July 21, 2021

The Potter Who Helped Shape Cranbrook Architecture

Metropolis digs into the archives of longtime Cranbrook faculty member Maija Grotell, “the Mother of American Studio Ceramics.”

In November 1971, seven former Cranbrook Academy of Art students and members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) wrote to the AIA to nominate potter and longtime Cranbrook faculty member, Maija Grotell (1899–1973), for the Craftsmanship Medal which is awarded to an “individual craftsman for distinguished creative design and execution where design and hand craftsmanship are inseparable.” When the 1971 medal was given posthumously to Wharton Esherick instead, one of the signees, Arch R. Winter, wrote back, resubmitting the nomination and urging the AIA to recognize Grotell’s critical role, not only in the history of Cranbrook but in the practice of architecture at large.

“Gentlemen,” the letter is addressed, “I talked with Fritz Woehle, member of the 1971 Jury and chairman this year, about the nomination. He was very frank in expressing to me his view that the work of Maija Grotell was not directly related to architecture and therefore did not qualify for the award,” he said, despite the AIA’s definition of crafts including furniture, metalwork, woodcarving, pottery, glassware, textiles, stained glass, and ceramics.

“Nothing is said about the crafts being architectural embellishment,” continues Winter. “While some crafts, such as stained glass, are integral with a building, others are not so directly parts of the structure. They can nevertheless enhance a structure. Pottery is surely one of these.”

Winter cites her “innovative techniques” that were “vigorous in concept and form” as a compelling argument for her inclusion among the recipients of the Craftsmanship Medal, which include George Nakashima (1952), Anni Albers (1961), Charles Eames (1957), and Sheila Hicks (1974). While a handful of women makers of the era received the medal, the only potter to be awarded it prior to 1975 was Maria Montoya Martinez in 1954.

Often described as the “Mother of American Studio Ceramics,” Grotell was a Finnish-born artist who became an American citizen in 1934 after moving to the United States to work and study under Charles Fergus Binns (“the Father of American Studio Ceramics”) at Alfred University, then called the New York State School of Clay-Working and Ceramics. Her mastery of European wheel-thrown techniques landed her teaching opportunities throughout the state and New York City in the 1920s, where her work became more informed by the Art Deco style than Finish folk art traditions.

