January 5, 2023

Architectural Photographer Wayne Thom and the Late-Modern Past

Because After Modernism: Through the Lens of Wayne Thom features so many familiar buildings, visitors may not realize this show focuses upon a closed and past architectural chapter. Curated by architectural historian Emily Bills and on view at the University of Southern California’s Pacific Asia Museum, Thom’s photographs capture Late-Modern works as what he called “functional sculpture” and are relics of another era when architectural photographers knew their architects personally, and architecture intimately.

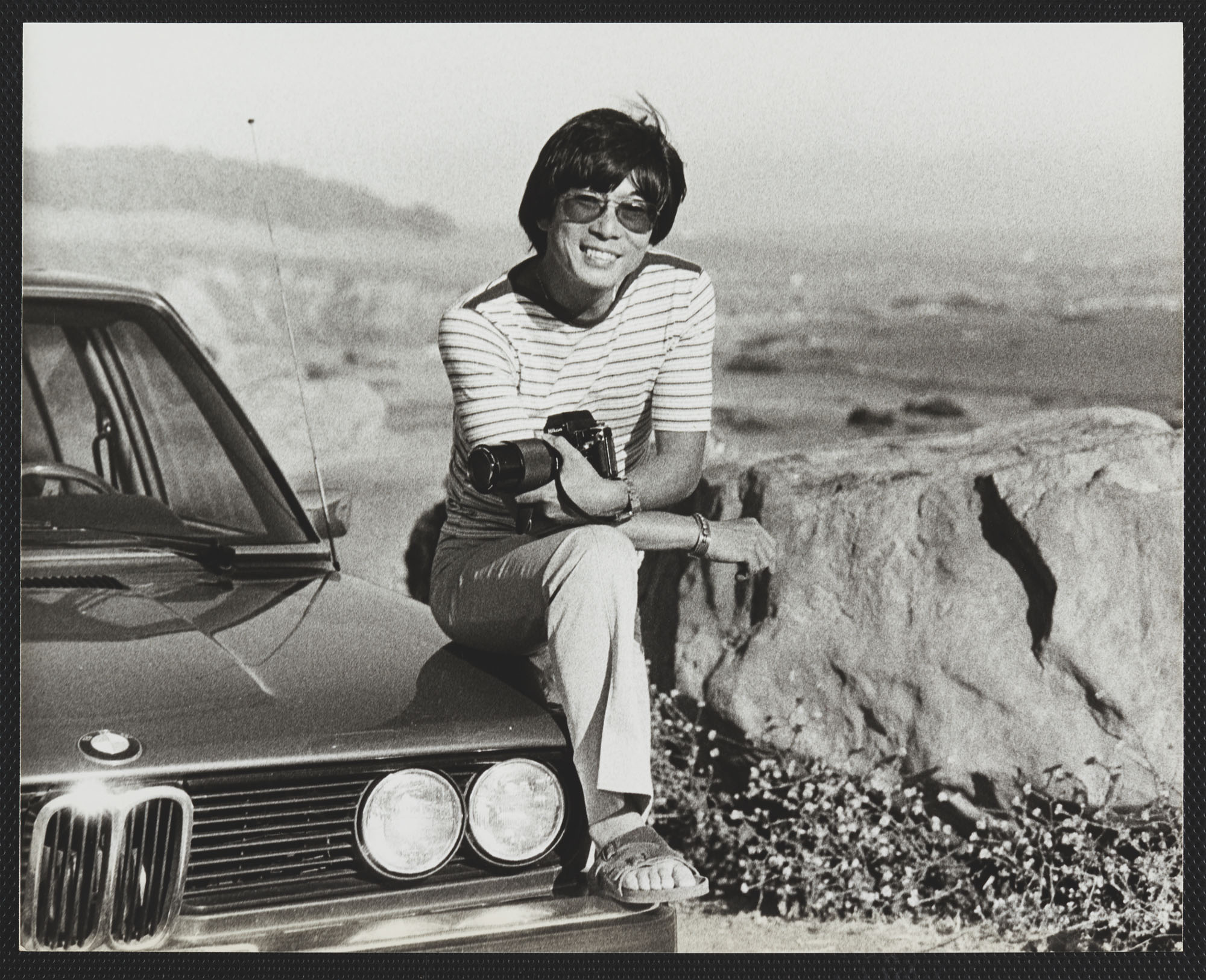

After Modernism focuses upon Thom’s Southern California work primarily between 1968 and 1988 with a few later photographs and images from jaunts up-state, across the West, to Canada and across the Pacific Rim. Born in Shanghai in 1933, Thom was raised in Hong Kong and China, and by age 15 had transformed a family bathroom into his darkroom. In 1950 his family moved to Vancouver, and for a few fun-focused years after high school, Thom served as a ski instructor at Alberta’s Banff resorts, taking pictures all the while. In the mid-1960s Thom moved to Southern California to study photography, attending Santa Barbara’s Brooks Institute on account of its hands-on, highly technical focus. Architect A. Quincy Jones gave Thom the break that launched his career in 1968, the same year he graduated.

