February 2, 2023

A Recent Book Surveys WOHA’s Commitment to Sustainability

Singapore is close to the equator, so it is hot and humid year-round—which is great for plants, but not so pleasant for people. Air-conditioning is essential in conventional buildings, but WOHA has demonstrated a better way. It’s unlikely it would have enjoyed such success anywhere besides Singapore. A benign strongman set the country on the right course when it achieved independence in 1965, and it now has a democratically elected government. Landfills have substantially increased the size of the island, and all the land is owned by the state, which offers 99-year leases, carefully controlling the quantity and quality of development. The subway stations are marvels of cleanliness and efficiency. Every new project must reserve a quarter of the site for gardens that are open to the public 24/7. Other architects, domestic and international, have followed WOHA’s lead in making the city an inspiring model.

Each of the firm’s projects has a distinct character, but a common feature is greenery. “We see landscape as a principal feature in our buildings, not as garnish,” Hassel explains. “It is very stressful to be surrounded by hard surfaces that fill your visual frame. Greenery in the city relaxes us, as it does in a park.” Kampung Admiralty is a prime example. Two cruciform towers of apartments for seniors and a medical center are separated by a landscaped courtyard. The multi-level complex is almost hidden behind the dense plantings. Kampung means village, and it’s a model of civility, providing residents easy access to essential needs. A day care center brings young and old together, and the project adjoins a subway station so that it quickly became a social hub for the surrounding area. Singapore abounds in food halls where hawkers prepare local specialties and here one is in a covered plaza with overhead openings to a garden court providing natural light and fresh air.

The architects describe their School of the Arts as a “machine for the wind,” located in the heart of the city where open space is scarce. A lofty public plaza wraps around three theaters, doubling as a foyer and an informal performance space. The school is housed in three narrow, linked blocks above the theater, where an open-sided atrium and a library tilted inwards channel breezes through the public spaces. SkyVille @ Dawson is a social housing project comprising three 47-story towers, each broken into four linked shafts to maximize cross-ventilation and exposure to views for the 960 units. The narrow openings between them act like a fan to accelerate breezes and make it pleasant to sit outside, even in the heat of the day. The entire complex is open to the public and there is a 1,300-foot jogging track at rooftop level.

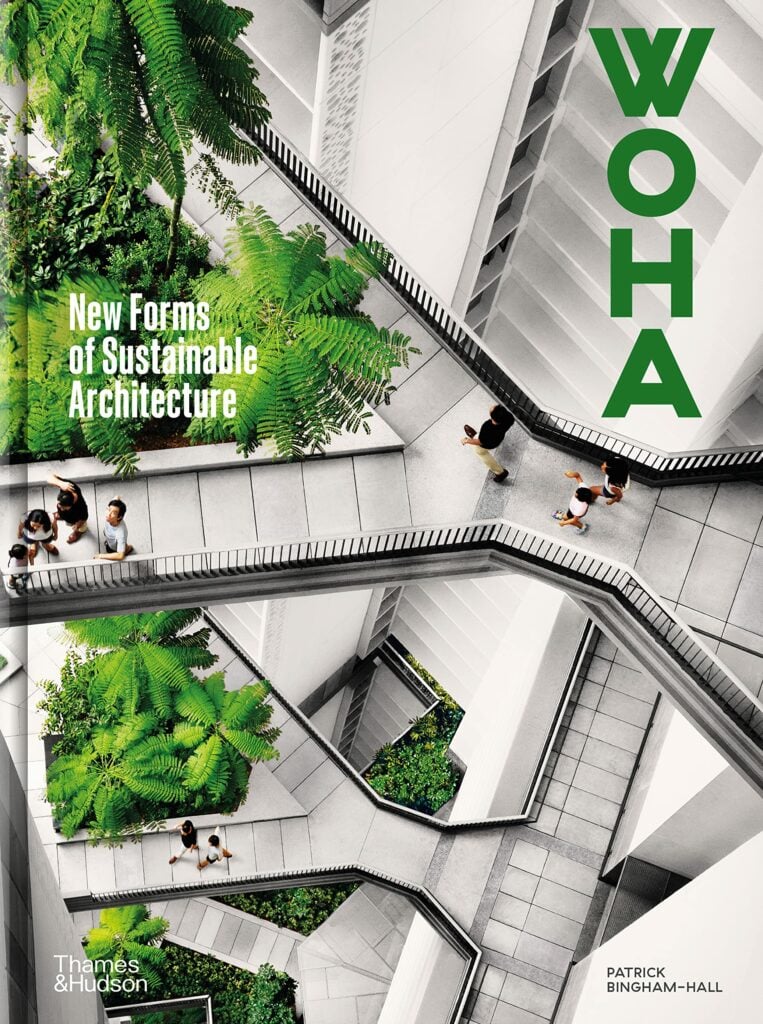

Bingham-Hall is locally based and has been writing about WOHA for years, so he analyzes its work from first-hand experience and shares the firm’s passionate concern for the environment. His monograph is a showcase of exemplary, understated buildings and enlightened ideas compromised by its abominable layout. The body type is absurdly small and overwhelmed by aggressively bold titles on almost every page. The 350 images are jammed in as though this were an overstuffed suitcase, bulging at the seams. What a pity that a book every architect and planner should read is so indigestible.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

Democracy Needs Room to Breathe

From reimagining Pennsylvania Avenue to reactivating Franklin Park, David Rubin and his Land Collective Studio are helping Washington, D.C. reclaim its public spaces as open, flexible, and deeply democratic.

Projects

The Shenzhen Energy Ring Sets a New Standard for Circular Infrastructure

The Perkins & Will–designed facility is a dynamic case study in placemaking, ensuring waste management and energy-generation become a more visible part of everyday life.

Projects

Study Architects Designs a Water-Saving Desert Retreat in Arizona

The studio’s Tucson home combines Modernist aesthetics with innovative rainwater collection to tackle resource scarcity.