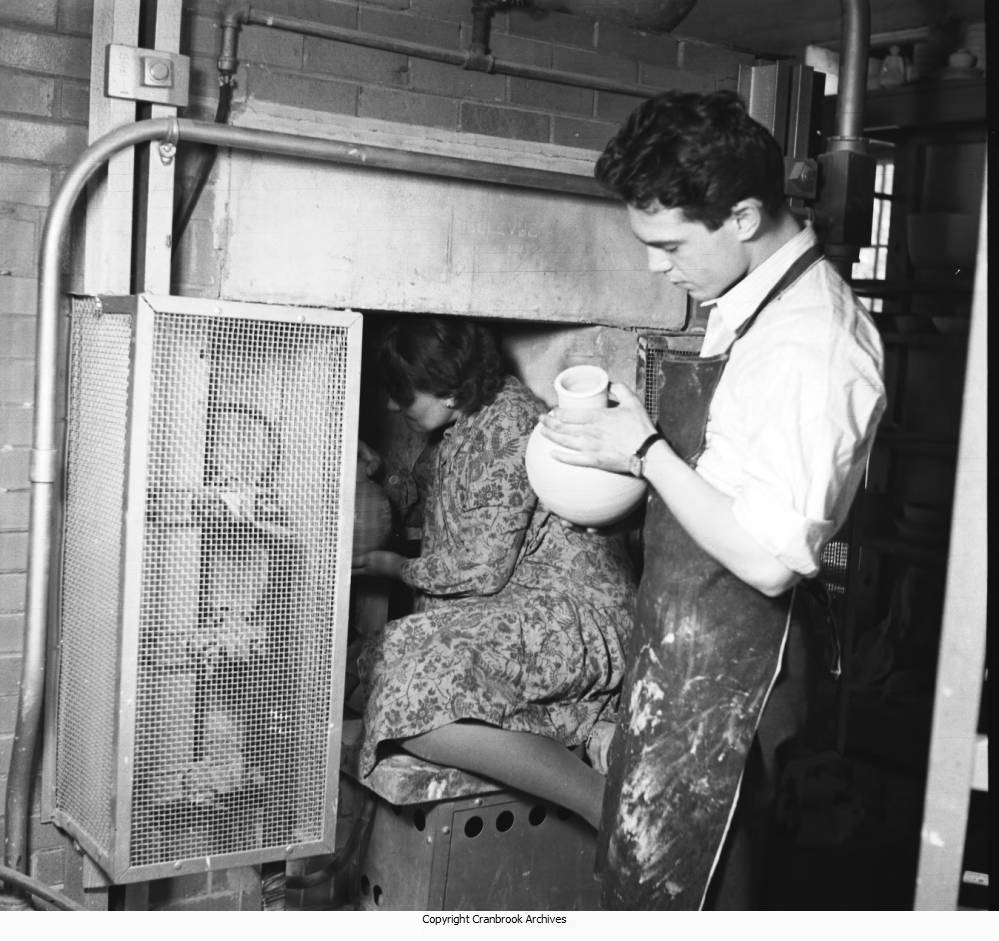

Recognizing ceramics as an integral component of architecture, Eliel Saarinen invited Grotell to become the head of Cranbrook’s ceramics department in 1938, a position she held until 1966 and a position in which she was previously declined because of her gender. Grotell changed the name of the program from pottery to ceramics, expanding the practice to not only include functional vessels but material exploration as well, such as research into glaze formulas, high-fire kiln construction, and clay bodies. She soon became known for her radical experimentation with glazes creating shades that ranged from intense blues to bright oranges.

“Her work opened the door to the architectural use of glazed, colored bricks in midcentury architecture, including those used by Eero Saarinen at the General Motors Technical Center,” writes Leslie S. Mio in the essay “Sisu, the Amazing Maija Grotell” included in Cranbrook Art Museum’s latest catalog With Eyes Opened: Cranbrook Academy of Art Since 1932. The book accompanies an expansive exhibition of the same name which is curated by museum director Andrew Blauvelt and is now on view through September 2021.

Grotell’s glaze testing for the GM Tech Center pushed the boundaries of what had previously been achieved and was available in the marketplace at the time. While Alexander Girard was the consultant responsible for the bold, primary color scheme, “Grotell formulated how to get those colors, coming up with something that would perform well for a commercial application and convinced the brick manufacturer to do this,” Blauvelt explains, “After that, you started to see a lot more of those colored brick buildings around town.”

Take a look around Cranbrook’s campus and one is sure to spot her influence in other buildings, including Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s design for the school’s Williams Natatorium (1999). The 22,000-square-foot swimming facility includes custom blue glazed brick by Nebraska-based Endicott Clay, inspired by a hue called “Grotell Blue.” Elsewhere, San Antonio-based Lake|Flato architects designed the Cranbrook Kingswood Middle School for Girls (2011) with a similar green-glazed brick and material palette reflecting Eliel Saarinen’s historic Kingswood complex.

While Maija Grotell might not be a household name in architecture like, say, Louis Kahn (who the AIA was busy awarding the 1971 Gold Medal at the time of Winter and his colleague’s correspondence). Perhaps it makes sense, how at the height of Postmodernism, the AIA could have overlooked one potter’s mark on Midcentury Modern architecture in the American Midwest. However, the longest-serving head of ceramics at Cranbrook is an important figure to not only the school but to any designers today that are looking to test the material capabilities of their projects, while enhancing space with the maker’s hand.

“There’s always been a through line at Cranbrook in terms of having a craft-based approach to understanding architecture and built space with a very material quality to it,” says Blauvelt. “Architecture isn’t simply architecture. Crafts are really central to everything here and that really starts with Maija Grotell.”

You may also enjoy “A New Book Chronicles the History of Cranbrook Academy of Art”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.