After Modernism devotes galleries to Thom’s typologies, some more specific than others. These include interiors and exteriors of office buildings, especially skyscrapers: a Thom specialty; educational and other institutional architecture; aerospace and data facilities already lost without a trace; and smaller scale Modernist mutations of Shed Style, Organic, and Regionalist influences. Another section features Late-Modern Orange County: a then-new microcosm of the larger region’s multinucleated, non-directional sprawl.

Thom shot the signature 1970s-era projects of San Francisco and Los Angeles—the Transamerica Pyramid and the Bonaventure Hotel respectively. But many of his subjects are as invisible and anonymous as they are big. To this end, a whole gallery is filled with Thom’s sublime and intense imagery of mirror glass skin: A design system that DMJM architect Anthony Lumsden, who largely invented it, called “non-directional, non-gravitational.” Demonstrated through his spellbinding CNA Building images that featured prominently in the 1979 MOMA Transformations in Modern Architecture catalog, Thom shows that anonymity has a style after all. It is pragmatic and large but anti-monumental design informed by light, space, and the high-tech leanings of Southern California.

The subject buildings glimpse the coming computer age. But underneath it all, Late-Modernism is one of the last pre-CAD architectures of the drawing board. Such buildings and Thom’s pre-digital mastery are symbiotic, and the exhibition exudes a sense of a lost analog world. Reiterating this point is the inclusion, literally front and center, of Thom’s 50-pound, large-format Sinar camera (“Betsy the Workhorse”) he once lugged around, capturing most of what we see on Kodachrome 25 film that’s no longer produced.

