July 14, 2014

Robert A.M. Stern Remembers Charles Moore

The architect reflects on his time with Moore, the pomo theorist, designer, and epicurean.

Moore House, Orinda, California, 1962

From Kevin P. Keim, An Architectural Life: Memoirs & Memories of Charles W. Moore, (Bulfinch Press Book / Little, Brown and Company, Unites States of America)

Courtesy Morley Baer

In the following text, architect Robert A.M. Stern responds to our May feature, “Why Charles Moore (Still) Matters,” with handpicked anecdotes of his friendship with Moore.

As an architecture student at Yale editing Perspecta 9/10, I first met Charles Moore by telephone and through correspondence. I had come across his amazing early projects in the Italian magazine Casabella, and was intrigued by what I read about him and his partners—especially in a provocative essay by Donlyn Lyndon. I got in touch with Charles and he volunteered that he was interested in writing about Disneyland for the journal, leading to the publication of his justifiably famous article, “You Have to Pay for the Public Life,” as well as a portfolio of projects by his firm Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull, Whitaker.

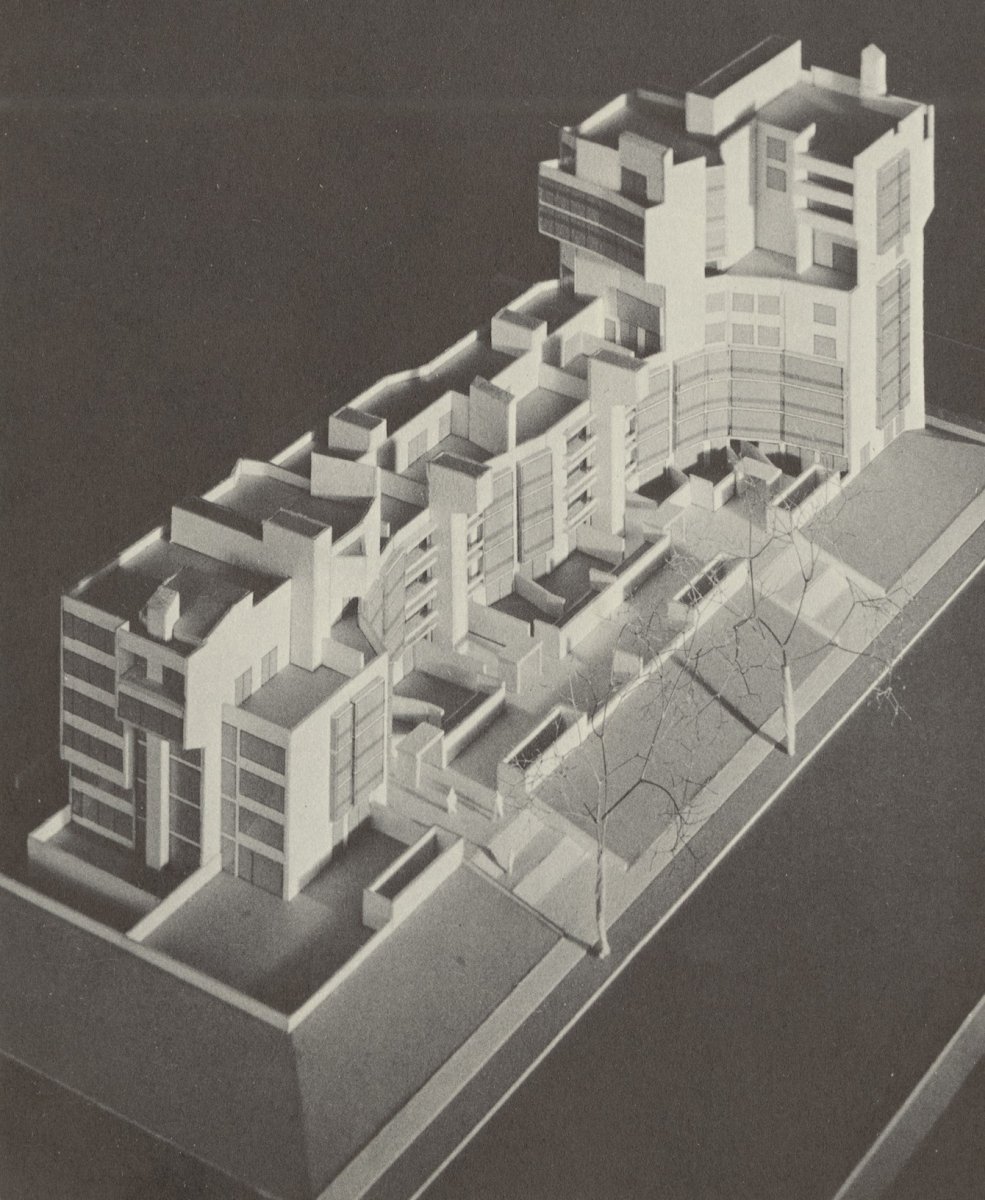

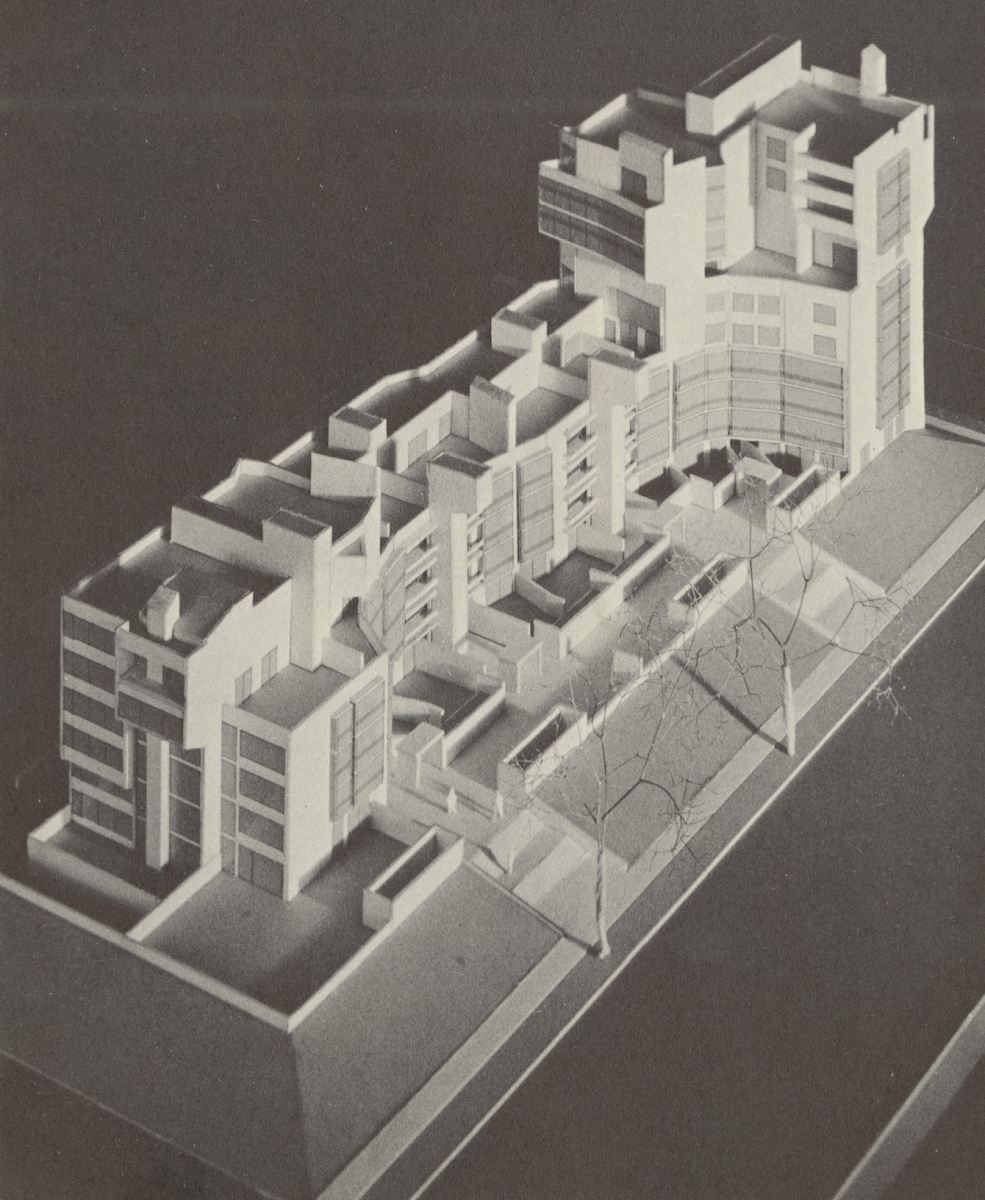

