July 26, 2016

Gere Kavanaugh: Pioneer With a Penchant for Color

Paul Makovsky speaks to the renowned designer about her colorful world, the collaborative and creative scene of L.A. in the ’60s and ’70s, and the power of the pencil.

Gere Kavanaugh, wearing jewelry by the Austrian designer Carl Auböck, against a backdrop of the Toy Village textile she designed in 1974 for her own company Geraldine Fabrics.

Photography by Brian Guido

Everything Gere Kavanaugh has designed—from store interiors to town clocks, textiles to furniture, and even a research room for the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum—is imbued with her trademark penchant for color, pattern, and material exploration. Metropolis editorial and brand director Paul Makovsky sat down with Kavanaugh in the Los Angeles–based designer’s studio to learn more about her life and her pioneering, multidisciplinary approach.

How did you enter the field of design?

Growing up, I liked painting and drawing and was always making things. For example, I learned about color by stacking wooden spools with colored thread on my mother’s sewing machine.

I decided to go to Cranbrook Academy of Art because I read a lot about the school through Arts & Architecture magazine. Plus, my ceramics teacher Brian Watkins at the Memphis Academy of Arts talked a lot about the school, which enticed me to go there.

I told my mother I wanted to go to Cranbrook, and she told me, “I will support you emotionally, but you have to figure out a way to get there.” I then applied for a student loan from the C. M. Gooch Foundation in Memphis, which allowed me to go.

This was in the early ’50s, right?

Yes, I was the fifth woman to go through the design studio. At Cranbrook, you really set your own program up, so I was doing mostly silk screening, textiles, and developed furniture and toys. This was a huge eye-opener for me.

So you came to school, you got your studio and dorm room, you were there for about three weeks, when Zoltan Sepeshy [then director of the Academy of Art] came into the common room and addressed the whole student body and said: “If you do not know why you are here, and what you want to do, please leave by tomorrow afternoon.” This made me realize I had to make the most of my time there. He also said that each of us was required to visit every studio at least once a week to find out what each studio was doing. So I got to see what was happening in different disciplines like architecture, weaving, printmaking, ceramics, sculpture, and so on.

Coupled with this, the Eero Saarinen office was down the back road, and so the students were allowed to visit the office intermittently to see what the office was up to. I remember seeing a lot of furniture being developed and Marianne Strengell working on textiles for General Motors.

Plus, in the Detroit area, you had designers like Minoru Yamasaki, Alexander Girard, and Victor Gruen, who made for a knowledgeable and lively atmosphere, along with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The experience of Cranbrook is very simple. There are only 125 students now. There may be 150 at the most, but 125 live on the campus. You are required to go to every studio at least once a week to find out what the other students are doing. This is a way of getting an education by osmosis. I don’t know of another school like this in the country, not even the world.

It was “learning by doing”?

Learning by being associated. You were asked to take a class one day a week as long as you went to that studio head and told them on what day you would like to work and what you were going to do and you cleaned up your mess.

My peers before me were other female designers such as Ray Kaiser (later Eames), Florence Schust (later Knoll), Carolyn Vosburg Hall, and Ruth Adler Schnee. Most of the women at Cranbrook were in other departments, like painting, weaving, ceramics, and sculpture. I became friends with the ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu and the painter Barbara Simpson Luderowski, who later founded the Mattress Factory museum in Pittsburgh, and the weaver Sisley Fiddler. There was one woman, Robbie Shook, who was in the architecture department.

The chaps from the architecture department always took weaving, because that’s where the girls were.

Once you graduated from there, what did you decide to do next?

I didn’t decide. I had $60 in my pocket. There was a lady who was the secretary assistant to the director, Zoltan Sepeshy, and her husband, Walter Hickey, who was an architect, went from the Saarinen office to work at the architecture division of General Motors Styling that coordinated the work for GM’s exhibitions, Frigidaire, and Motorola. There was an opening, and they wanted somebody to take the place of a designer by the name of Mary Loring, who was going to Europe for three months.

