March 21, 2023

Rediscovering America’s First Independent Woman Architect

Just when we think we’ve become familiar with the characters of architectural history, we discover how much we don’t know. A new exhibition opening March 21 at the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania’s Weitzman School of Design will celebrate a name that only a few people have heard before: Minerva Parker Nichols. Nichols was not only the first woman in the United States to practice architecture independently, but she was a prodigious creator, ardent reformer, and brave risk taker. Metropolis editor at large Sam Lubell sat down with two of Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect’s creators, architectural historian and preservation planner Molly Lester, and the Architectural Archives’ curator and collections manager, William Whitaker, to discuss her life and legacy as well as the challenges of assembling an archive of her work.

Rediscovering Minerva Parker Nichols

Sam Lubell: Molly, you’ve been studying Minerva Parker Nichols since 2011—for more than a decade. Tell me how you got started on this long journey.

Molly Lester: As a lot of good things start, I needed a thesis topic in grad school. I’ve always been interested in how women have shaped the built environment, both formally and informally. As I searched, I came across references to Minerva, but there was very little out there. There were the drawings that the Architectural Archives hold, but beyond that and a few other scattered sources, there wasn’t much. It was tantalizing to think that there was new research to be done, that you could be contributing something worthwhile and not retread old territory.

The more I learned about her and read her essays, I got the sense of somebody who had a very clear sense of self and the way that she wanted to approach design and who she wanted to design for. There were just a lot of layers to unpack. I’d say the reason it held me in the several years that followed [my thesis] was that there were just still so many questions I wanted answers to, commissions to track down, and pieces of her life that could be uncovered. I connected with her family. I wrote a letter to a stranger because they had written one of the few sources about her, and it turns out that they were related by marriage to her family. Things like that opened up a whole other realm.

SL: It’s interesting, the idea of bringing the research beyond the realm of archives and books and into the world—talking to people.

ML: That’s necessary for a story like Minerva’s, where there were only a few crumbs, so to speak. It takes piecing together these other sources in order to understand a fuller story.

SL: Bill, how was Minerva’s history known? How was it part of your archive? What was your involvement (and that of fellow archivist Heather Schumacher), and how did that start?

WW: We got a gift of a set of drawings that had come out of an attic in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Through a colleague, Jeff Cohen, who teaches at Bryn Mawr College, the drawings wound up being deposited here. It’s one of the few sets of drawings that survived from Minerva’s work. I would often show them to students. They would ask what else she had done, and I would think to myself, ‘I don’t know enough about this person.’ It brought to mind the important role of women in design from our archives: Ann Tyng, Denise Scott Brown, Anna Halprin, and Noémi Raymond, to name a few.

Meeting Molly as a student I thought ‘Oh thank goodness, somebody will take care of this and answer the questions.’ Usually, preservation and architecture students don’t hang around that long after they graduate. They don’t keep coming back with academic interests like Molly did with Minerva. It was always exciting to hear her new discoveries and to follow what was going on. At some point we started to think about how we could do something more about this.

A Groundbreaking Woman Architect

SL: Molly, let’s talk a little bit more about Minerva, whoyou probably feel like you know at this point, I would imagine.

ML: She was born in 1862 in Illinois, and her father died in 1863. For all intents and purposes, she’s then raised by a single mother. That put her in contact with her grandfather, who was kind of a jack of all trades in building in the Midwest and instilled in her a love and interest in construction. By the time she’s living in Philadelphia, she seeks out any program in architectural education that she can. She goes to The Franklin Institute drawing school, she goes to the predecessor of University of the Arts, and she’s stitching together this architectural education. It wasn’t yet the norm that you would go to a university and get a degree in architecture, so she’s piecing together the path that a lot of her contemporaries were. But of course, she’s having to do it in an environment where there isn’t necessarily a destination that’s readily available to her as a woman. It’s not a given that anything would come of it.

By the time she’s in her mid 20s, she’s apprenticing for a few different architects, but namely Edwin W. Thorne. And that’s really where she’s getting some real-world experience and getting involved in the railroad towns that are developing along the Main Line (the western suburbs of Philadelphia). She and Edwin are responsible for a lot of projects in those suburbs as they’re coming into being. Then once you have her entering practice—we know she was in practice on her own by early 1889—she’s 27, and she establishes a specialization in residential architecture. She really starts promoting herself to audiences that are skewed towards women. She sees them as a clear advantage within her client base.

