July 25, 2022

A New Orleans Planner Builds Community as an Anti-Highway Activist

Activist Amy Stelly’s opponent isn’t some nefarious master planner or dictatorial governor, but a mindset obsessed with the convenience of car travel.

For the past half-decade, Stelly has waged a very vocal, somewhat lonely crusade against the highway, fighting the immense auto-centric inertia of the past half-century, as well as leery neighbors, justifiably fearful of the gentrification and displacement that might follow should the impossible ever happen.

Her career as an anti-highway activist inadvertently began in 2012, shortly after she returned to New Orleans following a stint as an urban designer in West Palm Beach, Florida. A derelict hotel was getting imploded at the corner of Canal Street and Claiborne, near the elevated, and she went to see it taken down. “There were TV stations there and I was interviewed,” Stelly recalls. “I said it had degenerated and become a seedy hotel, and was glad it was gone. Then I pointed to the interstate and said to the reporter, ‘That’s the next big thing to go.’ People thought I was crazy.”

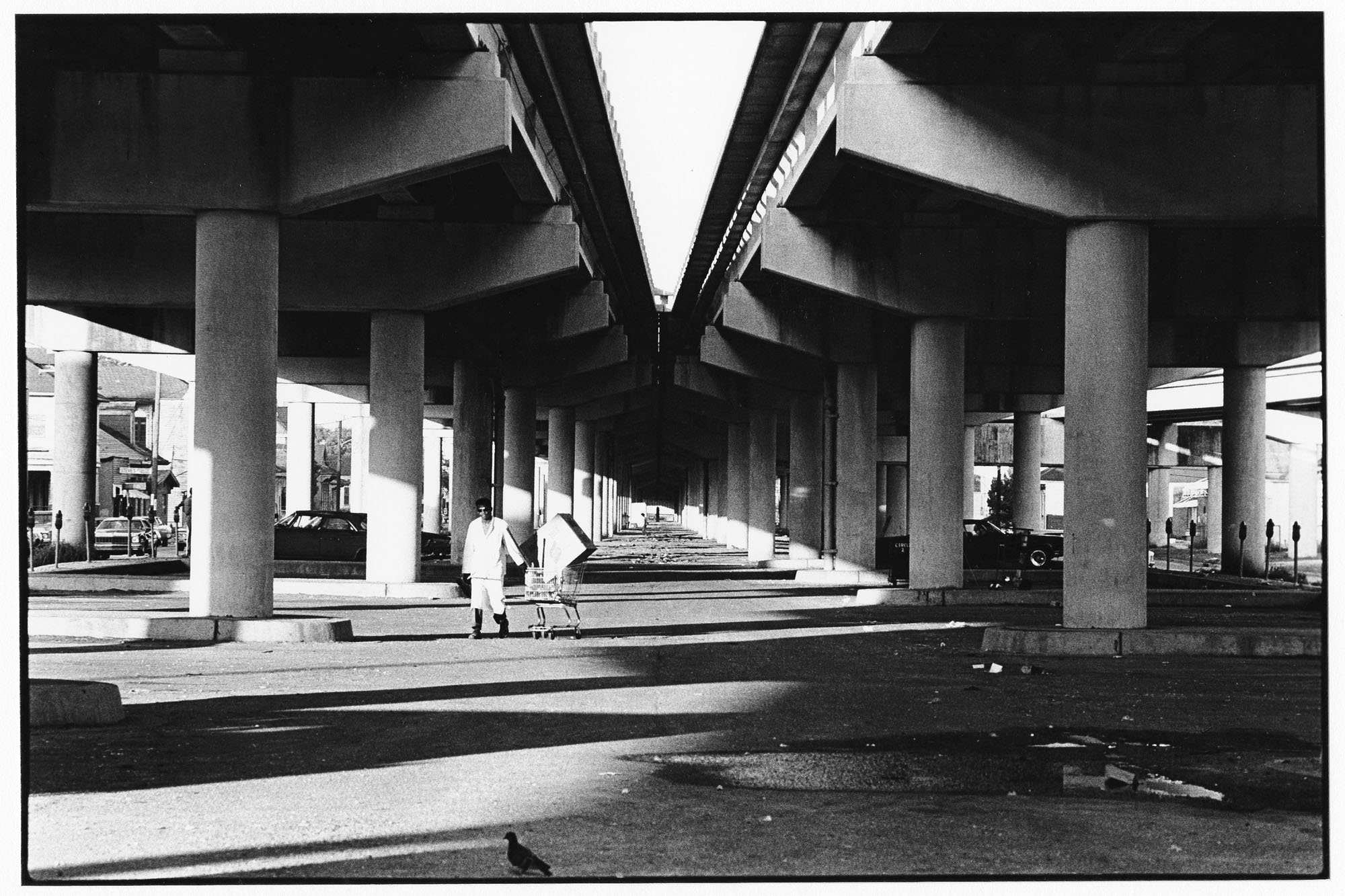

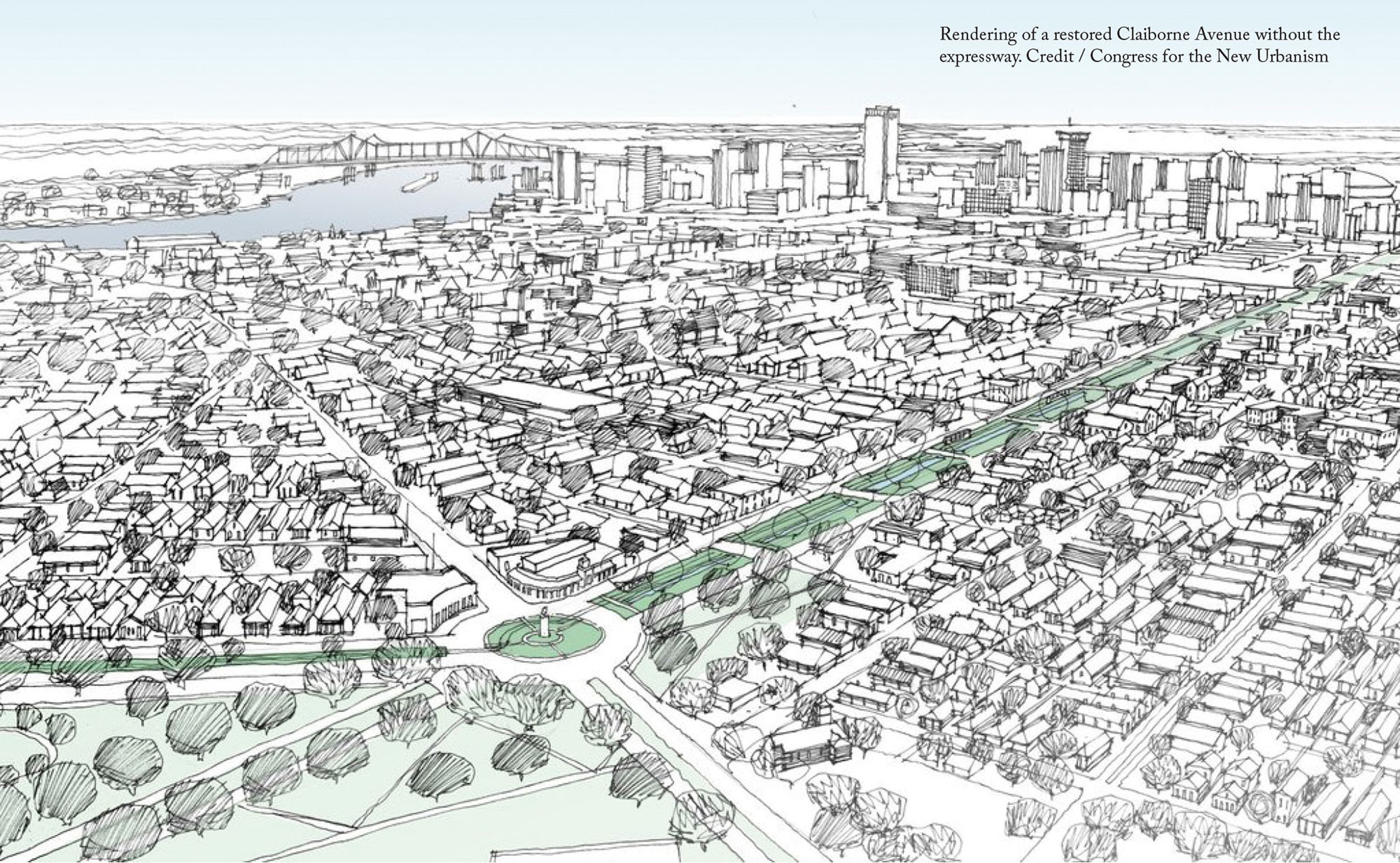

The idea of demolishing urban highways is a growing movement. Nationally more than 70 anti-highway campaigns are currently under way, but the challenge of actually removing highways is massive. It’s certainly not a new idea in New Orleans, and for good reason: The damage that the elevated piece of I-10 does to Tremé is painfully obvious. Razing it would not only right a historic wrong—the highway was, not coincidentally, constructed at the height of the civil rights movement—but free up huge swaths of land (an estimated 35 to 40 acres) and remove the hulking barrier separating Tremé and the French Quarter from the rest of the city. The 2006 Unified New Orleans Plan, the post-Katrina master plan, recommended it. In 2008 the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) named the Claiborne Expressway one of its “Freeways Without Futures.” Local CNU members—who were, it should be said, not from Tremé—lobbied for its demise. Multiple planning studies were conducted, but other post-storm priorities took precedence. Stelly became active at a moment of relative dormancy, when virtually everyone thought the idea of removing the highway had been permanently shelved. And yet some sort of action on Claiborne now seems more likely than ever, although it’s unclear exactly what that might be.