I was really hired to be a general flunky whose job it was to be a liaison to find things for the Saarinen office connected to General Motors. In other words, the Saarinen office called up, and it was usually Warren Platner asking for something, then I had to dig it up and get it over to them. After a few months I guess I had proved myself, and so I was assigned other projects such as designing exhibitions on cars, working on office interiors, designing small experimental kitchens for Frigidaire, and many other things.

Who were the Damsels of Design, and were you connected to them?

They were a group of female designers, most of whom came from Pratt Institute in New York, and they were largely working on the interiors of cars, doing color and styling. This was because Rowena and Alexander Kostellow were hired from Pratt to do the Kitchen of Tomorrow for Frigidaire. Rowena wasn’t going to leave any of her female students out, and she made sure that her recent female graduates were hired by GM. This was all groundbreaking.

I was connected to them in a way because I was doing the exhibitions and other projects, just not the styling of interiors for cars, which those other female designers worked on. I worked at GM for about four years.

Kavanaugh’s extensive teacup collection, with her Mood dinnerware, produced by CB2 in 2015, on the bottom shelf.

I love color, I could eat color. It’s a fascinating subject.

What happened next?

I went and worked for a year on projects like retail interiors for the department stores Hudson’s and Dayton’s with Victor Gruen in Detroit. The department stores at that time were very innovative for leading lifestyles. This was a time when there was an explosion of shopping centers being built around the country, and Victor Gruen led the way.

Eventually Gruen asked me to go out to the West Coast to work on several projects. That’s how I met Joseph Magnin and his family in San Francisco and started doing interiors for them, and I commissioned the artist Ruth Asawa to do some sculpture for the interiors of his store at Montgomery and Bush in San Francisco. The Magnins were very progressive, hiring Andy Warhol, Rudi Gernreich, and Marget Larsen early on in their careers.

It took me a year to really fathom what Los Angeles was about, because it was entirely different. You see, I grew up in an agrarian society in the South, and things were quite different. The weather in L.A., for example, meant that it was sunshine 365 days of the year, and I thought that meant I had to always be outside.

How would you characterize the West Coast mentality?

Driving out to Los Angeles was a tremendous experience for me because of the way I discovered color in an entirely different way. For example, you could see entire hillsides in magenta from ice plants or whole streets lined in shocking pink or purple from jacaranda trees and the most amazing blue skies. That whole experience was very exciting, and I had not seen that before.

How long were you at Victor Gruen’s office?

About two years, and I met Frank Gehry, Greg Walsh, and Don Chadwick and a whole bunch of other people there. The Gruen office was like being at the United Nations. There were people who came out of the Hungarian uprising; Chinese Americans like Jimmy Lim, who was a partner; Italian-Jewish engineer Edgardo Contini; and the firm was one of the first in Los Angeles to hire black designers, like Marion Sampler, who became a well-known graphic designer in the city.

It was a great place to work, and it was another turning point in my life because people like Frank Gehry and Greg Walsh encouraged me to go out on my own. Frank, Greg, and I were not given associate positions in the office, and so Frank and Greg left first. Frank went to work in Paris for another architect for a year and then returned to Santa Monica, where he and Greg established an office.

I was the first one they asked to join them, and that’s when they had a bungalow on Fourth Street in Santa Monica, and there were the three of us who rattled around there. It was so small that we kept the drawings in the bathtub.

One day, Frank calls me up, because we all lived in Westwood. He said, “I want you to come and meet me in this parking lot.” I said, “Well, OK. Whatever you say.” So I met him in the parking lot and he said, “I think we should move.” At that time, we were paying $76 a month for the bungalow. I asked how big the new space was. It was 2,000 square feet, and it was going to be 300 and some-odd dollars, and I let out a scream and said, “We’ll never be able to afford that.”