SL: It seems like she was extremely driven and that she, despite a lot of antipathy and derogatory comments and behavior, didn’t seem to be discouraged. Or if she was, she responded very well. She does seem like a remarkable person in so many ways.

ML: I think a lot of that was her personality. But I think also when you think about her circumstances—her mother is widowed, and they have a household that by this point includes Minerva and two siblings—I think she needed to contribute to the household. She needed to be successful and help earn some money. Sure, she had a strong personality and she’s negotiating with contractors and builders on the work site and things like that. But I also don’t want to downplay how much I think she needed to be a woman who could contribute household income. How much did that drive her and how much did that underpin her ambition? I think it also makes it all the more remarkable that she took the risk to go out on her own rather than take a safer path that might have raised more money.

Designing from Lived Experience

SL: She also did remarkably good work, and a lot of it. I grew up in the area, and it I imagine she had to have a huge impact on what was going up there.

ML: She’s not compromising in her designs and she’s designing homes that are meant to be presentable on all four sides as opposed to just putting everything into the front facade. She’s very clear about that in her writing. And when you look at the designs it’s clear that she’s thinking that these will be the standard bearers of design for anything that follows in those neighborhoods. She’s really trying to set a tone.

SL: I’m impressed with her practical approach, too. Just the level of detail that she was looking at, and how functional each piece needed to be. Do you have theories about how she developed that level of detail and that level of practicality in her architecture?

ML: I think that very much stems from her lived experience by that point. She had already worked as a servant, worked as a governess, worked in her mother’s boarding house. I think she had taken in a lot of points of data about how a household should function and who it could serve, and how it could improve the lives of people there. Even before she’s married and has kids of her own, she’s been very observant despite her relatively young age.

For example, in households that employed servants, she had a minimum dimension for how wide the dining room should be, so that a servant who needs to move around the table has room to negotiate that space. For households that have kids, she has ideas about how tall the stairs should be so that the kids with smaller legs can make it up and down the stairs. She also thinks that there should be bookcases that are unlocked at all times or don’t even have doors, so that kids have ready access to books. She thinks that there should not be locks on pantry-type cabinets because it establishes a measure of distrust between the homeowners and any staff that work there. Spatially, she incorporated interconnecting doors between children’s bedrooms and their parents’ bedrooms so that it’s a shorter distance in the middle of the night if there’s a child crying in bed. She’s thinking in terms of really everybody who lives in the household, and that includes servants, that includes children, it includes the parents. And because it was so often women running the household, she’s taken them all into account.

WW: There’s a strong heritage—a strong body of work around the domestic, around houses in the Philadelphia region from architects such as Frank Miles Day to Wilson Eyre, to Mellor, Meigs & Howe, and she fits within that.

A Force for Equality in Design and Beyond

SL: She’s a great marketer, she’s an incredibly talented and active architect, and at the same time, she’s this amazing reformer, too. I’m curious about that side of her. Maybe we can talk a little bit about that?

ML: I think in a lot of ways, she saw herself as a reformer in terms of creating space for women to be architects or to be involved in architecture as a profession. But she let her work speak for itself. She considered herself a suffragist and she moved among a lot of suffragists, but she deferred to them as the activists on that front while making spaces for women and designing the spaces where suffrage meetings could happen.

But she is on the platform speaking in favor of dress reform, which was a movement very much related to suffrage that promoted different conventions in the ways that women could dress themselves. Corsets at the time restricted lung capacity by up to half, and she’s supervising construction on all her projects. I don’t think it’s an accident that the one issue that we do have her on record very much speaking publicly about is dress reform. I’m convinced it’s because it intersected so closely with her day-to-day tasks and trying to navigate construction sites.

Creating an Archive Where There Wasn’t One

SL: How do you bring this to life in the exhibition? How do you portray this story of this amazing woman and this amazing work? What is your approach?

WW: We started a conversation around 2015. There were plenty of projects that we knew that still stood, but you didn’t have any historic material besides a notice here or there in the Philadelphia Real Estate Record and Builders Guide; things like that. So, you had to get a really good architectural photographer on the team, and you needed to make it a core part of the project to understand what Minerva built. I’m speaking about our colleague, photographer Elizabeth Felicella. We would be creating an archive in the absence of one. We created a process by which we could figure out what she did, and then find out if we could get access. This is all during COVID, by the way.