The Biden administration’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, passed late last year, includes $1 billion for the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, which will fund planning studies and capital construction projects. Obviously, the cost of repairing the damage done to our communities by urban highways will be exponentially greater. In fact, a billion dollars would likely not cover the full cost of removing the Claiborne Expressway and relinking the current bypass to needed connections to the port and the West Bank (the name for areas of the city on the west side of the Mississippi River). Still, New Orleans seems positioned to receive at least some of those funds. Former New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu serves as President Biden’s infrastructure czar; local congressman Troy Carter, a member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, recently briefed Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg on Claiborne Avenue. During a public appearance last year in support of the bill, Biden visited Claiborne Avenue and actually called for removal of the highway.

So why is removal still a long shot? Highway politics have, in the words of Congressman Carter, “a lot of moving parts”—the federal, state, and city governments, assorted elected and non-elected officials, and related government agencies, all with different goals and agendas. The necessary funding has to align with the often-shifting priorities of the various stakeholders, and that often takes years. In the past, successful efforts were led by powerful mayors (most notably John Norquist in Milwaukee, now a national spokesperson for urban highway removal). New Orleans mayor LaToya Cantrell, whose administration is currently juggling dozens of capital projects aimed at improving the city’s stormwater management, has been noticeably silent on the fate of I-10. And while Stelly says Carter came out in favor of the highway’s removal on the campaign trail, that is not yet his stated position as a congressman. “Total removal is not the only option,” he says. “It is in fact an option, but there may be other options.”

Broadly speaking, there are four main alternatives: partial removal (pulling out exit and entrance ramps, freeing up land, reducing traffic and lowering pollution), full removal, activation of the spaces underneath the highway, and repair of the highway. Stelly rejects all of them except removal, but as a planner, she is particularly disdainful of attempts at activation. (This even though, in typical New Orleans fashion, a culture of drumming emerged underneath the highway, due to enclosed acoustics.) “You can’t do placemaking under there,” she says, citing the alarmingly high levels of carbon monoxide and lead found near the highway.

Repairing the highway would probably require widening it to meet current safety standards. Not only would that double down on the harm it does to both the neighborhood and the city, but it would cost significantly more than dismantling it. To fix it would in essence mean rebuilding it. At some point, even for the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (DOTD), that math might not add up. “You don’t want to be putting big money into repairing that thing,” says architect David Waggonner, whose New Orleans–based firm Waggonner & Ball participated in previous I-10 planning studies. “Good money after bad is always a bad idea. It would be really shameful for us to do that—a tragic indication that the norm completely refuses to look ahead.” But is the DOTD ready to make that enlightened determination now?

While the federal, state, and city governments make up their minds, Stelly has formed the Claiborne Avenue Alliance. The advocacy group—composed of community members, designers, architects, landscape architects, and planners—will apply for a Reconnecting Communities planning grant to accomplish two things: drum up community support for its cause by creating a vision for how Tremé might look without the highway, and craft a community benefits strategy ensuring that the existing neighborhood won’t be pushed out if and when the highway is removed.

Stelly is moving ahead because she’s convinced that the state doesn’t have a choice. And given the condition of the highway, the uncertain future for highways in general, the state of the planet, and the unique environmental threats to Louisiana, she might just be stating the obvious: This cannot hold. It is not only unjust but untenable. But it’s a daunting challenge. Her opponent isn’t some nefarious master planner or dictatorial governor, but a seven-decade-old mindset focused on the convenience of cars—and not just in New Orleans but everywhere. Stelly isn’t climbing a steep mountain here; she’s attempting to dismantle one. No wonder the obvious looks so impossible.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Products

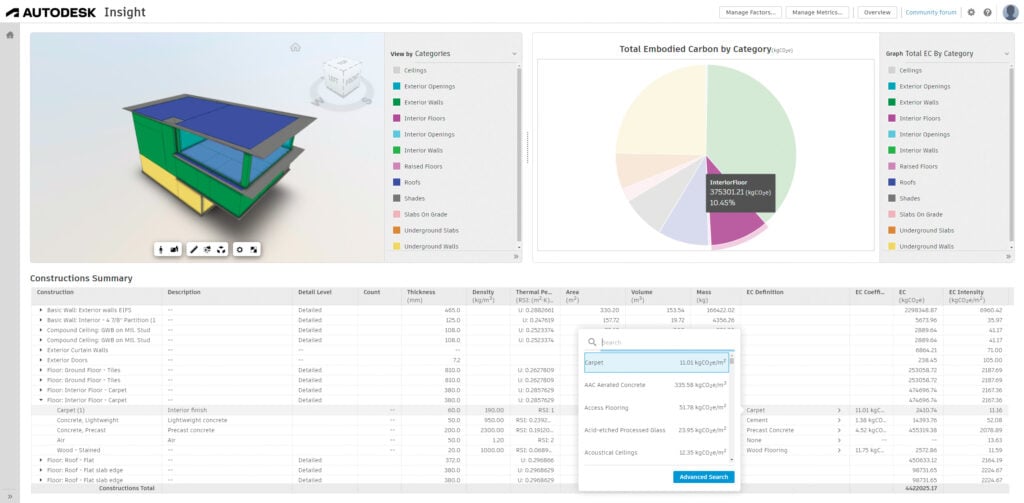

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.