I liked Charles’s work from the very start, in particular his house in Orinda, California, with its two aedicules that were like two of Kahn’s Trenton bathhouses reinterpreted inside a larger third volume. But the Moore project that perhaps has had the most enduring impact on me was his unrealized design for a condominium in Coronado, California; instead of being either a point tower or a slab—such as virtually all high-density multifamily residential was in those days—it was a hybrid, with a wonderful domesticity about it: it didn’t look like an office building with people sleeping in it. Instead, it looked like what it was—an apartment house.

Condominium by Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull and Whitaker

From Perspecta 9/10: The Yale Architectural Journal, (Yale University Press, 1965)

Courtesy Mel Scott, The San Francisco Bay Area (Los Angeles, 1959)

I don’t remember exactly when I first encountered Charles face-to-face, but it may have been when he came to New Haven to be interviewed for the chairmanship of the department of architecture. That would have been in Spring 1965, which was approximately the time that Perspecta 9/10 was released. Charles was one of three architects interviewed for the position; the others were Robert Venturi and Romaldo Giurgola. Of the three, Charles was certainly the least well known, at least on the East Coast.

Once Charles settled in at Yale, I got to know him better. As a recent graduate, I was invited to jury reviews, and to join a committee that was organizing a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the School of Fine Arts, which had become the School of Art and Architecture. (That celebration never happened because of the disastrous fire in the A&A Building and general unrest on the Yale campus.)

Gayley Avenue, Stair

Left: Interior, second-floor area and stairs; Right: Interior, stairwell from second floor. From Charles W. Moore, Charles Moore Buildings and Projects 1949-1986, (Rizzoli International Publications, 1986)

Above and below courtesy Tim Street-Porter

Gayley Avenue, Living Room

From Kevin P. Keim, An Architectural Life: Memoirs & Memories of Charles W. Moore, (Bulfinch Press Book/Little, Brown and Company, Unites States of America)

Oddly enough, when Charles left Yale for California, I saw more rather more of him—at that time California was a welcome destination for my lecturing and a fascinating new place for me to explore. I remember staying in Charles’s house on Gayley Avenue while we were on an AIA jury. My recollection is of a ship’s cabin-like guest room at the foot of a spectacular stair that led up to his sun-filled top-floor living room. On one trip, I got to spend a wonderful day with him and others at Disneyland. When he moved to Texas, on one or two occasions I visited him in his house in Austin with its amazing curved wall lined with shelves of toys.

