July 8, 2022

Sameep Padora Untangles Mumbai’s Building Codes to Make Architecture Legible

Aastha Deshpande: (de)Coding Mumbai begins with the plague of 1896, which killed nearly 2,000 people per week that year, but you began working on this project more than two years before our current pandemic. As architectural historian Beatriz Colomina says, “More than revealing something new, pandemics expose what was already there.” How have these pandemics and broader questions of public health shaped your research?

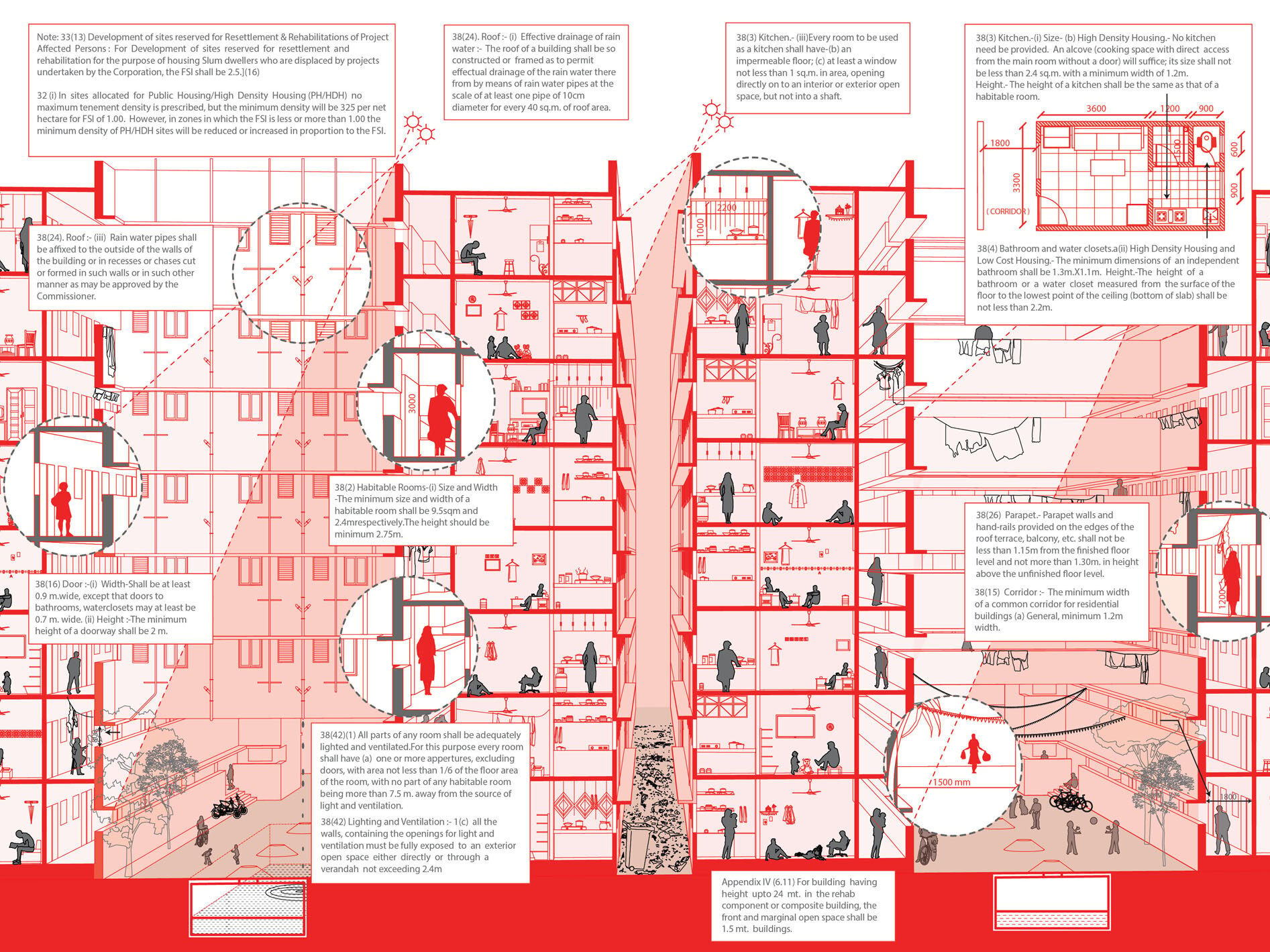

A: We started with a simple wonderment while studying housing typologies of Mumbai: All the good stuff that was built earlier, why doesn’t it get built today? This led us to the origin and evolution of building codes in the city, the earliest of which were put in place as a response to the 1896 plague. It quickly became apparent that the bylaws went from being about qualitative living environments to being purely about quantifying real estate. Health, the initial primary driver for creating these bylaws, had been forgotten by the time we reached the 1990s.