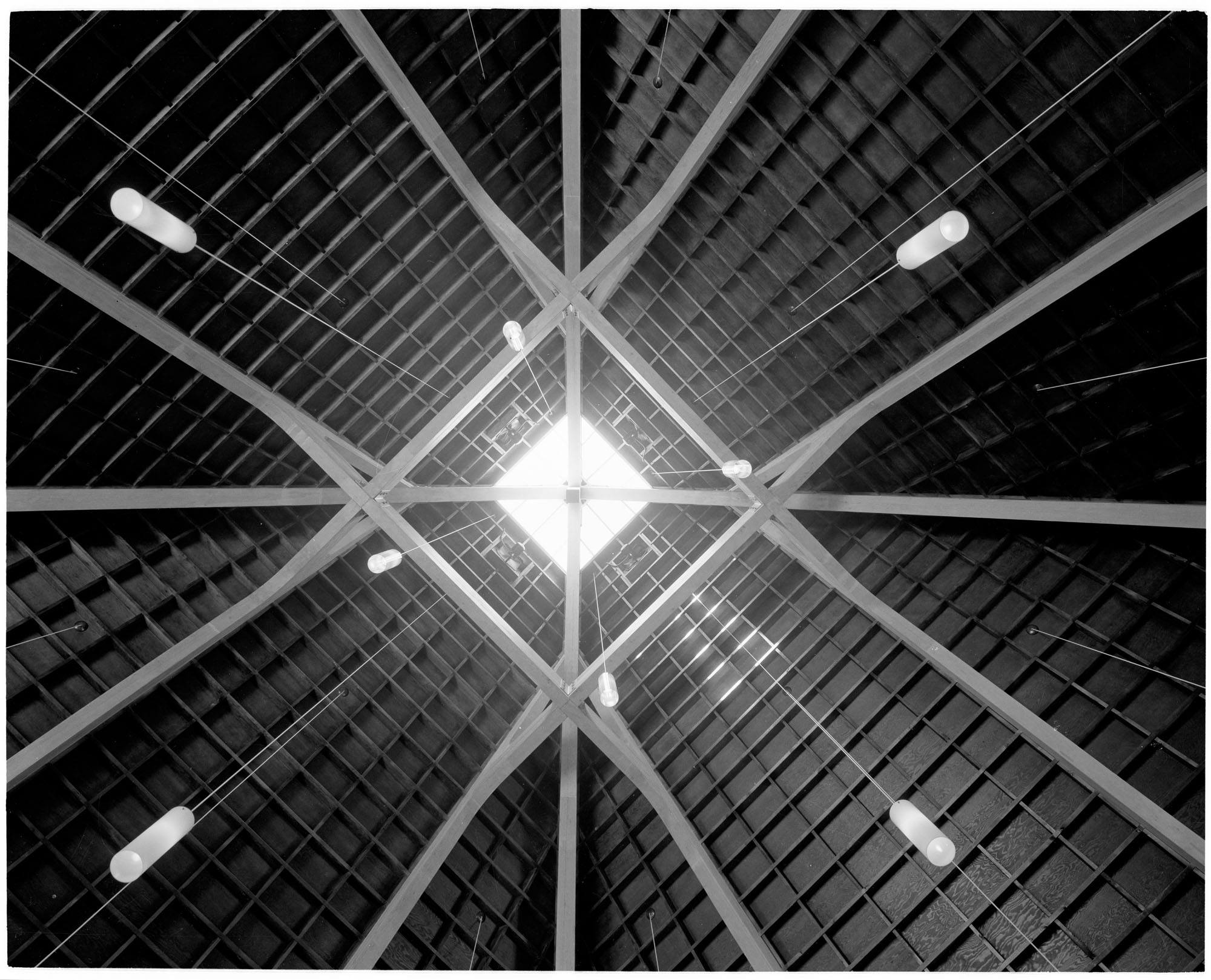

Biography bookends the exhibit’s primary galleries, with Thom’s origin story at one end and a coda space at the other with two post-1988 prints. One is a stunning wide-angle interior shot of the Vancouver Chan Centre for the Performing Arts, completed in 1997 by Wayne’s brother, noted Canadian architect Bing Thom (1940-2016). For years, Wayne was unwilling to accept money from “Brother Bing,” who had insisted on paying for Wayne’s services, and therefore Wayne never captured Bing’s work. After finally resolving this stalemate, Wayne finally photographed the Chan Centre, and the resulting image has grandeur and warmth, if not heart. Next to it, Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall—the exhibit’s last and latest project, as well as Thom’s first with a digital camera—ends one era and looks toward another. Thom retired in 2015 having photographed over 2,600 projects and produced 250,000 negatives, which were acquired by USC Libraries that same year. A digital kiosk presents Thom’s 50 favorite all-time works, and perhaps this too will get its own show someday.

For now, Bills is right to keep the focus on Late-Modernism. Evidenced by a bevy of articles and historic context statements, if not Instagram posts, this style that for the past 40 years was considered ugly, if considered at all, is now being rediscovered. But simultaneously with this reappraisal, many Late-Modern works, including some of those featured in here, are under threat from property owners, developers, and architects responding to market forces and calls to “modernize” these aging Late-Modern buildings. Bills has stated historic preservation as an impetus for the exhibition and it’s no wonder: Wayne Thom was among the very first to recognize the emergence of Late-Modernism and to gaze upon his work is to see these familiar buildings as if for the first time.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

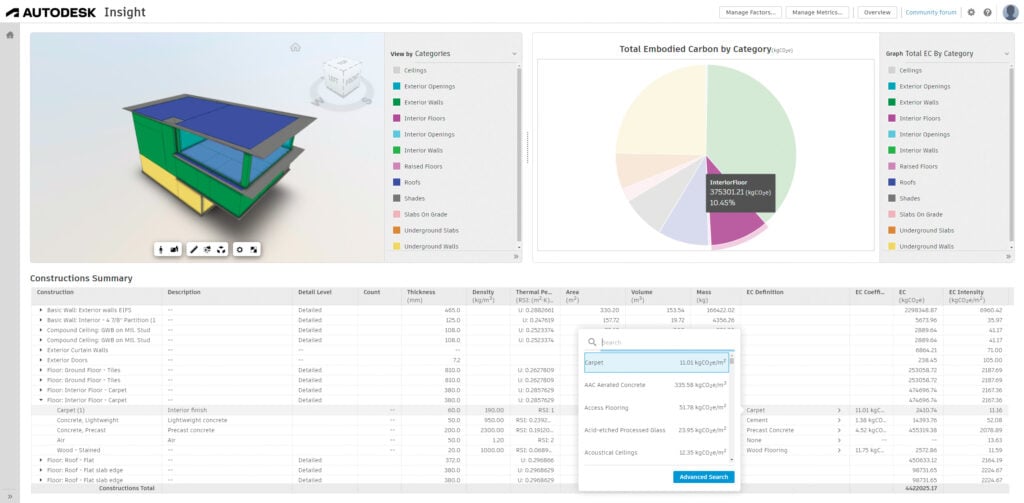

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.