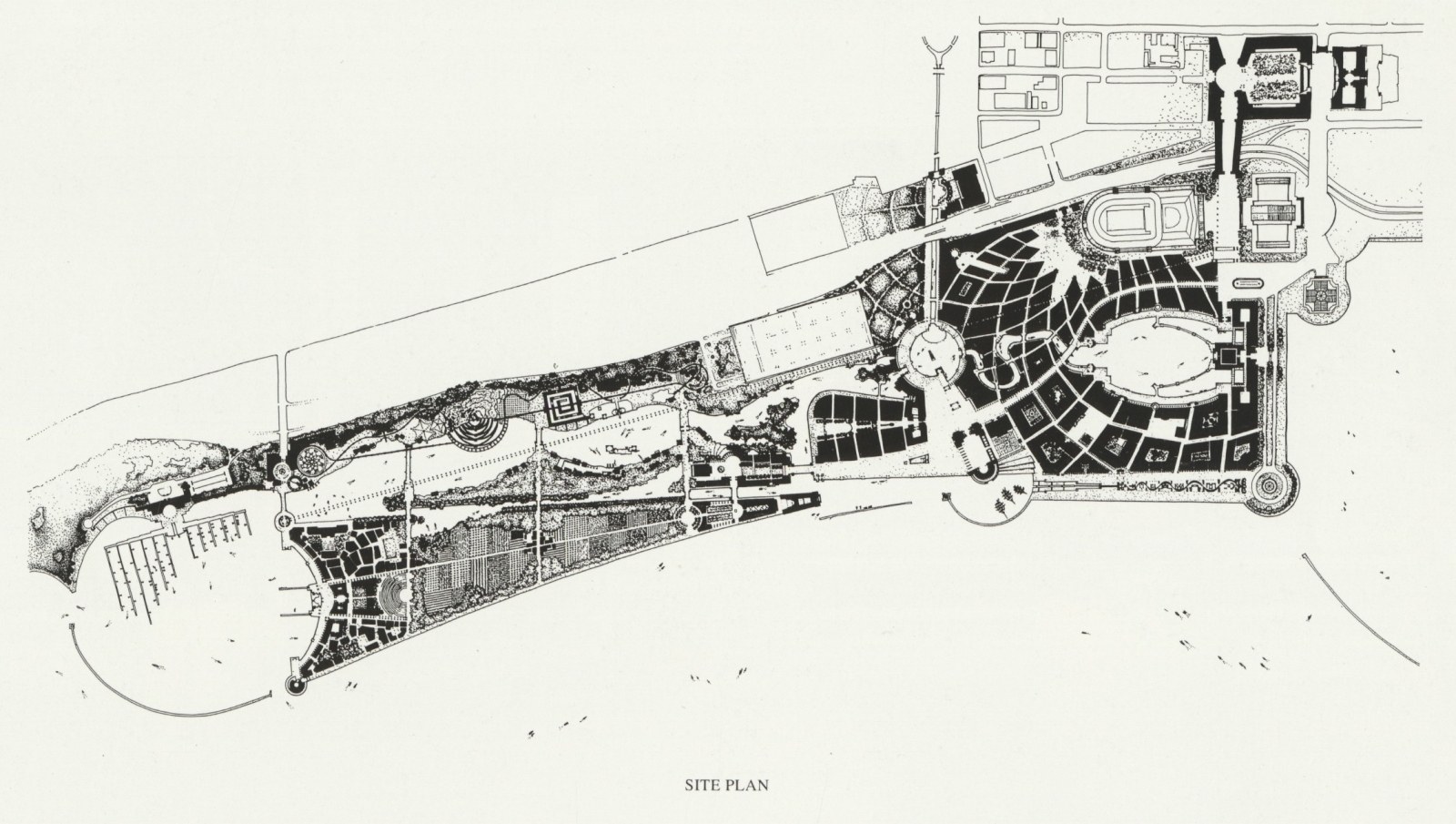

My closest work with Charles was as part of a team of architects—Stanley Tigerman and Tom Beeby among them—led by Bruce Graham of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). We were tasked with the planning of what was to have been the 1992 World’s Fair in Chicago. Charles created a plan for an area of what was then Meigs Field—he drew an astonishing latticed grid of long, curving streets that yielded spectacularly varied intersections. Charles produced a wonderful drawing (below) of his plan; I can still see it in my mind’s eye. During that time we out-of-town architects typically stayed in a great downtown club where we would gather for breakfast before embarking on our day’s work in the SOM offices. I remember those breakfasts with him vividly: Charles was not a person who watched his figure, and he would seat himself in the cavernous dining hall and dive into an enormous breakfast, taking generous helpings of chipped beef on toast and all kinds of other calorie-laden goodies. Faced with the pleasures of the table, he just couldn’t say no.

Plan, Chicago World’s Fair, by Moore Ruble Yudell working with Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, 1992

From Kevin P. Keim, An Architectural Life: Memoirs & Memories of Charles W. Moore, (Bulfinch Press Book/Little, Brown and Company, Unites States of America).

Charles had a great capacity for describing things he’d seen, to paint amazing word-pictures; that quality only partly comes through in his many books which, sadly, are not as widely read today as they should be. As Charles described a place, it was almost as good as being there—he would walk you through the streets, smell the smells, taste the food. Charles believed in travel, and he passed that love on to his Yale students, whom he charged up about the eccentric beauty of the American scene.

Robert A.M. Stern is principal of his eponymous New York-based firm and the current dean of the Yale School of Architecture.