February 27, 2023

Inside the High-Tech Interiors Revival

Emerging in 1970s Britain, the High-Tech Architecture movement was characterized by inside-out mechanical engineering, exposed structural systems in bold hues, and flexible interiors clad in lightweight materials with a metallic sheen. Popularized by architects such as Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, and Renzo Piano, the style constructed an ornamental language of industry and factory production where function was the aesthetic. Otherwise known as “structural expressionism,” High-Tech Architecture articulated components of construction that made structural elements appear as if they could move at any moment.

Yet these hulking steel titans paradoxically emerged at a time when technology itself was beginning to move toward miniaturization, best seen in the dawn of microchips, home computers, and global communication networks. Such advances led to computer-aided design, new material technologies, and rapid prototyping, resulting in forms that defined the “look” of technology as one of sleekness and simplicity.

Top: What does the term “high-tech” mean for designers today? For Harry Nuriev of New York–based Crosby Studios, it’s all about virtual experience, not a functionalist aesthetic. Last year, the designer launched a first-of-its-kind, digital-only clothing pop-up in New York’s Soho neighborhood for the AR fashion platform ZERO10. The innovative concept bridges digital and physical retail experiences while showcasing the designer’s signature pixelated videogame aesthetic that he has developed through both interior and furniture collections. COURTESY © ERIC PETSCHEK/ZERO10 INC.

Reconsidering the High-Tech Aesthetic

Today a new crop of designers, working in both interiors and objects, seem to be reconsidering what a “high-tech” aesthetic means for design. Diverging from post-pandemic trends that focused on natural, organic materials, these designers incorporate digital manufacturing techniques and processes while playfully engaging with the factory-made trimmings of the past.

One such designer, Harry Nuriev of Crosby Studios, known for his chromatic surfaces, pixelated videogame furnishings, and wallpapers that reference digital software, is critical of conflating technology with aesthetics. He regards the high-tech movement of the past as “a cold engineer’s functional aesthetic,” adding that today an understanding of high-tech design should be “all about virtual experience.”

Defining his practice, Nuriev recently coined the term “transformism,” a design philosophy rooted in bringing together existing objects and materials that “transmit from one thing to another,” he writes on his Instagram. Take, for example, his Video Game Stool collection, which was inspired by “how furniture looks when it’s missing quality. When you translate [physical] furniture to a virtual world, or to a video game, the file needs to be downsized.” Technology then, within its limits, produces a sort of aesthetic that does not always conform to “high-tech.” Nuriev’s own “transformist” vision of these qualities, as seen in projects like his Retro Futurism Collection, converts streamlined machine-clad motifs into soft, reflective textiles—like liquid stainless steel tenderly settling into place and becoming sofas or bedsheets.

Industrial Metaphors for the Digital Age

For other designers, factory aesthetics become the setting for larger metaphors within commercial spaces. Valencia, Spain–based creative consultancy Masquespacio’s MO Bakery and Espresso Bar in Al Khobar, Saudi Arabia, for example, is inspired by the role of water in baking and coffee brewing and utilizes metallic finishes that allude to flowing water. Sandblasted pipes climb down from the mirrored ceiling and open to become booths, recalling the pipes and air ducts that serve as entrances and lifts at Centre Pompidou. A sinuous wave of glass and chrome orbs reference gas bubbles, floating above guests and blending the shine of industry with a glossy organicism. The choice of curvilinear, sweeping forms advances the formal and structural language of the high-tech look toward a more streamlined aesthetic.

This look finds itself at home in various contexts but also thrives in spaces where its presence had never truly left. Munich-based architectural studio Buero Wagner has transformed the basement of its practice into a workspace, inspired by its own built-in industrial elements. Galvanized steel gratings are used as part of a custom-built seating area, and grated furniture is welded together rather than screwed, as if the furniture were growing organically from the ground alongside the staircase and guardrail, which are made of the same material. The effect of transparency from the grated steel is in concert with a floor-to-ceiling metallic curtain. Made of aluminum foil, the partition provides the space with natural light while also lending an element of privacy. Elements of industry refuse to be hidden: Exposed gas pipes snake around the walls alongside a staircase, and X-Beams frame the handrails overlooking the basement, perched atop a suspended steel beam. The space is versatile in use, alluding to the dreams of flexible, open-plan interiors of the High-Tech architectural age, where partitions can create zones for specific use rather than permanent rooms.

Reinterpreting High-Tech’s Ecological Motivations

Czech architecture studio CHYBIK+KRISTOF’s newest structure, the Modular Research Center for capsule and modular architecture manufacturer KOMA Modular, embodies this desire for flexibility. Envisioned as an “innovation hub” to prototype modular building methods, the project blends elements of High-Tech Architecture and digital design. The center is constructed via rotating containers that function as structural columns and is unique in its omission of right angles. Rather than insinuating a sort of structural impressionism of movement via support elements or construction systems, the rotating containers turn the campus into a true living machine to solve problems in an instant, in the spirit of Cedric Price, who famously commented that architecture “is too slow to solve problems.” The project, constructed via three main modules (roof, container, and floor), is resplendent with shiny load-bearing walls, accentuated by floor-to-ceiling windows that allow natural light to come in and reflect off the perforated metal ceilings.

Reiterating the roots of High-Tech Architecture’s own ecological motivations, the materials used to construct the Modular Research Center are locally produced. These elements emphasize the structure as a living, ever-changing module, in line with the values of the client in promoting human activity and movement through thoughtful structures.