Let me put this in figures—about 60 percent of Mumbai’s population is currently living on 9 percent of its land. And if we were to apply the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) development model to that, 60 percent is going to end up living on only 3 percent of the land. These macro figures translate to densities. One in every five people in India suffer from Tuberculosis because of our architecture. That is just oppressive to say the least.

AD: In Mumbai the caste-class nexus of our societies informs the city’s spatial organization. In the midst of multiple ongoing crises—unfettered private development, new mass transit schemes, deteriorating existing infrastructure, haphazard densities, precarious sea levels, to name a few—the city’s by-laws and regulations need an urgent recalibration. How does your research and exhibition propose solutions and revisions?

SD: The bylaws are the first step to look at the living environment—the scale of neighborhoods, their livability, mass rapid transit systems that are perennially under construction, and the relationships between them. For example, building more transit is a way to subsidize housing by enabling demolition in prime areas and displacing its older (and poorer) residents to the outskirts of the city, away from their jobs and neighborhoods.

Isolation has become synonymous with luxury and elevated living, a notion that defies the very social and cultural fabric of us as a people. Developers call their projects everything from Miami Magnificence, Roman Regenza, to Las Vegas of the East, internalized coloniality at its finest.

AD: Through our plans, drawings, renderings, and other representations, architects imply an authoritative and absolute anticipation of the way people will (or ought to) use spaces. Bodies, however, are inherently disobedient, and the most architects can do is suggest a spatial organization and behavior. What are some instances in your case studies that have highlighted this phenomenon and what can we learn from them?

SP: I believe that all you do as an architect is create a framework, which if subverted through occupation, is wonderful, beautiful! After going through tendencies of authorship in the early stages of my practice, coming to this realization is truly liberating and enlightening.

In the course of our case studies, we interviewed many residents that lived in older housing typologies of Mumbai (a few of them share their stories as a part of this exhibition). A 60-something-year-old lady with severe arthritis lives by herself on the fourth floor of a chawl, a walk-up. She has another apartment to her name in a newer building with an elevator. We asked her why she chose to live how she did. She explained that “If I were to slip and fall, all I need to do is call for help. In no time there will be tens of people at my aid, flooding in through the corridor that connects us.”

It’s almost as if this entire housing block is her family, and that corridor her living room. That sense of being able to discern what is of value for you, that clarity of priorities, can only come through occupation, not speculation or control.

Q: So where do we go from here, what’s next?

A: Imperfection! Our next project is what we call “Non-Types,” where we talk about the fact that despite the heavy codification of buildings and development plans, there are models of habitation that exist in the city in defiance of all of the laws. They’ve been around as long as the Developmental Control Regulations (DCR)—around 40 years—existing because the city needs them to exist. We suggest that the future of development is not more building codes, but to allow the “Non-Types” to suggest alternatives.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

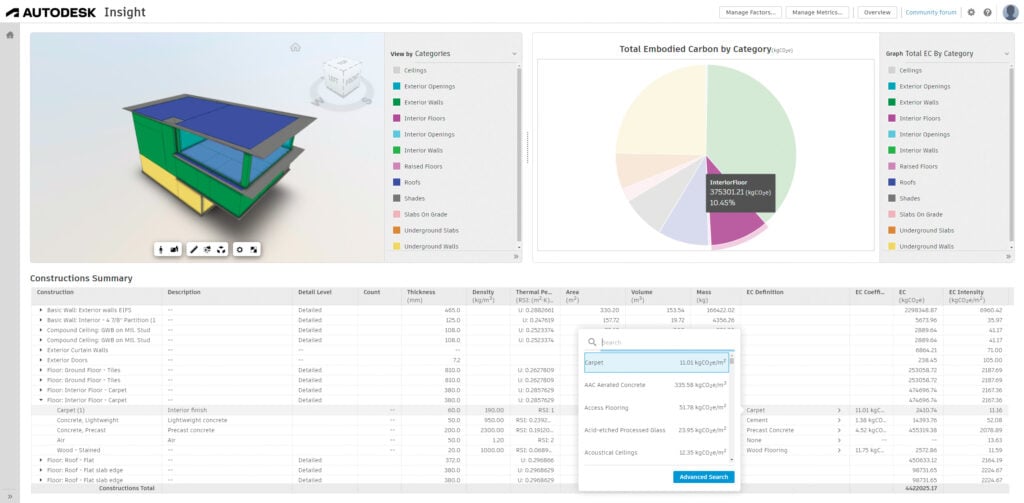

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.