeline that veers wildly into antiquity and the future, there is only one answer but to account for everything to be birthed, all at once. For Ryan Decker, who toiled within his computer and workshop with monkish dedication, the destination was to ultimately reconcile what drove him to create at all.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Products

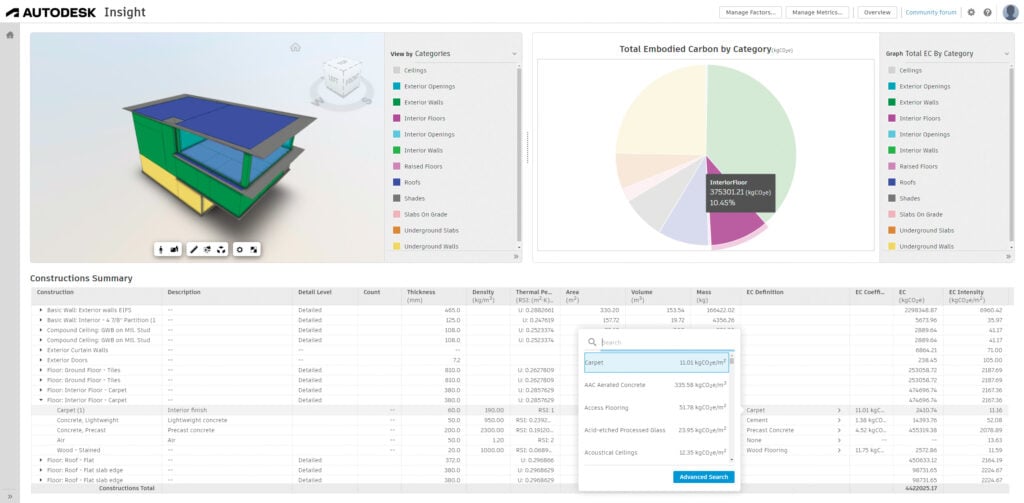

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.