Frank looked at me and he says, “If we don’t leave now, Gere, we never will. Come on upstairs.” It was the studio of Rico Lebrun, who taught painting at Yale, and he had died recently. We had this gorgeous space, because there were bird’s-eye maple floors and we painted the whole thing white. Several years later, the graphic designer Deborah Sussman also rented space there. It was a studio where we all worked independently, but we shared the expenses, but we were all supportive of each other. We attracted an array of interesting and talented people who came to visit, like Charles and Ray Eames, César Pelli, Richard Saul Wurman, and Tony Lumsden, in addition to a collection of artists, like Judy Chicago, Robert Irwin, and Tony Berlant.

Did you guys ever collaborate on projects while you were there?

There was only one project that we collaborated on. That was Joseph Magnin’s store in South Coast Plaza, where Frank and Greg worked on the architectural interiors, Deborah Sussman worked on the graphics, and I worked on the interiors, color, and furniture.

That period from the 1960s to the early ’70s was a very rich time to be in Los Angeles, and this group basically did all the spadework for the creative and artistic community that is here now.

Let’s talk about your work during the 1970s.

I continued doing retail and restaurant interiors, and then started doing wallpapers for Bill Kielhor and Bob Mitchell. I started my own textile company called Geraldine Fabrics, where I designed and produced a collection of about eight designs in various colors where I tried to sell them through the new Pottery Barn here in L.A., and I lost my shirt and underwear with this adventure.

Kavanaugh in her studio, with a drawing of the Gere chair on the wall and an unreleased textile prototype for Knoll on the table.

At the same time, I began to do a number of exhibition designs as well. The first one was an exhibition called Islands in the Land, which was at the Pasadena Art Museum under the direction of Eudorah Moore, which looked at the traditional objects and crafts of Appalachia and the pueblos of the Rio Grande. The next exhibition I designed was called Everyday Life from the Stowe Estate, which was derived from a quarter of a million documents from the estate of the Stowe family in Wiltshire, England. The exhibition portrayed the everyday life of this English family going back to 1083.

I designed exhibitions on different kinds of themes such as costumes, Indian culture, folk art from Greece, vernacular architecture of the United States, and even one on the connection between Los Angeles and the palm tree. Also during this time, I designed the corporate interiors for several Fortune 500 companies as well as doing the interiors for the research library of President Nixon. I love designing projects that require architectural color.

What kinds of product design have you done?

I just did a line of dinnerware last year for CB2 in addition to a holiday seasonal tree and ornaments. I’ve designed everything from chairs, tables, and lighting to market umbrellas, paper goods, and even birthday cakes.

I’m currently working with Artecnica on lighting and some whimsical dinnerware, which we are hoping to produce in Mexico. I have drawers of interesting designs, and I’m looking for an agent right now. Someone once asked me, “What do you like to design best?” I replied: “Anything I can get my hands on—just ask me.”

Color is a very important factor in a lot of your work, isn’t it?

I love color, I could eat color. It’s a fascinating subject.

I’ve always done a lot of things related to color. I’ve done textiles with color. For example, when I was working with the well-known textile company Isabel Scott, I was sent to South Korea to work with a textile mill where I developed a new technique to weave Ikat fabrics and also produced a range of over 400 colors for Isabel Scott that were based on Korean ceramics and fauna. I had a hell of a good time researching and developing the colors.

I’ve taught color at Southern California Institute of Architecture and Otis College of Art and Design and places like that, but the architects always had a tendency to put it down, because they don’t know anything. That’s what was so rich about Cranbrook. You saw all of this and how it worked. There was Maija Grotell, who developed the color for the bricks at the end of each building at the Tech Center.

I remember touching those bricks with the glaze and the color. Aren’t they just amazing?

They are, but that was all because of Maija Grotell and the ceramics department at Cranbrook.

You often talk about this wall in your house where you put up things.

It is a “Brain Map.” That’s in my studio. I’m always adding and taking away from it. I keep everything from past designs that I’ve worked on, to things that will influence me in the future, and things that I just like, such as strawberry baskets or leaves that I found on the sidewalk while walking my dog.