Elizabeth wanted to make this a HABS (Historic American Building Survey) project (HABS documents are eventually housed at the Library of Congress). We’re photographing based on Historic American Buildings Survey standards, using black and white film, not color or digital. It’s an incredibly slow process with a field camera, which is a big, clunky thing. And when you take the photograph, you don’t know if it worked. You’ve got to wait until you get the results back, and we’ve had to go re-shoot things. But the shots are beautiful. These are prints from the negatives—beautiful physical objects. We’ve documented 32 of Minerva’s extant buildings, and I think we’ve only missed two or three that we know about, just because they were a little bit too far afield.

ML: We didn’t remove all traces of current life. We weren’t creating a false scene in these spaces. I think when folks can really sit with it, they’ll see traces of magazines or children’s toys that are lying around. It will be really interesting for people to spend time at the exhibit really poring over these photographs and getting to see that time element. Based on the format they summon certain historical associations. But then the closer you look; you realize that they were taken in 2023 and that speaks to the longevity of these spaces and how long they’ve been around.

SL: And the exhibition is divided into three thematic sections, correct?

WW: The first section is that idea of her entering the field of architecture. It encompasses everything from her training, basically into the 1893 range. In parallel, she’s designing spaces for women, so we’re highlighting that as a subgroup, including a house for Rachel Foster Avery (a prominent Suffragist), the New Century Club (one of the first women’s clubs in the United States), the Queen Isabella Pavilion (an unbuilt plan for the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition), and then a series of other houses. The third section is called Minerva in The New Century, which really examines the period after she’s left Philadelphia. She’s reestablishing or reinventing the nature of her architectural practice as she enters the 20th century and continues to practice until 1940.

SL: What are some of the other objects outside of photographs?

ML: We have all these private things that teach us more about her such as family photographs and personal drawings. There are Christmas cards that her daughter drew in 1929, 1930 of the homes that she designed, which really capture the extended family’s life when they moved to a compound in Connecticut.

WW: There’s also her writing. It was pretty radical for her to be an architect and to have her own office and to be on a job site and feel comfortable telling men what to do on a job site. But it’s almost equally radical that she was writing about what architecture’s all about. She was a good writer. We’re pulling out a few of her quotes and having them be a presence in the gallery space. It’s another layer of the story that we can make visible in the gallery.

We’re just absolutely astonished at the amount of material that we were able to assemble and pull together. That’s why you do projects like this. That’s why you get a diverse team of people together who can each bring a different perspective and vantage point. And that collaborative atmosphere is always stimulating, energizing.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

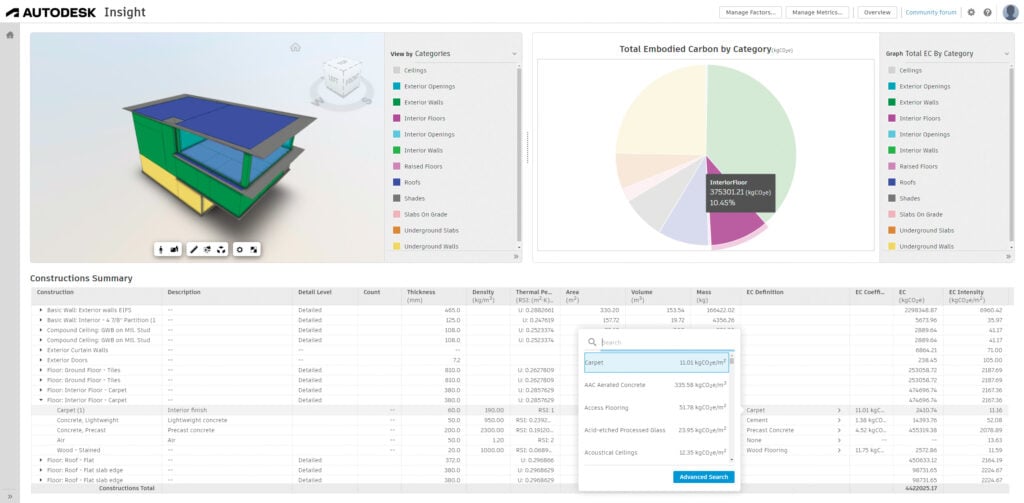

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.