June 30, 2023

What’s the Future of the Workplace? Ask the Workers

Workplace design projects are primarily controlled by clients—i.e., the people who pay for design services.

The dust hasn’t quite settled on the great workforce experiment of the 2020s yet, so there are no easy conclusions to be drawn, except one: If we want to create work conditions that are engaging and meaningful to the workforce, then designers and clients have to change their terms of engagement on workplace design projects.

Step 1:

Acknowledge that the office, home, coffee shop, and coworking space are not the only choices available to employers and employees today. In “Work From Elsewhere” our editorial project manager Lauren Volker lays out four other emerging typologies of spaces designed for work.

Step 2:

Designing for productivity is a dead end—experts can barely agree on what productivity is anyway. Instead, listen to study after study in which workers tell us they value the personal and social dimensions of work the most, and as Architecture Plus Information did in its workplace for Le Truc (“That Return to Office Thing”), think of your project brief as “building a container for relationships.”

Step 3:

Find a higher purpose for workplace design projects where possible. Undertaking a deep community engagement process taught the team at MSR Design that when they were creating Mill 19 (“Postindustrial Innovation”) they were designing not just a place for one group of people to work but also a place of healing for another set who felt as if they had been left behind.

Step 4:

Keep an eye on the ways corporate structures are evolving. Metropolis editor at large Verda Alexander examines one such increasingly popular evolution, the employee-owned company (“When the Workers Become the Bosses”), to understand its implications for design.

Above all, we must avoid even the slightest suggestion that workers are research objects to be studied or reluctant subjects who must be coaxed into the “right” behaviors. Instead, designers, clients, and their workforces have the opportunity to cocreate the working conditions of the next century—the opportunity of a lifetime, if we approach it with humility and respect for one another.

Here are all the stories from the May/June 2023 issue:

Features

At All Scales

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

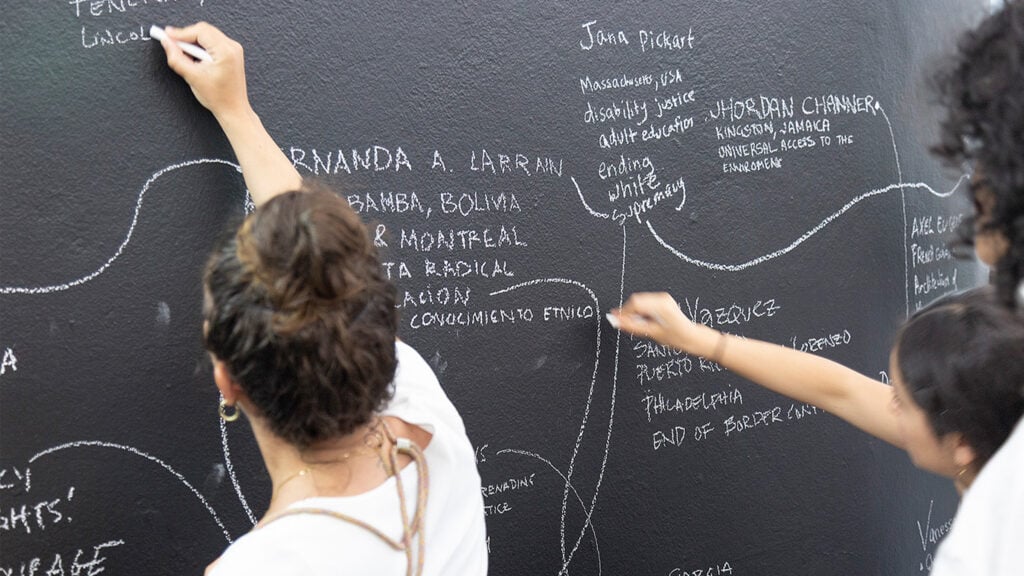

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.