What are you working on now?

I’m working mostly on two projects. One is to organize my archives of photographs, drawings, and articles on all my work, which is to go to Cranbrook. It has taken me two years to get to this point.

I’m also trying to help establish a Cranbrook product archive where former students can contribute their designs for products that could be produced by industry in the future, and the royalties would go back to Cranbrook.

What advice would you give to a young designer today?

Look and read as much as you can. For example, for the exhibition on the Stowe papers, I read a book called Richer Than Spices [Alfred A. Knopf, 1965], which was a history of trading, and I learned all about how indigo was brought from Asia to Europe, and so all the walls and the accents in the exhibition were done in various shades of indigo—and that was the visual glue that united all the materials. Looking and reading open the doors of imagination. You never know where your next idea is going to come from.

Also, please use a real wood pencil to draw on a big sheet of paper. It’s magic.

This wall in the studio is called the “Brain Map,” where Kavanaugh pins up drawings, past designs, and the ephemera that inspire her—down to the small green basket that strawberries are sold in. Next to her laptop is a classic watch worn by Los Angeles bus drivers.

On the mantel in Kavanaugh’s living room are portraits of her by Ruth Asawa, who also created art installations for some of Kavanaugh’s interior designs. In the foreground is a limited-edition Zinnia Flower table, accompanied by the GK Lounge chair, both designed by her.

Mini City, a tabletop toy produced by CB2 in 2015, is based on a larger version, designed circa 1965, that is now in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

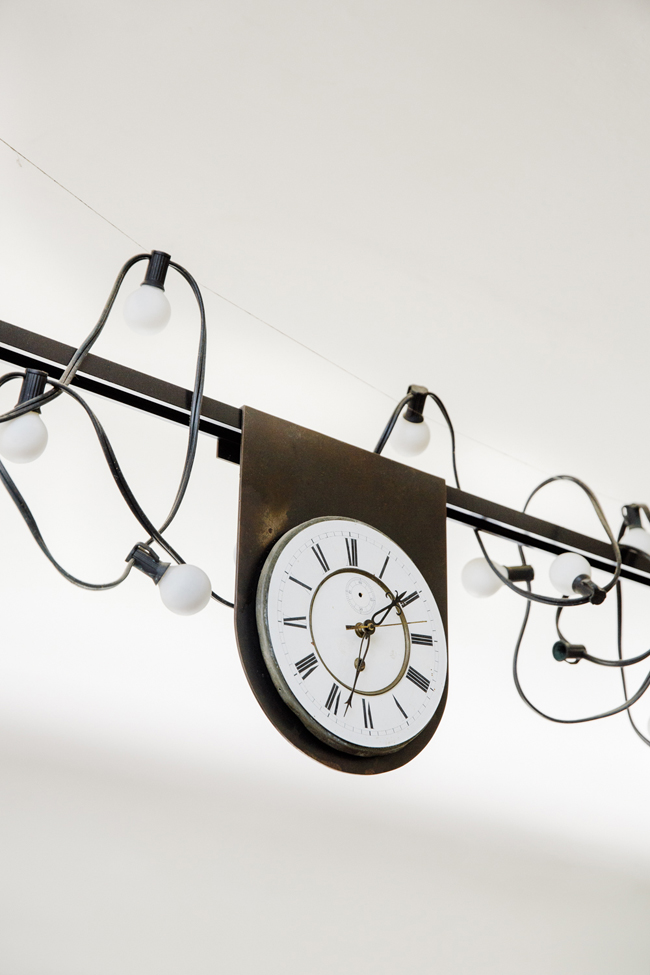

A lighting fixture with an integrated clock, designed by Kavanaugh

The Eiffel Tulip Table, fabricated by Tom Farrage in a limited edition of 10

Dove, one of three identical metal sculptures that support a glass tabletop