The Next Generation of Ultramodern Objects and Furniture

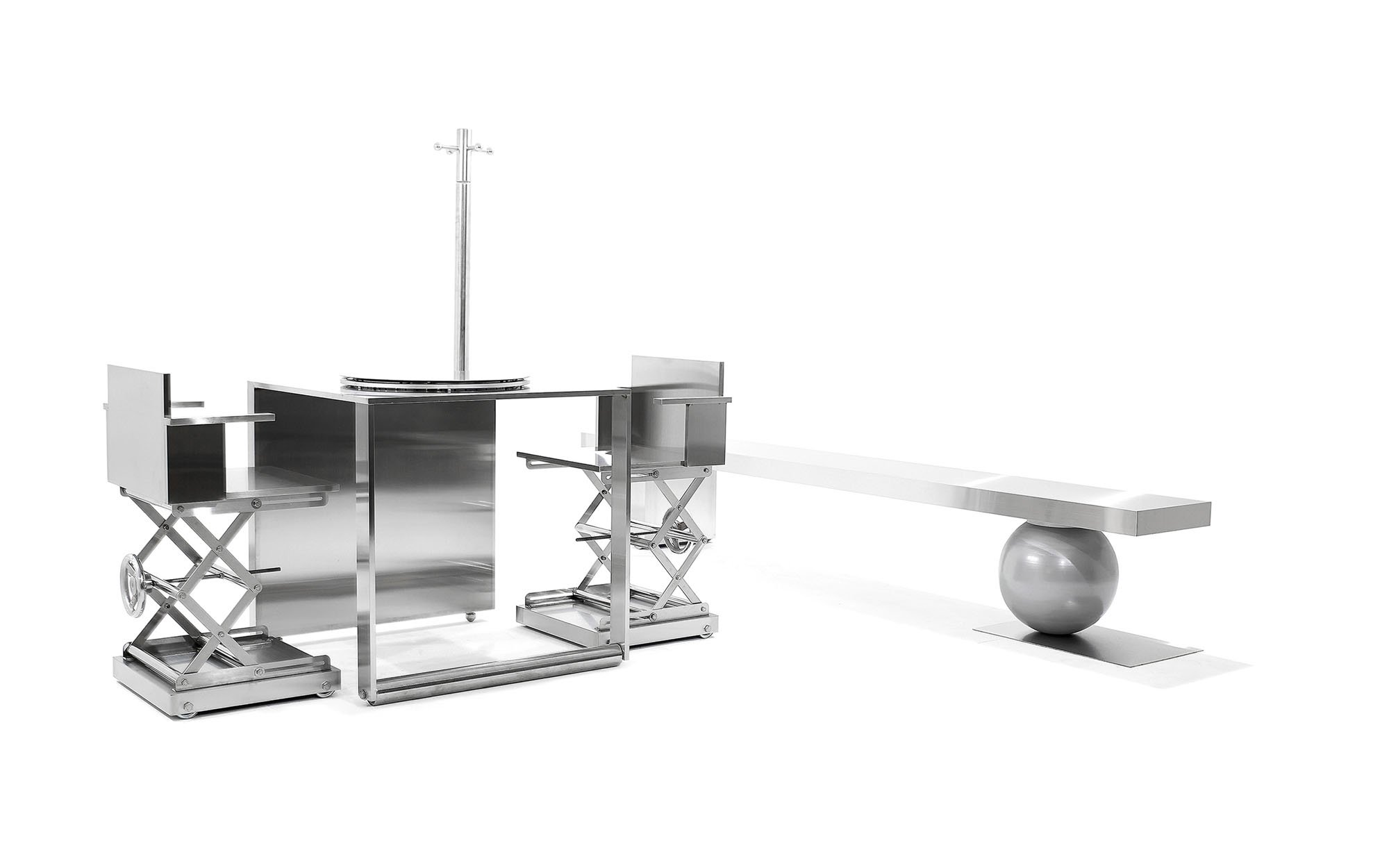

The High-Tech architectural style has also found a revival within furniture and objects. In a more obvious way, the Korean design group niceworkshop’s Affordance Series acts as a love letter to the High-Tech era. The series, created from polished stainless steel, clearly references industry and machinery. The chairs, for example, have industrial lifts rather than legs and roll upon steel wheels. A bench, inspired by an assembly line, sits upon a sphere made with mathematical precision. Bolts and screws are not only exposed but extremely oversize, as joinery and construction act as ornament.

The collection, inspired by the idea of “inducing human behavior and psychology,” pushes its users to perform the tasks of an industrial factory worker on the objects they interact with day to day. “In our daily lives, we unconsciously receive various behavioral or psycho-logical inducements,” explains founder Hyunseog Oh. “The biggest point I wanted to show is the interaction between furniture and people. The series borrows the form of a conveyor belt’s ‘roller’ and an industrial ‘lift’ with clear movements repeated as ‘a device for using furniture.’ ” Recalling Le Corbusier’s idea of homes and furniture as “machines for living,” the collection could be seen as embodying a type of ultramodernity that the High-Tech architects lauded.

Whether in commercial projects or objects, the familiar motifs of the High-Tech Architecture movement, adapted for use on a smaller scale, still attest to a fascination in design with the workings of the machine, even to the point of extending beyond function and into the bliss of ornament.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Products

The Anthros Chair Goes Beyond Ergonomics

A brand-new task chair comes out of decades-long evidence-based research into wheelchair design and the human body.

Projects

Monroe Street Abbey Is an Armature from the Past for the Future

Discover how Jones Studio transformed the ruins of a former Baptist church in Phoenix into a community-centered garden and event venue.